The Helmut Lang exhibition opened in December at MAK, Vienna’s Museum of Applied Arts. It is, according to the museum, “the first comprehensive exhibition of Helmut Lang’s oeuvre”—a milestone that feels both exciting and a little overdue for a designer who fundamentally reshaped 1990s fashion. There are many Helmut Lang fans out there who’ve been hoping for something like this. And then there’s me. As a terminally online, self-appointed “expert” on the subject, I have a lot to say about what such an exhibition could look like. My interest in the label began when I bought my first Helmut Lang piece, a leather jacket, about 15 years ago. Since then, I somehow ended up creating ENDYMA, a fashion archive that now includes the largest collection of vintage Helmut Lang in the world.

So yes, I did feel a little FOMO when I realized that this exhibition was planned without our archive’s involvement. The second sentence of the museum’s press release twisted the knife even further: “[MAK is] the largest and only official public archive dedicated to [Lang’s] legacy.” It read like a pointed diss, reducing our archival work to unauthorized hoarding, and not even the largest at that.

I’ll admit it. The moment I landed in Vienna, my first mission (embarrassingly petty) was to settle who really has the largest Helmut Lang collection. MAK’s catalog lists 1,650 garments, all donated by the designer himself. ENDYMA’s sits at 3,201. So how did the museum’s archive end up being “the largest”? By counting Polaroids, advertisement proofs, handwritten notes, and administrative supplies that were recently cataloged for this exhibition, their tally shot past ten thousand. All crucial for an institutional archive, no doubt, but a collection of a fashion designer’s work is typically measured in fashion objects. So while our archive will forever be cursed to be an unofficial one, I could sleep easy knowing ENDYMA is still the largest collection of Helmut Lang clothing. Great.

Helmut Lang was one of the most influential fashion labels of the 1990s, shaping an entire generation’s definition of cool. He was a champion of 1990s post-grunge eclecticism, finding beauty in places that were often overlooked. His designs often involved subtle gestures of casual dressing: the strap of a camisole dress gently slipping off one’s shoulder, or the way a T-shirt breaks after years of wear. These ideas were unwaveringly developed into a body of work that is seductively pure in concept yet resistant to categorization. Underwear, tailoring, gym clothes, military surplus, eveningwear: categories that were seen as distinct and incongruent in the 1990s, brought together into what we now recognize as contemporary urban style.

The thing I noticed upon entering MAK was its ornate Austro-Hungarian splendor; this is clearly a place where only the finest stuff is kept. The Helmut Lang exhibition in the Lower Exhibition Hall offers a pleasant break from all the stucco. The gigantic space channels the white-cube atmosphere of Lang’s runways and workspaces, with video displays offering the only touch of color. Large-scale reconstructions of the dark metal garment displays from his NYC boutique define the space. Unfortunately, there are no garments in any of them.

Curated by Marlies Wirth, a Vienna-based art historian and curator specializing in contemporary digital culture with no prior focus on fashion, the exhibition takes a somewhat unconventional approach. In Wirth’s view, the story to be told about the most influential fashion designer of the 1990s is fundamentally about brand storytelling. There must have been no more than twenty-five pieces of clothing on display in the entire show, and it’s huge. Instead, the exhibition primarily relies on printed matter, images, and video to convey not what the brand sold, but how it shaped its image.

