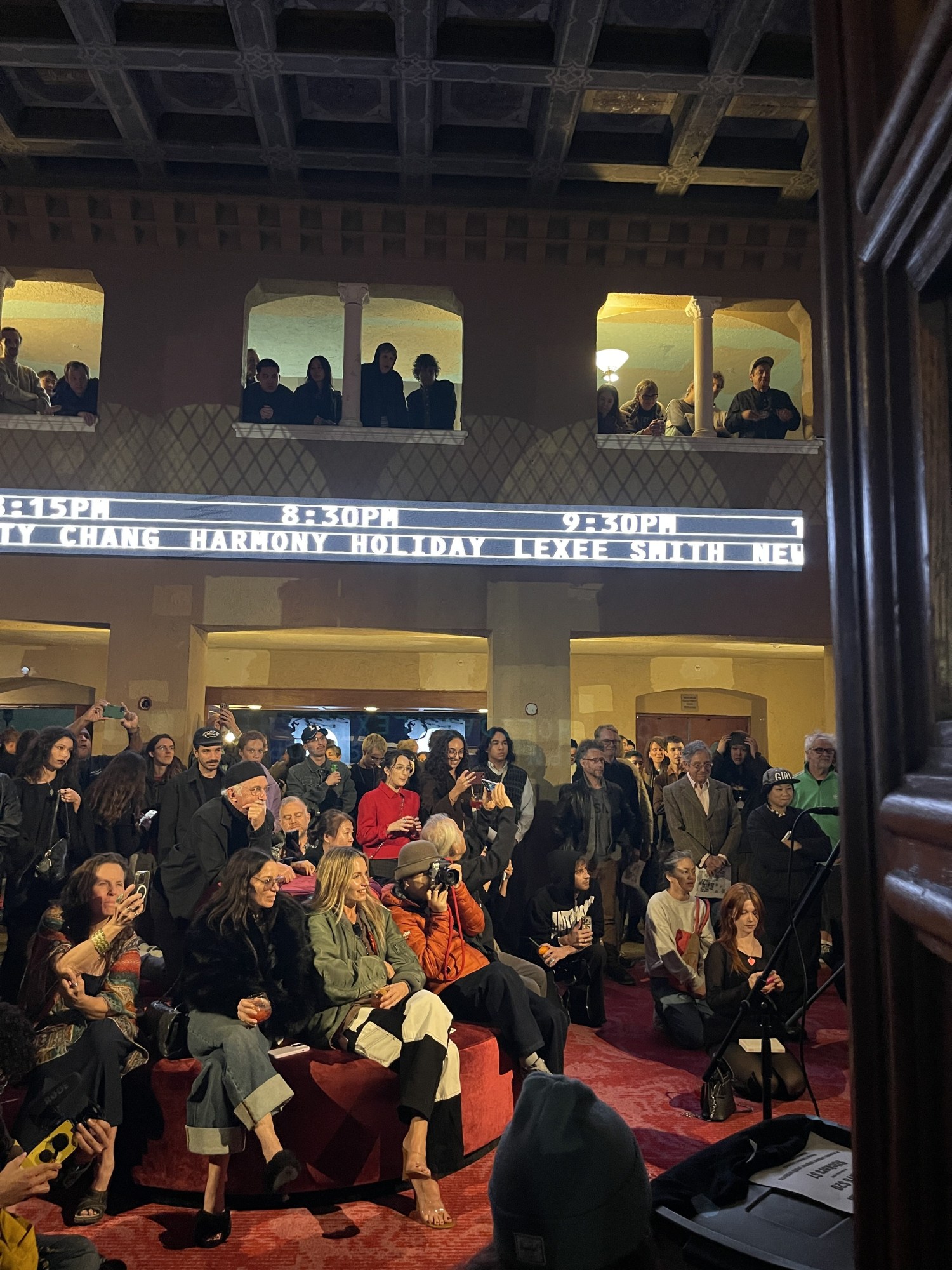

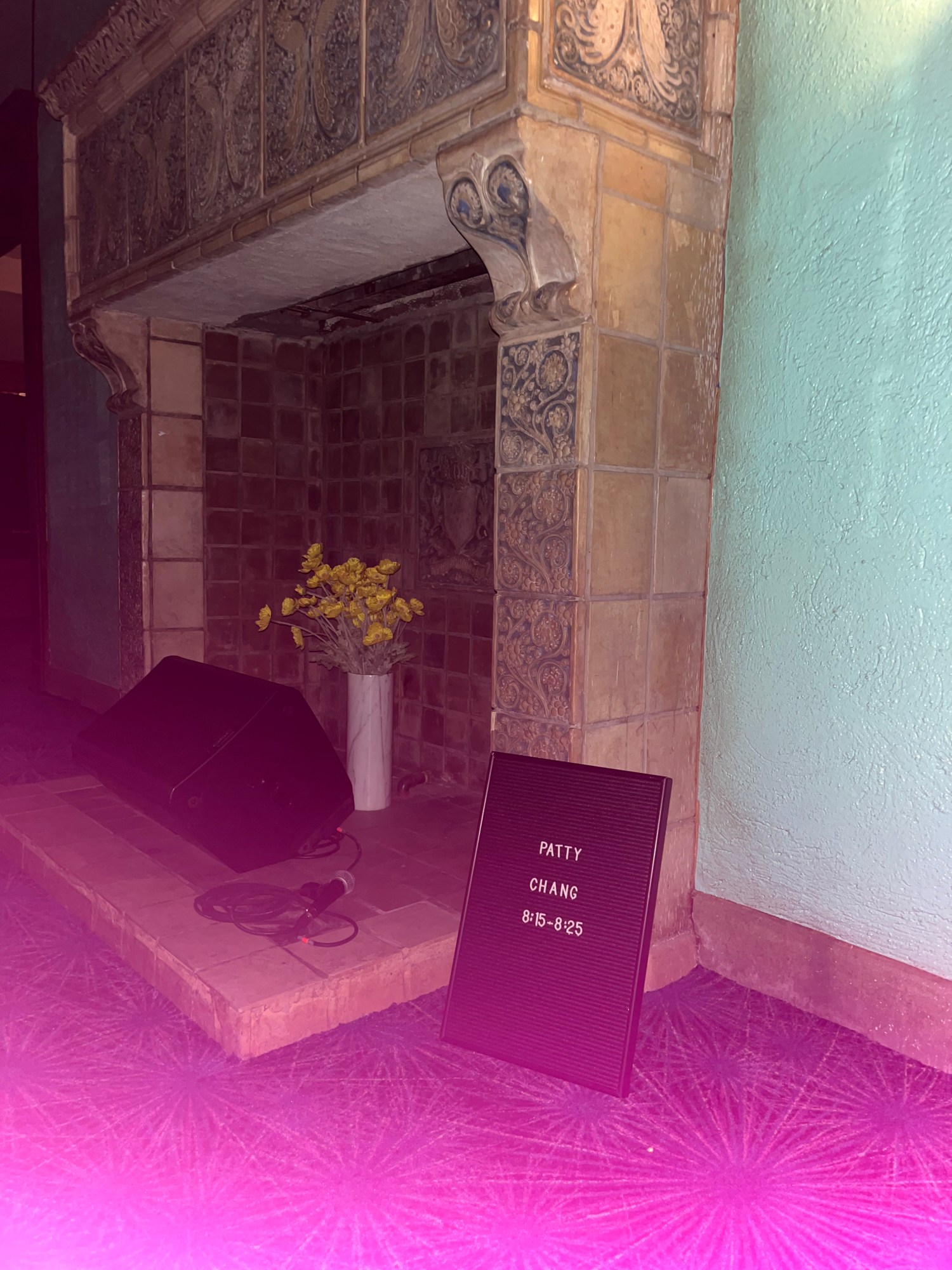

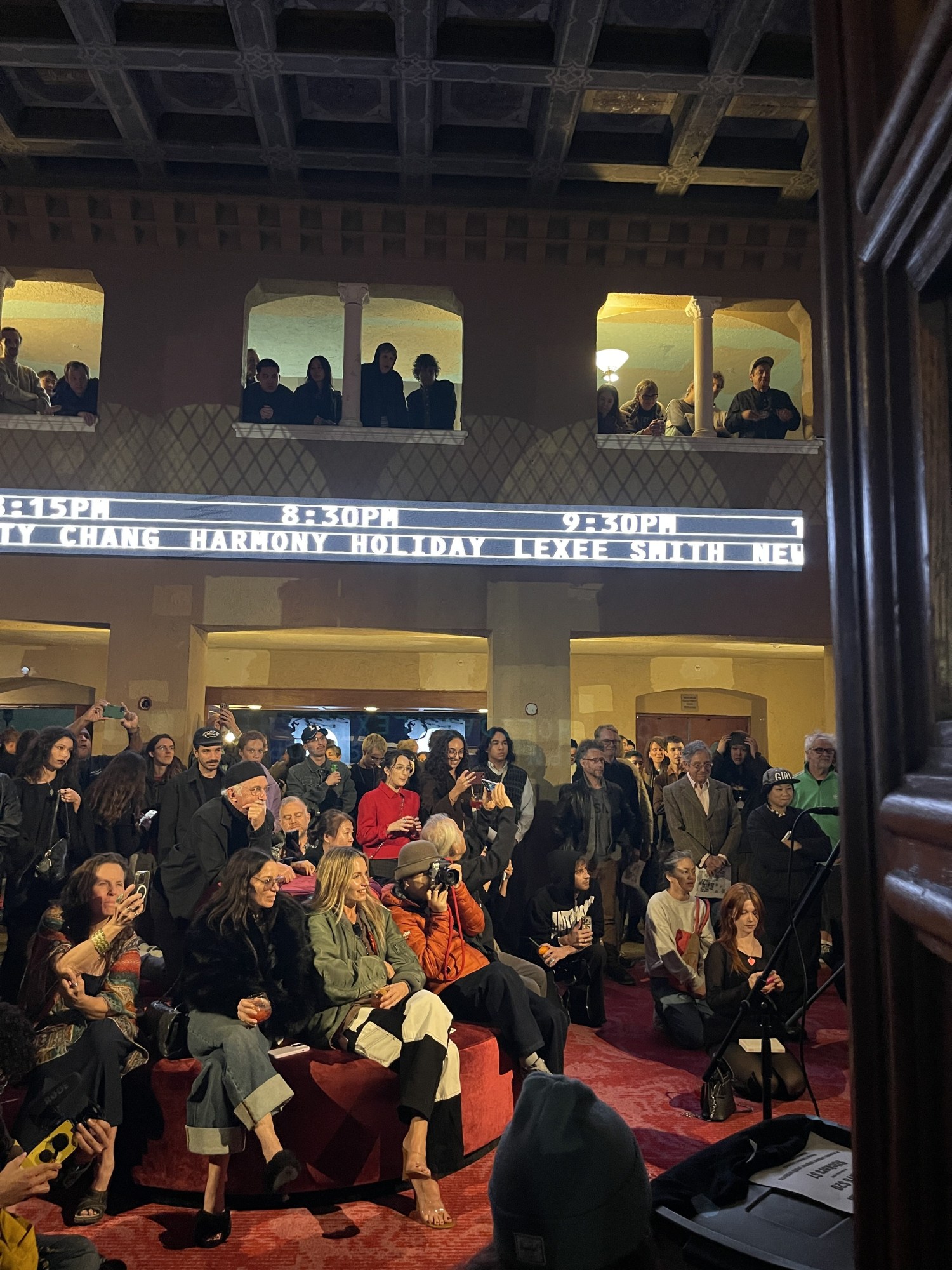

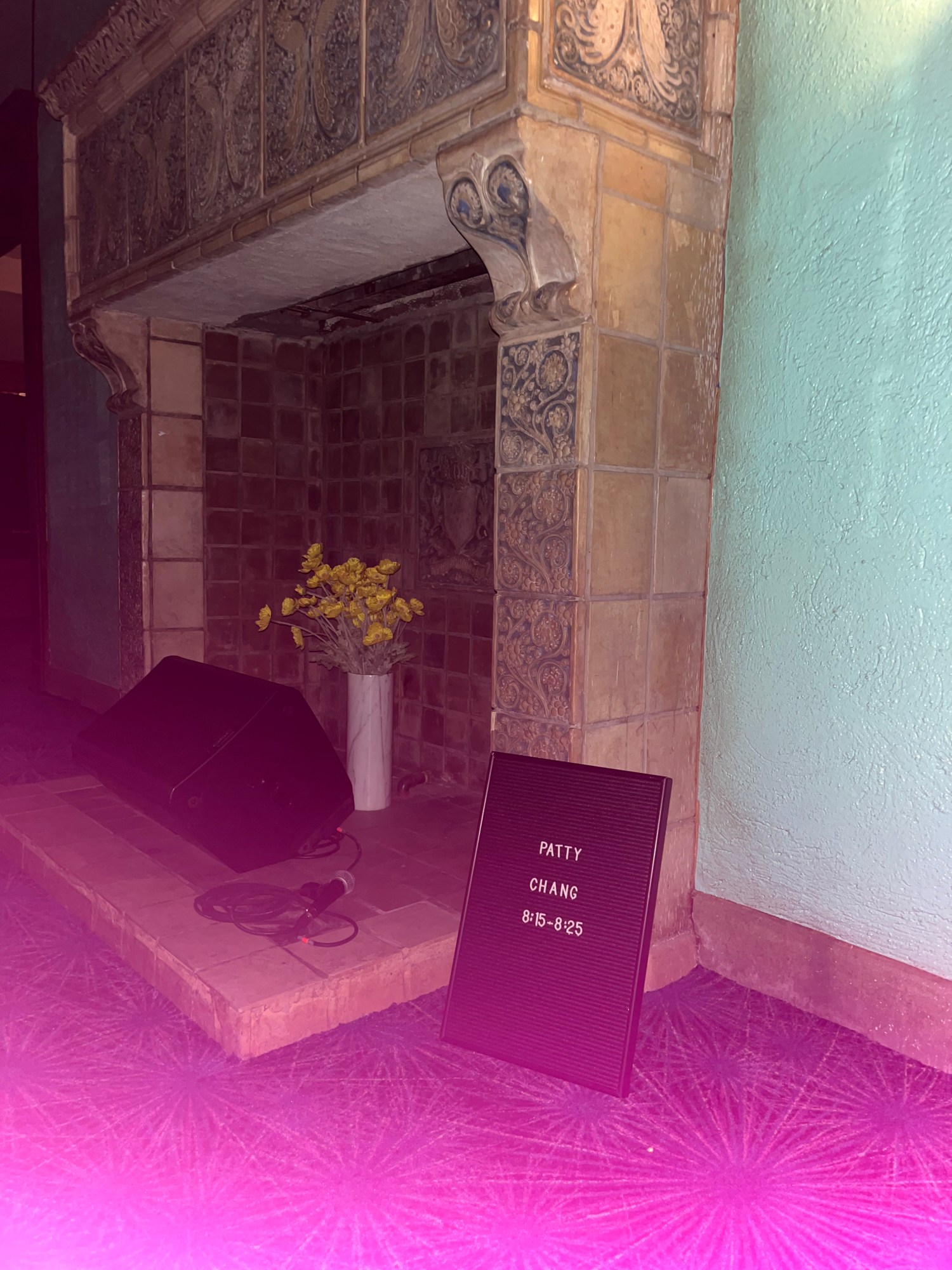

On Sunday night, Hard to Read held a night of performances at the Variety Arts Theater in Downtown Los Angeles. The venue—formerly home to the Friday Morning Club, a clubhouse for women—was an ideal setting for Hard to Read, which has spent the past decade insisting that literature can function less like an institution and more like a live wire.

Founded by writer Fiona Alison Duncan in 2016, shortly after she moved to Los Angeles, Hard to Read started out as a gap-filling exercise. Duncan, who had come from a tightly woven community in New York, found the literary infrastructure in LA comparatively thin.

“I had previously been really enmeshed in a writer’s community, and I remember thinking that LA didn’t have the same kind of literary events or cultural programming as other cities,” she says. She found it enviable how art openings and fashion events treated culture as something to be experienced collectively: “Everything was about celebratory events. I wanted to channel some of that energy and bring it to readings.”

