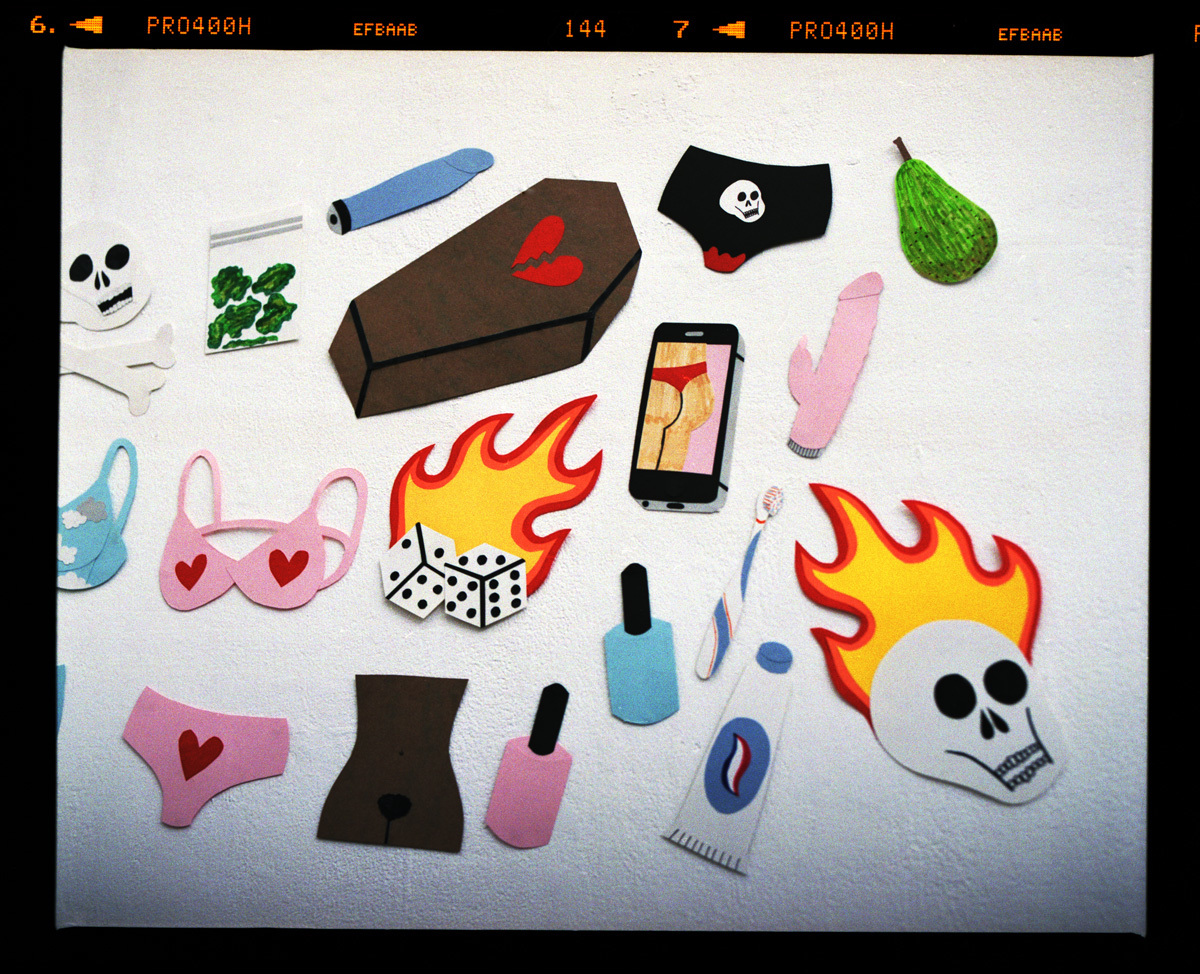

Even a quick glance at Hannah Hill’s embroidery is an evocative experience. Hand-sewn in a hue of eye-catching colors, her art tackles everything from sexual identity to police brutality, gender equality and grime. For her examination of female identity, she collated bras, flowers, lipsticks… objects she doesn’t identify with. For a commission by the Tate on the future of art, Hannah’s vision was that of a multi-cultural, multi-gendered tomorrow. “I’d really like to help change the art world up a bit,” she notes. “I hope more women of color are given bigger and better platforms to showcase their creativity.”