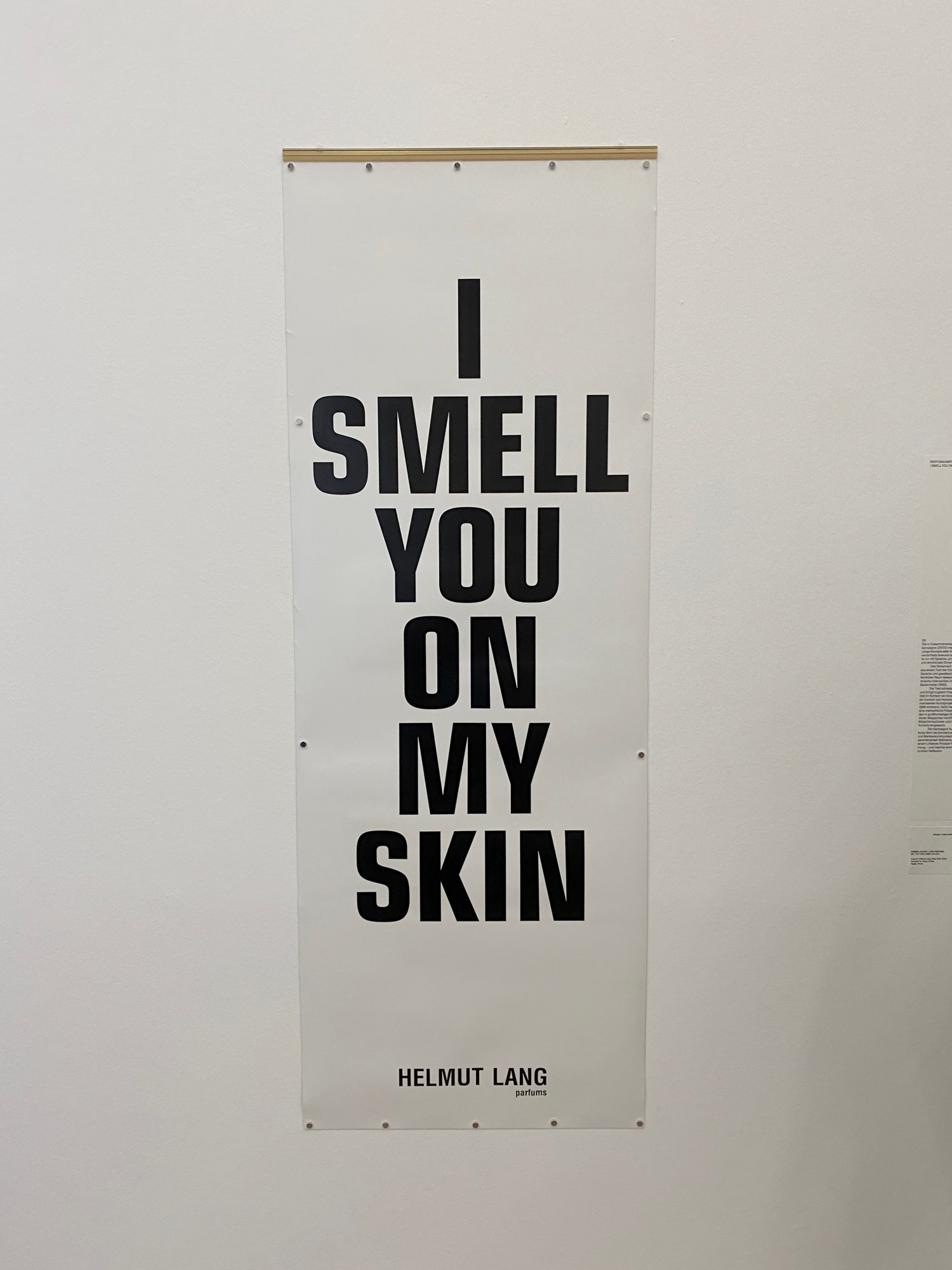

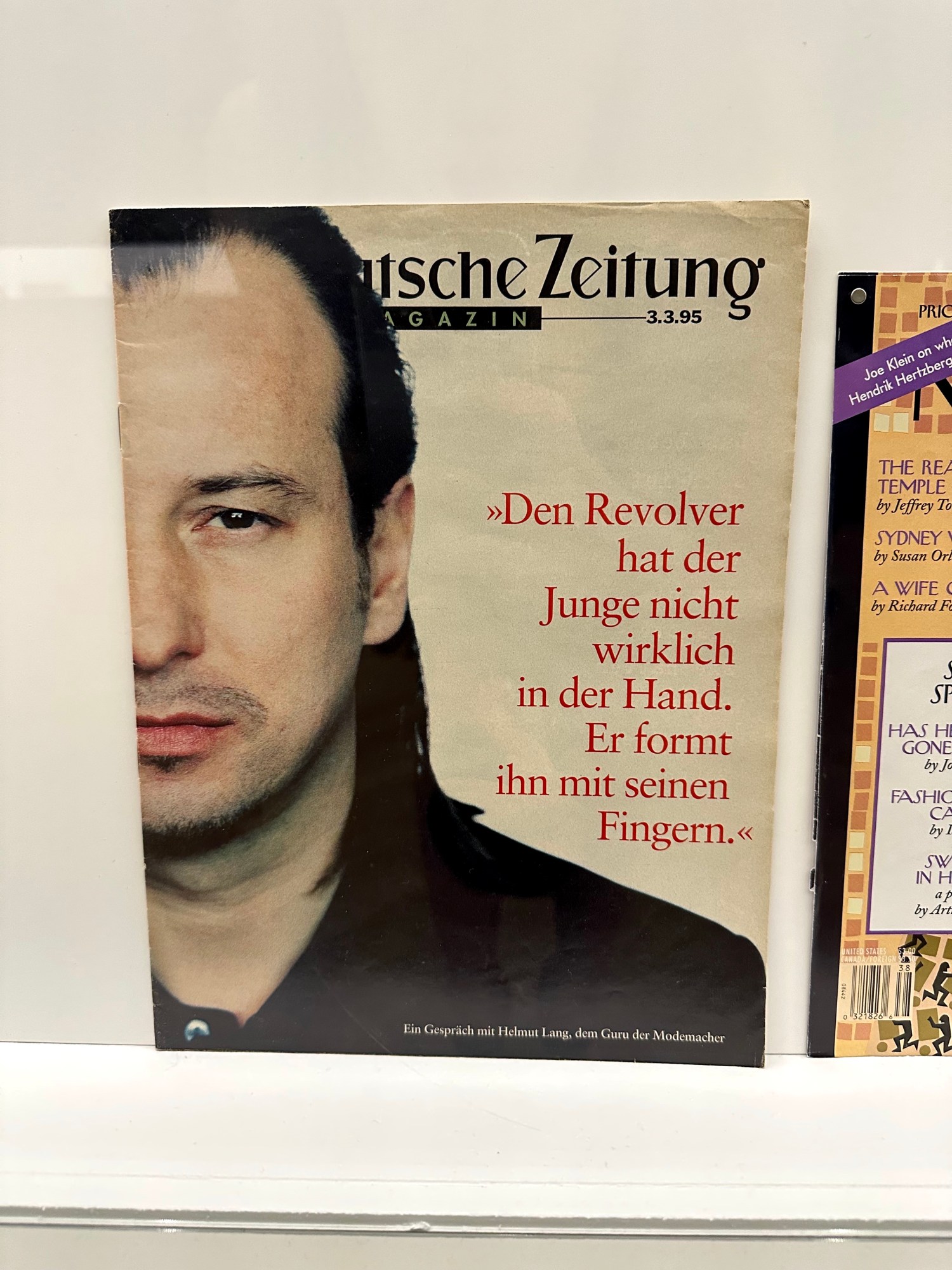

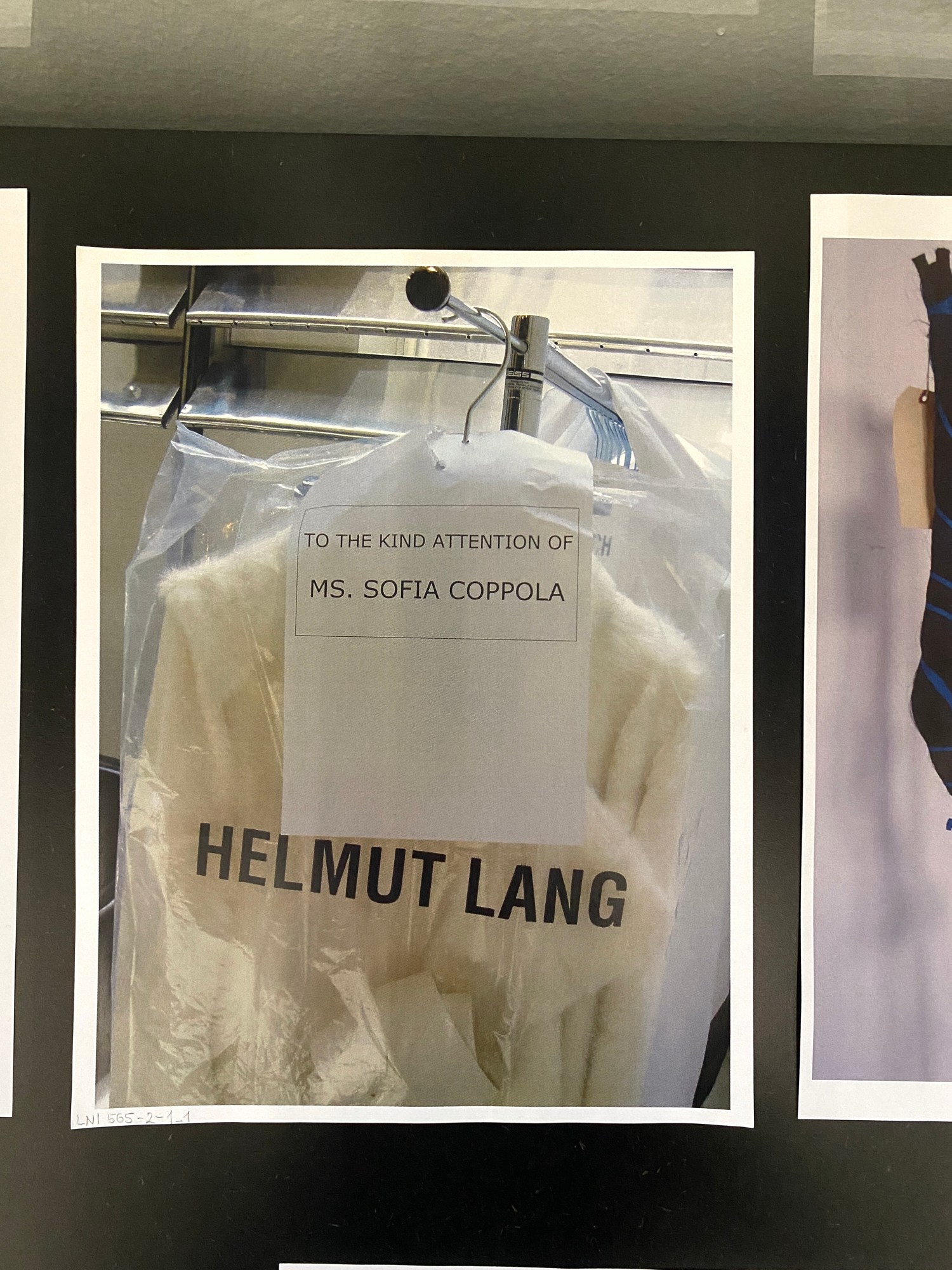

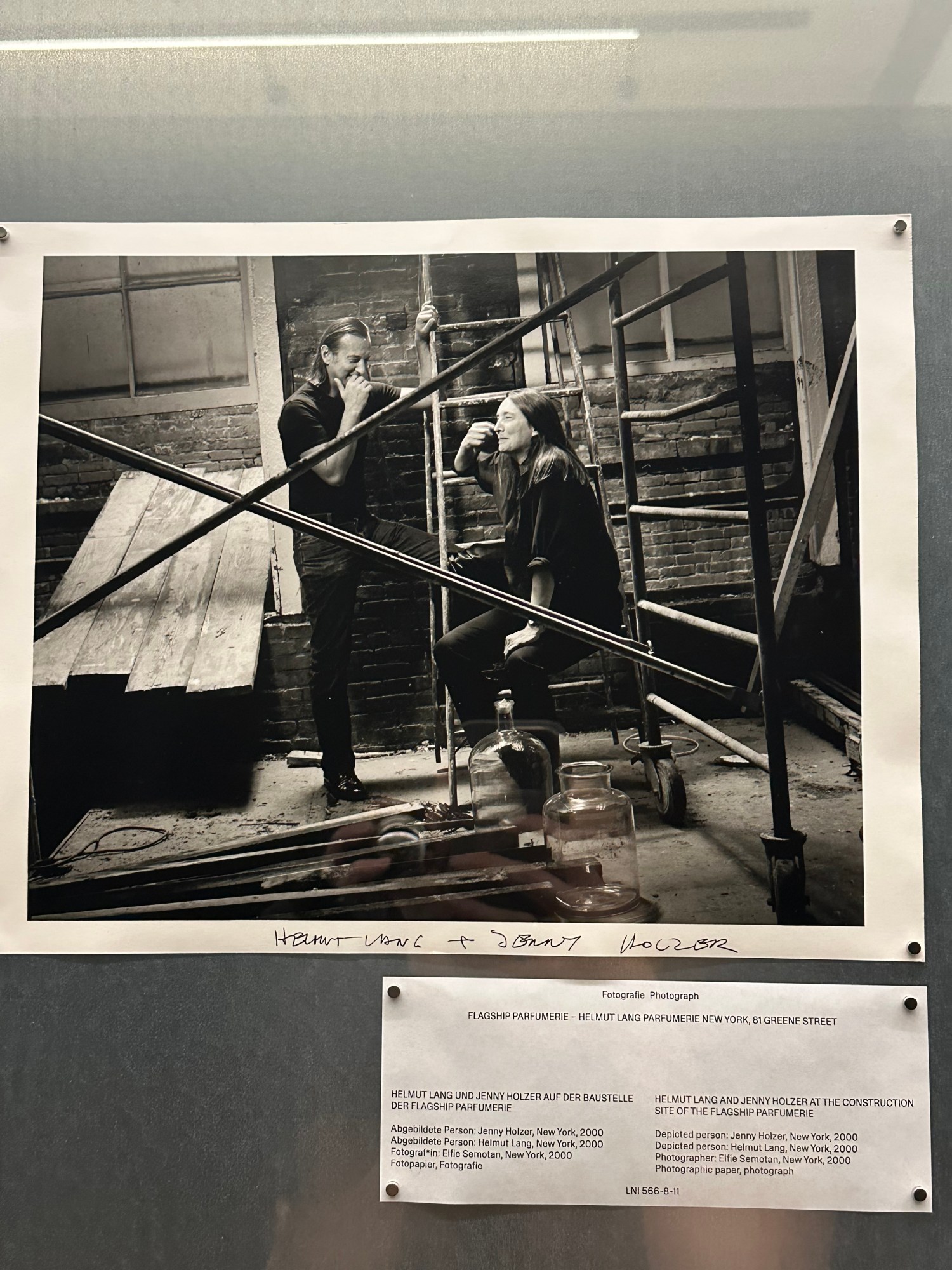

Wirth’s viewpoint has merit. Helmut Lang’s approach to marketing was legendary, effectively rewriting the playbook of fashion advertising. The campaigns communicated the essence of the clothes without revealing them. Instead, the designer collaborated with acclaimed artists (among them Louise Bourgeois, Robert Mapplethorpe, and Jenny Holzer) to create stark visuals that brilliantly challenged conventions around the function, placement, and messaging of fashion advertising. Helmut Lang stores followed, with gallery-like interiors that broke many rules regarding the merchandising and display of products, often showcasing artworks in their windows instead. Lang took great risks with his brand-building strategy, and his decisions remain valuable both for their artistic merit and their lasting influence on contemporary creatives.