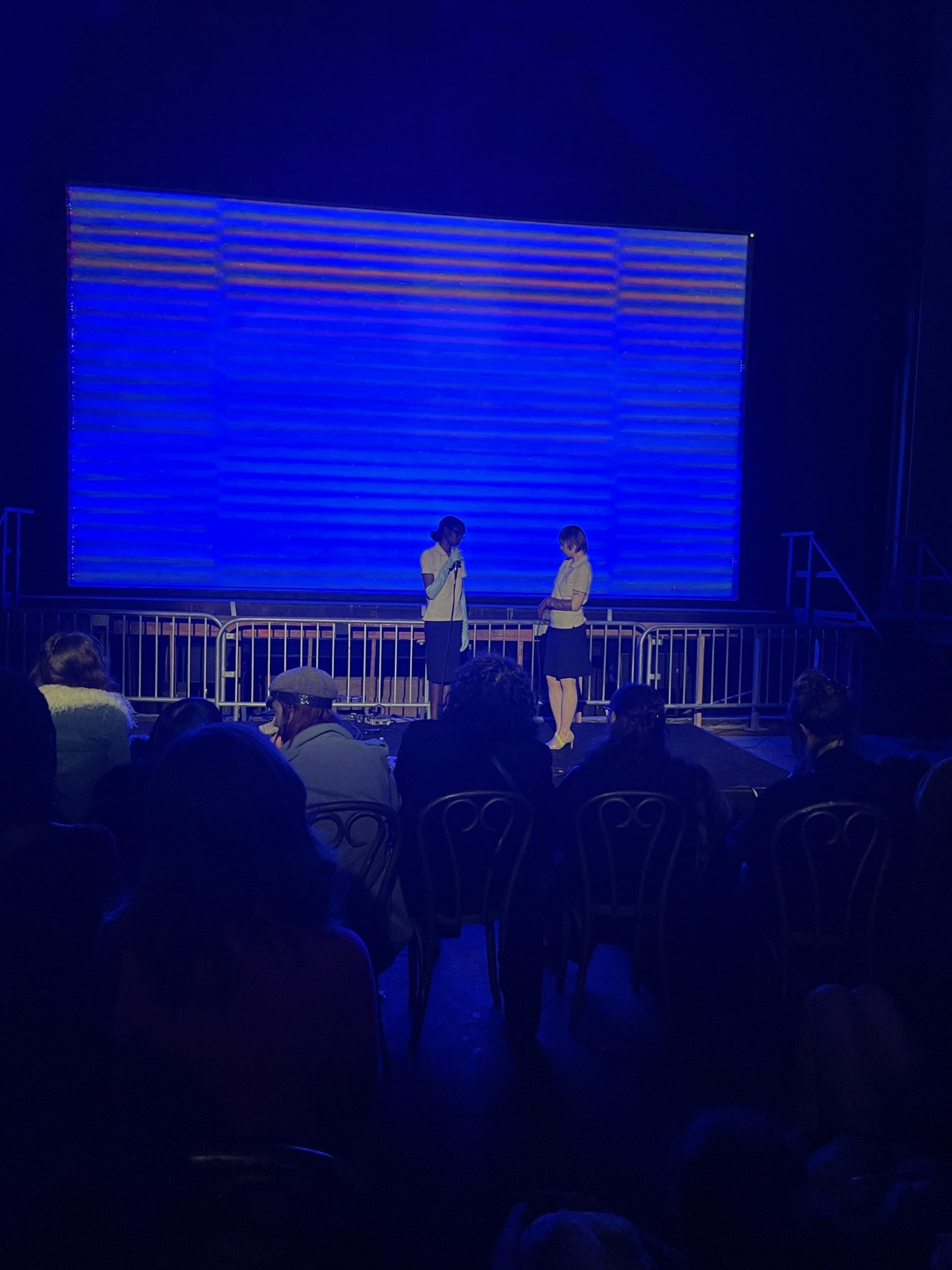

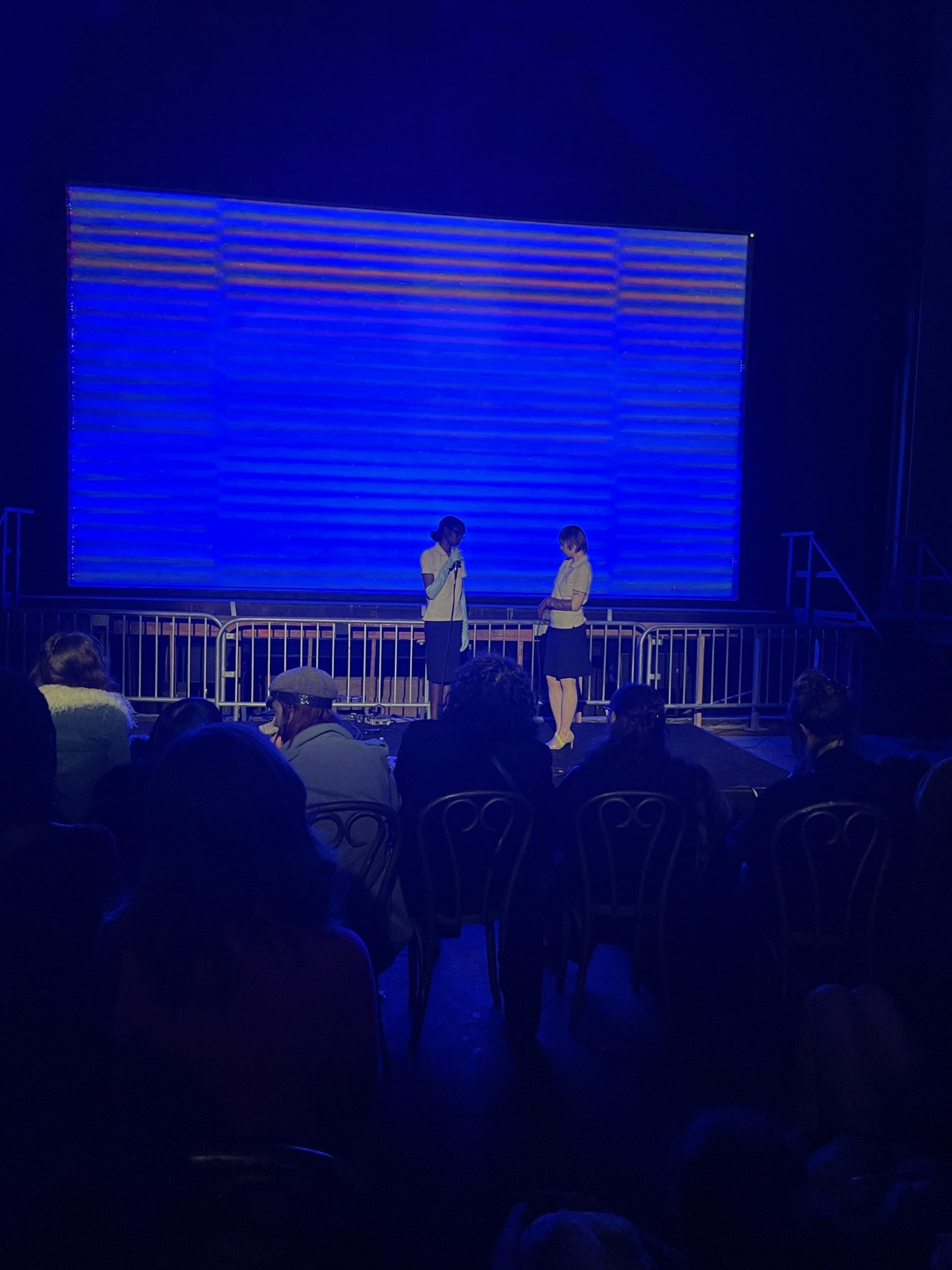

From the outset, Hard to Read offered an alternative to overly serious literary events. “The goal is always to make one that’s not boring,” says Duncan, referring to the bad rep of readings. The performance-heavy program on Sunday underscored that sentiment, with performers including musicians and dancers, such as NEW YORK, and even i-D favorite Lexee Smith. “I’m really excited to have Lexee, because she’s usually in a more commercial choreography or fashion world,” she says. “It’s cool to see it in an art context, because what she’s doing is art—I see her in the lineage of Pina Bausch, Dita von Teese, and Marilyn Monroe. Body Language!”

The event on Sunday took stage inside of “What a Wonderful World: An Audiovisual Poem,” an exhibition curated by Udo Kittelmann for the Julia Stoschek Foundation. Hard to Read has been consistently blurring the boundaries between literature, art, performance, fashion, and activism since the start. Its Instagram bio reads “voice-driven literary social practice,” a tagline just vague enough to indicate that it’s not just another reading series.

“I’m sort of ambivalent about that term [social practice], as it can sound pretentious. It gets a lot of hate in the art world,” she says. “But I like the idea of pushing literary social practice. It just stuck. Anything can fit into that umbrella term. There’s an activist bend to it.”

What distinguishes Hard to Read is its resistance to literary elitism. “I’m really drawn to people’s voices, but I do feel alienated from a lot of the current literary establishment. It’s really stuck in the 20th century in many ways, in the glory days of publishing. Some of the people I meet who are in that world are trying to live out a fantasy of the past.”