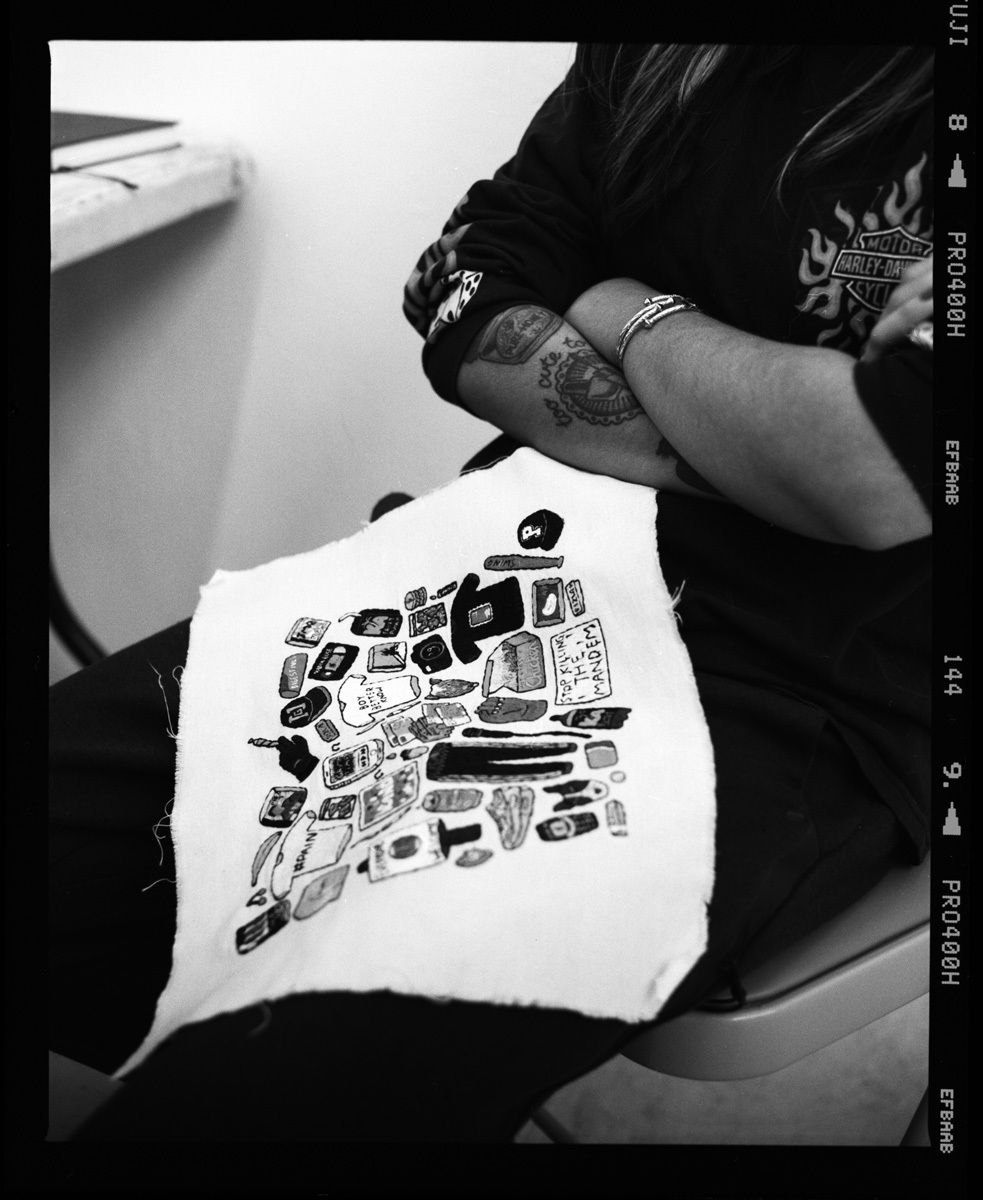

For her piece on grime, Hill, who studies at City & Guilds of London Art School, sewed everything from a packet of digestive biscuits (a ref to JME and Giggs’s cinnamon tea lyric in “Man Don’t Care”) to Dizzee’s Boy In Da Corner artwork to Novelist’s “Stop Killin’ the Mandem” slogan and a carton of KA. Hill’s messages are as extensive as her impact is immediate; contextualizing political sentiment in an entirely different way, her influences may appear sporadic, but laid out on the wall in her south London studio, they make total sense. With a rising social media following and fans such as JME and P Money, i-D meets @hanecdote to discover how embroidery is such a brilliant — yet often undervalued — form of expression.

Hanna describes herself on Instagram as: “22, LDN, Hand embroidery, feminist, stoned art student, mental health awareness and body positivity.”

The North Londoner started sewing at 17: “I’ve always been very artistic, but embroidery drew me in because it essentially wasn’t drawing, painting or sculpture, which I never took to naturally. The more I got into feminism and became obsessed with art and learning about the history of textiles within art, and the feminist empowerment within textiles, the more it interested me. Also my mom’s family is from Guyana via India, so there’s a rich textiles history within my family. I think it’s both artistically and culturally, really. It’s the perfect medium for me to be able to explore parts of my identity like my ethnicity, mental health issues, sexuality, and gender.”

Her mom is quite the creative too: “Both of my parents work for the council but my mom’s really creative; she does a lot of knitting and she’s really good at embroidery. She has helped me with suggesting new embroidery techniques and ideas with my work. I love having her input in my creative process. I’ve always been into art, though I did really shit at secondary school; I only got two GCSEs, so art really has become everything to me.”