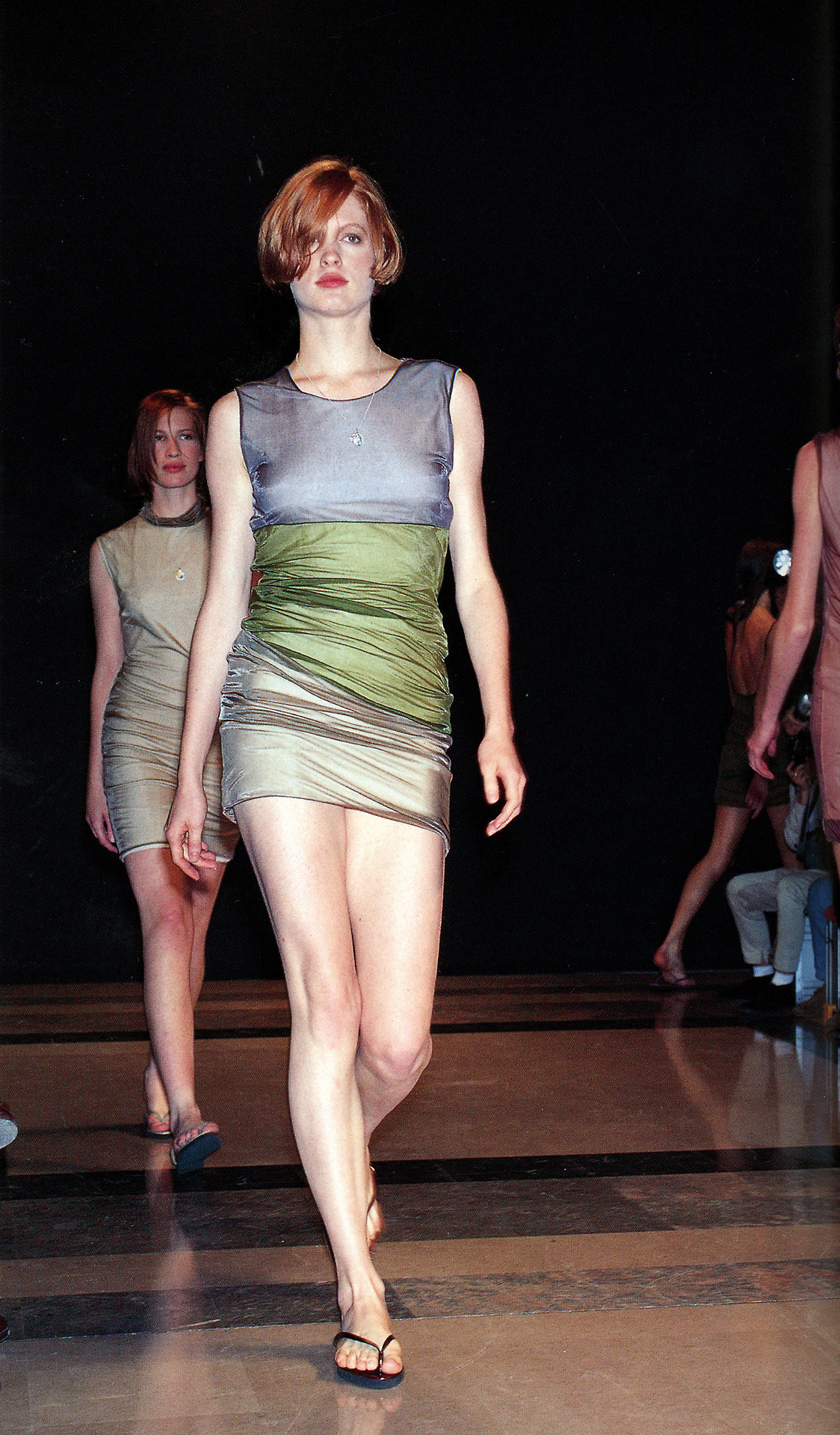

With that said, reducing Helmut Lang to its visual communication inevitably neglects the interesting and well-designed clothing. But what’s so special about it? Defining Lang’s designs is tricky; the range was as diverse as it was unpredictable. Weightless, translucent dresses in delicate layers that looked both intimate and otherworldly. Military parkas in aged fabrics with obscure utilitarian details, both functional and unexpectedly poetic. Suits formal enough to pass as anonymous, invisible to anyone not paying attention, and the opposite of today’s gratuitously designed tailoring. Jeans that redefined classic denim as high fashion years before “designer denim” became a thing. Tanks and strap tops so resolutely proportioned they achieve something close to classical perfection.

Interestingly, these clothes did more than define 1990s style. Kids still love to wear and obsess over Helmut Lang designs today. Don’t take my word for it: a quick search on any online marketplace reveals jackets, coats, and jeans selling for substantial sums, often multiple times higher than their original 1990s retail prices.

The absence of clothes was most felt in the exhibition’s vast central room, a nearly empty white space whose floor was printed with the seating chart of a Helmut Lang runway. I assume the intention here was to evoke the atmosphere of Lang’s “Séance de Travail” runways, unconventional for their absence of a catwalk, speed, and lack of bling. A large video display played a loop of Helmut Lang shows from the 1990s. Beyond the display and floor graphic, which was also reproduced on a wall, the space was strikingly devoid of exhibits, except for sculptures made by Lang after he quit fashion. The stick-shaped structures, titled “Make It Hard,” were made from Helmut Lang garments from the designer’s personal archive that were shredded, dipped in resin, and painted. The gesture of destruction and rebirth they convey is powerful but, having spent significant time and resources restoring such garments in our archive, I had mixed feelings.