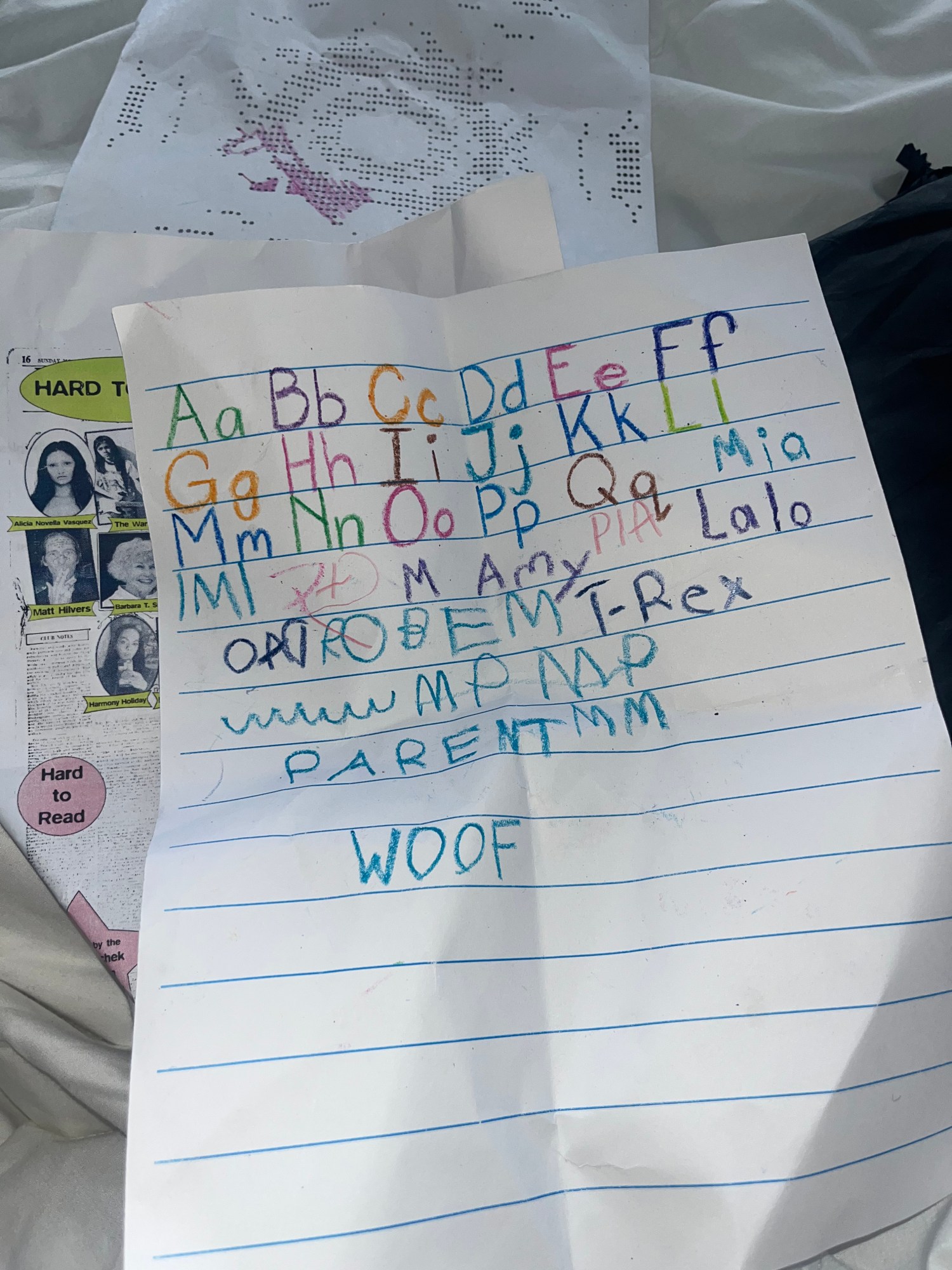

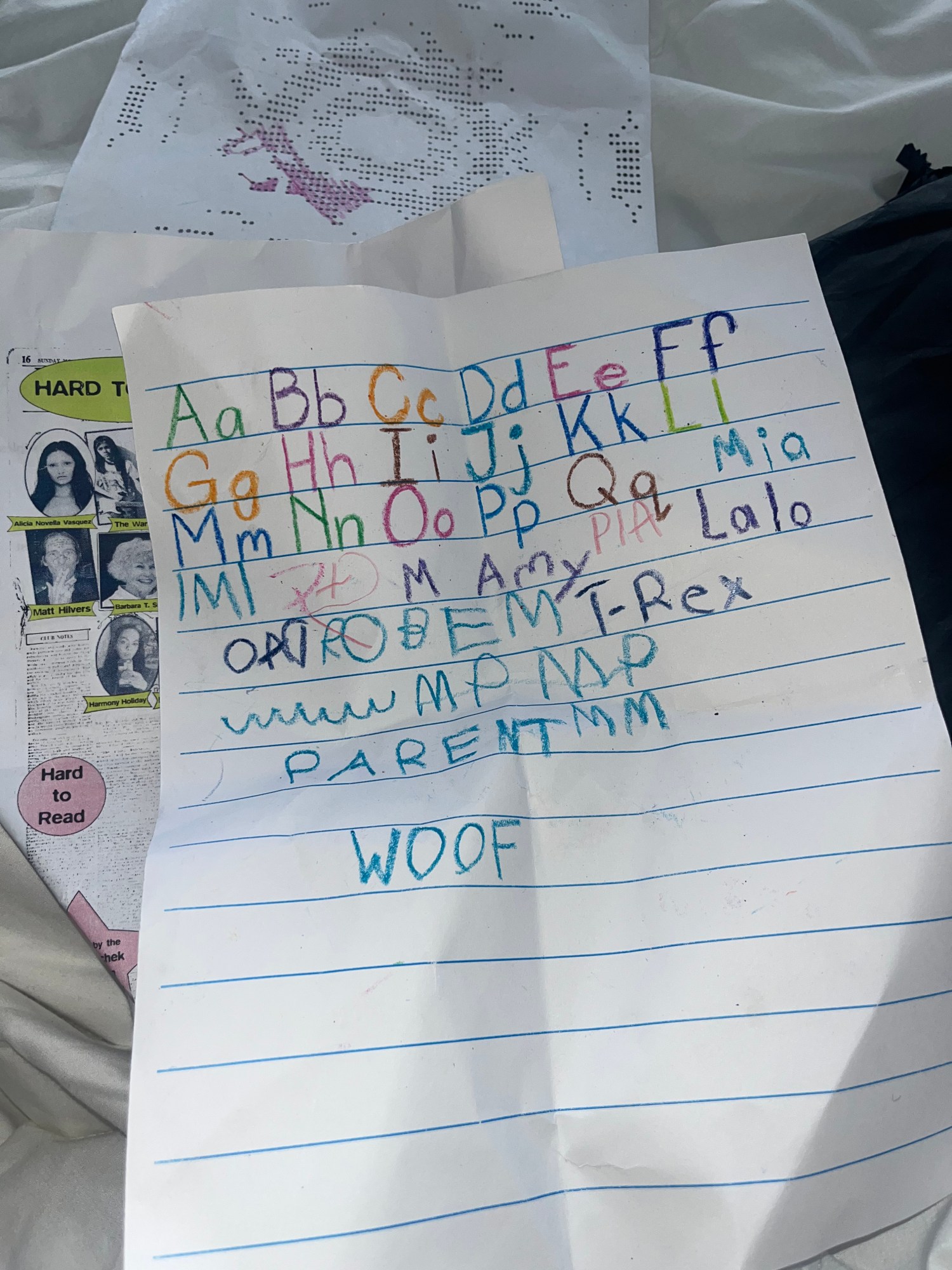

Instead, she’s interested in writing as it unfolds today. Messy, online, and polyvocal. “On the internet you have so many voices that you have to process at any given moment,” she says. Hard to Read reflects that condition by curating speakers whose positions might not be algorithmically “optimized,” or who don’t even identify as writers.

“They’re really good storytellers or observers, or they have a position or an experience that is really interesting to relay,” she explains. “And sometimes they write their first thing ever for it.” The selection of readers often reflects who Duncan admires; she describes herself simply as “a fan.” Attraction, she says, comes down to voice—how someone sounds on the page and in the room. “I am also, ‘proudly woke,’ and that’s part of it too,” she jokes half-playfully, acknowledging how derogatory that term has become. What she looks for instead are people with “standards, morals, and ethics,” even if what they deliver is everyday or goofy rather than overtly polemical.

For Duncan, writing isn’t something sacred. “I don’t think writing or language is pretentious at all. It’s the most common thing—we all use it. Anyone can write—whether you can write well or not is a very different thing,” she adds, laughing. “And that’s just about intentionality and practice.”

“I think people are afraid of books and writing and literature because it’s shoved down our throats in a school context,” she says. She’s quick to point out that learning no longer happens exclusively through books: “Look at ‘YouTube University’ or ‘Tumblr University.’ I don’t think books and writing should be pretentious. I love reading books and challenging texts, but I also love reading my friends’ text messages. It’s about occupying both.”

Duncan eventually realized she was operating more within the art world than literary circles. “The art world has just been a place where experimentation is more supported financially,” she says. But even that support feels precarious now: Funding crises, creeping conservatism, a perceived disengagement from younger generations and collectors.