Art is very much been a release and a form of expression for Hannah: “I suffer with depression and I was in and out of hospital when I was younger, so art was something for me to both focus on and a way to express myself. Embroidery is really relaxing; not when I’m doing commissions necessarily, but when it’s for me and a project I’m passionate about, it is definitely therapeutic. I’m obsessed with Instagram and social media which is such a fast-paced way of sharing information, so it’s really relaxing to take a step back from that to focus on creating something with my own hands away from a screen. The detail I put into my work packs a punch, the messages or themes are always strong. I think embroidery works well with this because you really have to look close and examine every detail to fully appreciate all the work and meaning behind the motifs.”

Hannah makes art to engage, not exclude: “People often ask me if I like Grayson Perry, I can see why, I like the way he tells stories and helps to make art relatable to people who wouldn’t normally relate to it, which I love. I work with Tate Collective, Tate’s young people’s program, and we make an effort to commission art and put on events that are engaging to young people who wouldn’t typically be an art gallery visitor. We want the events we put on to reflect the amazing diversity in London. I’m all about trying to engage people — art is for everyone!”

With over 34,000 followers on Instagram, Hannah’s sewing is spreading throughout social media: “Some of the grime scene has gotten behind my work — P Money, JME, Tinchy, Frisco, they’ve all been super supportive with comments and retweets, which I really appreciated. I suppose I find it interesting because you have the stereotypes of grime being ‘aggressive’ and ‘masculine’ versus embroidery being very ‘feminine’ and ‘delicate.’ So to have MCs that I respect share it, is crazy. For them to also look as embroidery as art, which they may have never done before, is pretty cool. Two things I love coming together has been such a wicked feeling and makes me really excited about being a creative person right now.”

But she’s not jumping on any sort of ‘grime bandwagon.’ the Londoner has loved the music since fifth grade: “The first time I heard grime was probably 2004 on that Band Aid charity single that Dizzee featured on. I don’t know what happened, but I just clicked with it. That was my first glimpse, but it wasn’t until a couple of years later that I really got into it properly. I really like the storytelling, the politics, their experiences, the confidence, the camaraderie, the wittiness, the raw energy and hype, the lyricism and wordplay. I love lots of things about grime, and flicking through This Is Grime makes me quite emotional because these artists have been captured in stunning photographs, sharing their experiences and they all deserve it. If I’m drawing or sewing, the chances are I’m listening to grime while I’m doing it. It’s something I’ve been thinking about recently, my crossover of grime and visual art. My art is so much more introverted, and I’m introverted, so maybe that’s what draws me to it, the fact it’s so extrovert, mine is a visual medium, theirs is audio. It’s tricky because grime has become really popular in the mainstream in the last couple of years so I don’t want to look like I’m jumping on something just because it’s trendy. I don’t think anyone’s thought that with the piece though; I think people can see it’s genuine. I back everything I put on that piece.”

Hannah is heavily influenced by women: “My influences are women of color artists such as Yayoi Kusama and Faith Ringgold who have faced both racism and sexism in their life, as well as in the art world, yet have created stunning bodies of work about mental illness, slavery, and sexism and still do to this day. I am so influenced by the community of creative babes I follow on Instagram such as @frances_cannon, @monicakimgarza, @cecile.dormeau, @pollynor and @erinmriley. I’m also inspired by beautiful gals, nature, and music.”

Like many young creatives, Hannah isn’t excluded from exploitation: “A big company stole my design; it happened in 2013 and it happened twice recently. But there’s hope; [LA artist] Tuesday Bassen recently had a big case against Zara, which got a lot of press, so that might help change a little bit how big companies interact with artists now. They need to be held accountable. I could talk all day about how frustrating it is that big brands would rather invest in their Legal team than their design team, while hiring shady copy-and-paste graphic designers with no imagination to search the internet for independent artists and makers killing it.”

And is also concerned about how she commercializes her own work without selling it out: “My message is so social and ethical, that really informs my work. But then because I hand-embroider I’d have to charge quite a lot to create individual designs. I don’t want my message to be concerned with, or be complicated by commerce. The most important thing to me is to make art that is meaningful. I’m doing an embroidery workshop with some young girls in South London at the moment, we’re gonna make patches and talk about body positivity and self care, which I think is also valuable, meaningful work.”

Hannah has stuff to say with her art: “I want my art to be important. I want to right some of the wrongs that have been done in art history and in a wider historical context. I want to uplift and celebrate women of color and other marginalized groups because we’ve had to fight so much harder to be recognized. Most of my work stems from being autobiographical, and includes themes which I think are important to raise awareness about, whether that’s mental illness, body standards, endometriosis, rape culture, racism, ableism, transphobia, sexuality, censorship. I hope my work encourages empathy and community and strength.”

Credits

Text Hattie Collins