An adjacent room dedicated to Helmut Lang’s idiosyncratic “accessoire-vêtements” (harness-like pieces from his final years as a designer) was somewhat underwhelming. For one, some pieces needed ironing. More importantly, by displaying only clothing that primarily expresses abstraction while severing connections to the everyday shapes Lang brought to fashion, the exhibition frames his output within artistic practice rather than fashion design. This conveniently elevates his work “above” the mundane realities of the industry, defying comparison and, therefore, criticism. Might visitors benefit from knowing that these final collections were commercially unsuccessful and somewhat misunderstood? That many of the label’s loyal customers, primarily seeking wearable clothing, felt the designs had gone too far?

A smaller, darker room screened all the runways from 1988 to 2005. This space, with more than thirty tightly arranged videos playing simultaneously, felt like a special kind of split-screen torture. And yet, the shows remain brilliant. Fast-paced models, both famous faces and Lang’s distinctive Viennese entourage, wearing simple, even archetypal clothes. Yet there is a strong sense of rare, cutting-edge creativity in their outfits. This is thanks not only to Lang’s vision but also to the late Melanie Ward, a brilliant stylist and his closest collaborator for over a decade. The exhibition’s failure to properly acknowledge Ward’s involvement, beyond a couple of reproduced show credits here and there, was a letdown.

Beyond Ward, the exhibition barely acknowledged the extensive team that built the brand. Stephen Wong, the art director responsible for much of the brand’s celebrated graphic work and advertising, received no mention. Nor did Kostas Murkudis, Lang’s first assistant from 1986 to 1993, who helped define the label’s design language and later became a celebrated designer in his own right. Christian Niessen, who succeeded Murkudis and eventually became head of the design studio, was also absent from the narrative. The same goes for the many other collaborators who shaped what we recognize as “Helmut Lang.” This is not to say that all of Lang’s various employees and contractors should be credited no matter what, but the total omission of their involvement risks depicting Lang as the singular mastermind responsible for everything, which is probably not the case in any fashion label.

Interestingly, the curation had no trouble crediting collaborations when they were with established artists. By centering Lang as the sole creative force behind all things fashion while highlighting his artistic collaborations, the exhibition presents an incomplete narrative that perhaps serves the interests of a living artist more than it illuminates the collaborative, and messy, reality of fashion design. It also draws a clear line between whose labor is considered worthy of recognition.

The pressing question that emerged was whose story this exhibition was telling. Was Wirth curating the historical archive of a fashion label, or collaborating with a living artist on an exhibition shaped by his current perspectives? Lang’s transition from fashion to visual art may be at odds with his design past, and a “comprehensive” retrospective focused on marketing and imagery rather than clothing sidesteps certain complexities. This may reflect a curatorial choice, or it may reflect Lang’s own interests in how his fashion legacy is portrayed.

In my view, the exhibition succeeded on its own terms, outlining Lang’s impact as a marketing pioneer and highly influential visual communicator. It is worth the trip to Vienna for that alone. But this narrow focus came at a cost. In today’s content-saturated hellscape, turning a fashion exhibition into screens and brand imagery deprives visitors of the opportunity to appreciate the real-world impact of Lang’s clothes. His work wasn’t just ingenious advertising; it solved real problems through design that felt pragmatic, dignified, and deeply human-centered. As Sarah Mower wrote over 20 years ago, “grown women used to cry over how his pants, tanks, jackets, and coats offered such coolly simple solutions for everyday dressing.”

Perhaps what’s most disappointing is how close this show came to being brilliant. MAK has the institutional authority, a sizable archive, and the resources to tell a complete story. What this exhibition lacked was the willingness to get messy: to explore the intricate layers of clothing, acknowledge the many hands that shaped Helmut Lang, and trust that fashion design is interesting enough on its own terms. The clothes that moved people in the 1990s, that kids still love to wear today, and that changed how an entire generation thought about getting dressed deserved to be there. Some of these garments did appear on opening night, not in the exhibition’s displays but worn by visitors, quietly reminding us of the label’s enduring relevance across generations.