Over the years, Hard to Read has staged events in unconventional spaces—from a mall in New York’s Chinatown to luxury hotels. The idea first clicked on a walk to the Los Angeles Public Library, when Duncan noticed The Standard hotel beside it and realized it would be a good space for programming. What started as a random thought has since expanded into hundreds of events spanning a decade.

One of her favorite events includes the consent-focused program she organized with Pornhub. This was part of Pillow Talk, a Hard to Read spin-off series which she admits began with a slightly ulterior motive: “That was mostly a con. I was already hosting out of hotels, and I really wanted to be in the rooms, because I’m obsessed with hotel rooms.” Instead of readings, the series invites people to have difficult conversations in a soft environment. “I think hosting the talks is harder than hosting the readings. You have to get people to ‘real talk,’ and trust themselves, the audience, and the context, rather than have a prepared thing which is more about control.”

As Hard to Read gained visibility, reading series across New York and Los Angeles began to multiply. Similar to how Chappel Roan introduced herself as “your favorite artist’s favorite artist” at Coachella 2024, Hard To Read is probably your favorite reading’s favorite reading.

“I’m weirdly competitive in my service-mindedness,” she says. “If everybody’s doing this thing, I’m not gonna do this thing anymore.” At least two or three series, she notes, were directly inspired by Hard to Read. While she welcomes the collective impulse—“it helps us balance this internet addled-ness”—she wishes people would replicate her format of dialogue and talks instead.

It’s now been ten years since the start of Hard to Read. “Time goes by so fast, it’s shocking,” she says. In the early years, she sometimes staged 20 to 30 events annually, propelled by what she now recognizes as a kind of youthful grandiosity. “I think I used to believe that it could really change things to do this. And I still think things can be changed, but in a much smaller way. Maybe from just one person to another.”