There is no luxury house on the planet more shrouded in secrecy than Hermès. Just saying the word feels somewhat luxurious — it’s pronounced “air-mez”, though French people often add a flourish of throaty rasp. By now, you will surely be familiar with the folklore surrounding the brand. Even if you have the money, you can’t simply buy Hermès bags — there are protocols, rules, much of which is the subject of #Hermès-related content on TikTok, which has currently amassed more than 3 billion views on the platform.

The 185-year-old house’s products range from homeware beloved by Kris Jenner, to equestrian saddlery used by Olympians, silk scarves worn by the late Queen, and of course, the candy-store assortment of Hermès bags worth more than their weight in gold – a familiar sight in the walk-in wardrobes of Hollywood stars and couture clients. Demand often outstrips supply, simply because everything is handmade and intentionally limited in in its production.

Today, the brand is often associated with status and hard-to-get luxury, but Hermès has always stood for discreet, patrician taste rooted in equestrian craftsmanship. As far back as 1940, The New York Times reported: “It has been said of Hermès, that it is perhaps the only establishment in the world in which one cannot buy a single article that is not in perfect taste.”

Paramount to the house’s reputation is its unwavering quality. With an emphasis on the handmade, with many of its products still entirely made in France, it implements a fassidious quality control protocol that renders products with even the slightest defect – a minuscule mark on a scarf, a stitch amiss or a blink-and-you’ll-miss-it scratch on buffed calfskin, a tiny bubble in a piece of crystal – unfit for the shop floor. If it isn’t perfect, it won’t make the cut — but instead of being discarded, it will be offered to petit h, the division of the house that upcycles discarded offcuts and defected materials into imaginative yet functional objects.

Long before sustainability and upcycling were part of the fashion lexicon, Hermès launched petit h in 2010 to create “a playful dialogue around sustainability and reinvention, object creation and the reuse of materials,” according to Godefroy de Virieu, the ruggedly handsome product designer and artistic director of petit h. He was hired by Pascale Mussard – a sixth generation descendant of the house’s founder, Thierry Hermès – who conceived of petit h as a means of developing new products from what was left of the old ones, inspired by her childhood collecting scraps from the cutting-room floor to create her own toys. “When Hermès started this project, it was not at all to be just a communication point,” he urges. “It’s because it’s common sense and it’s in the roots of Hermès to keep these materials that are beautiful to transform them in new objects.”

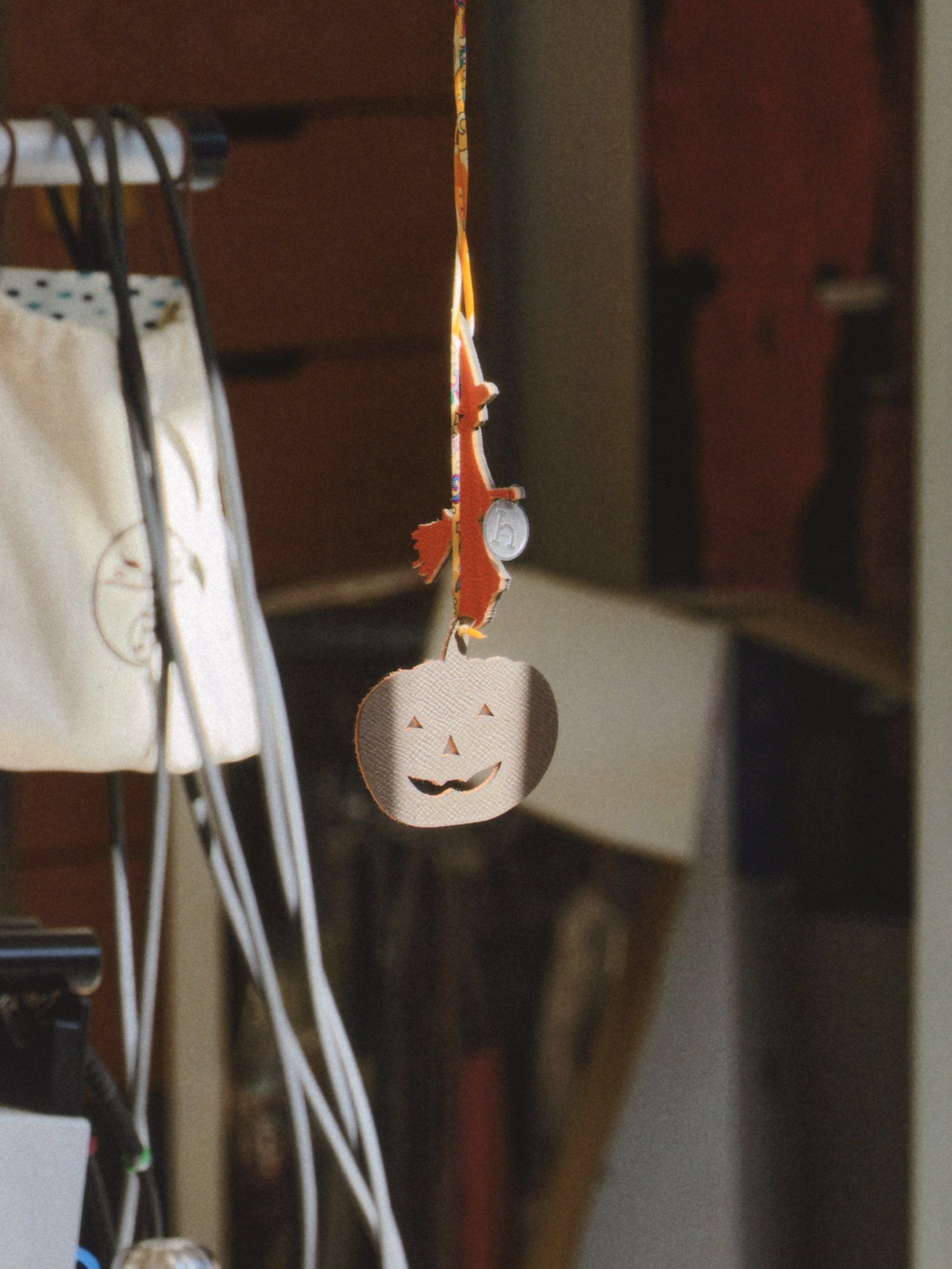

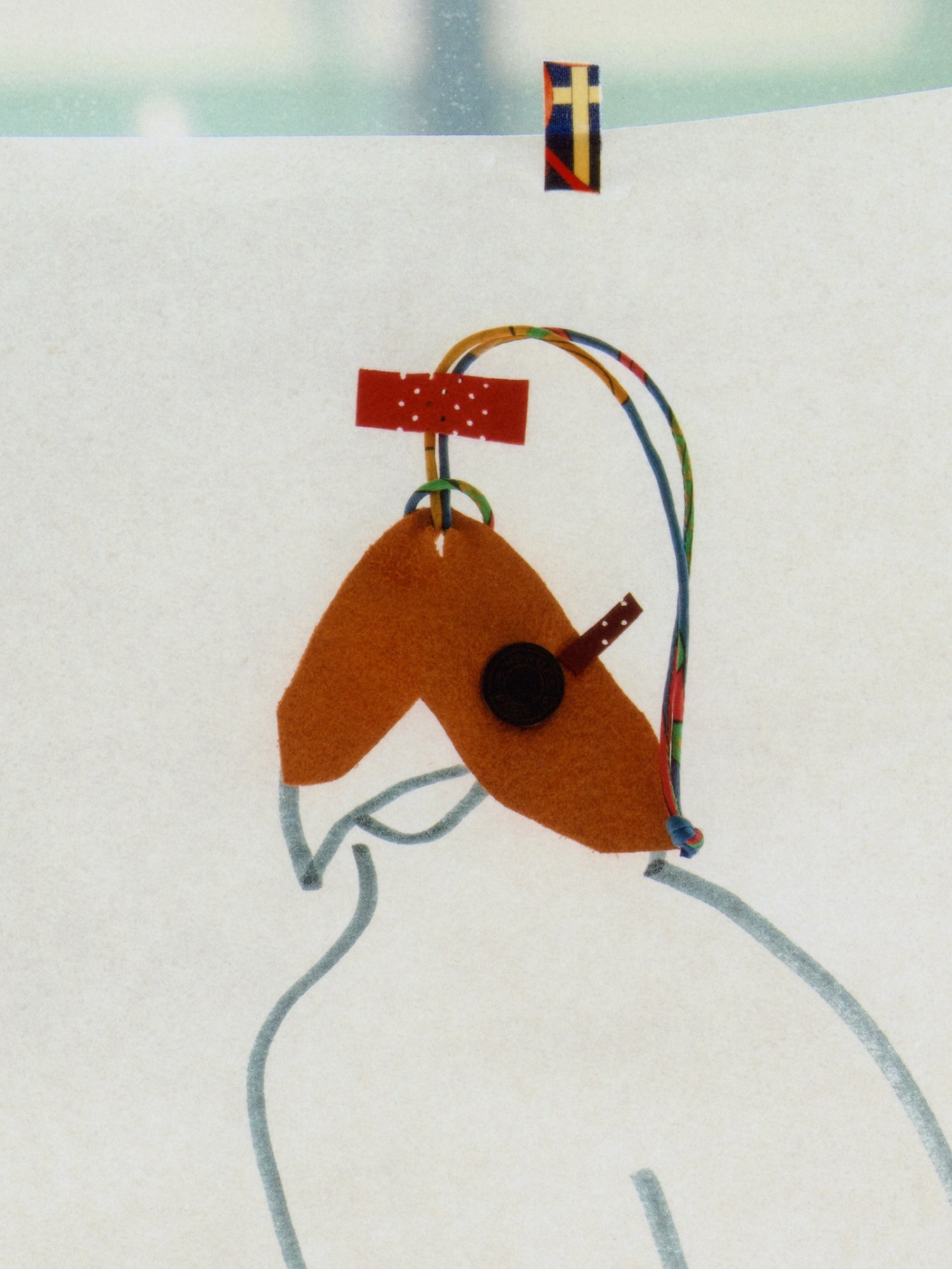

Often, petit h’s products defy the easy categorisation of the brand’s tentpole product categories — clothes, accessories, homeware, furniture, equestrian equipment — instead offering left-field objects that marry irreverence and function. A pair of measuring scales, crafted from leftover leather straps, slight defected porcelain bowls, and recycled paper from packaging. A cabinet of drawers, entirely panelled in leather with handles taken from crocodile handbags. Sticky tape, lined with silks and leathers left over from scarves and bags. It’s like a bric-and-brac marketplace, with the world’s most expensive materials.

It’s here in the atelier – with its polyrhythmic patter of worktools and machinery, and double-height windows through which natural light streams – that petit h’s weird and wonderful objects come to life. Walking around, it feels a bit like Willy Wonka’s chocolate factory. One craftsperson is applying grained leather to a bookshelf that, on second glance, is in the shape of an elephant. Another is applying leather handles — presumably defected or leftover from a Kelly bag — onto porcelain vases, the result resembling earthenware with both walking-to-the-well simplicity and urbane leather straps. On one worktop, a plump garden gnome is given a shearling waistcoat and a beard of fringed slate-coloured grained calfskin. There is no aesthetic throughline, just a joyful sense of humour.

“At petit h, we don’t really draw, the starting point is the fabric,” Godefroy reflects, handling some of his delightfully Frankensteinian designs. While the reversed supply chain offers limitations — everything must be made from discarded materials — he opts to see it through a glass-half-full lens. “It is a strong tree, with all the different métiers, and we have this freedom to go from one to the other, like a bird,” Godefroy reflects. “We take every material to make the nest.” The real challenge, he adds, is figuring out how to combine leather and porcelain to create something from materials that were never meant to go together. Some objects take as many as three to five years to come to life, simply because an idea will not have the materials it requires. “At petit h, we don’t really draw,” Godefroy explains. The starting point is the fabrics, which we combine. It’s a really intuitive process.”

You might think of Hermès’ fashion aesthetic — led by the direction of its menswear designer Véronique Nichanian and womenswear designer Nadège Vanhee-Cybulski — as deliciously neutral BCBG timelessness, sort of like the sartorial equivalent to ASMR. petit h, by contrast, is a jolt of colour, wit and irreverance; it is a counterpoint to the seriousness often assumed of Hermès on account of its high prices and waiting lists. With the materials they are given, they create objects that are far-ranging in their aesthetic, almost Dadaist with their eclecticism. Animals are a recurring theme — because, who doesn’t love animals? — and key to each object is that it serves a function, albeit with a sense of humour. Even teddybears can double up as cushions, Godefroy is quick to point out.

“We actually don’t want, at all, to stylise something‚ to have only a ‘petit h style’ would be the worst thing,” explains Godefroy. “We really want to have this possibility to move with what we receive and with the creativity in our direction. But to me, it’s quite important too, when we do events in Paris or abroad, to try to tell stories to the customer with a special scenography. We have this feeling that gives a direction, otherwise, it’s like a big bazaar. We want diversity with no limits in a frame we impose on ourselves.”

Part of its success, in developing “recipes” for products with its constantly changing menu du jour of materials, is that petit h is one of the only parts of Hermès’ business that invites in collaborators from different fields. “It could be illustrators, artists, designers, anyone who has a sensitivity to the material, and understand the know-how,” Godefroy says. Rather than an isolated design team coming up with ideas that are then executed by the craftspeople, everything works in tandem with each other, befitting of the reversed process. Craftspeople are just as much designers as they are makers, and designers must muscle in on worktops. “Here, that operates everything because we find the innovations downstairs on the tables. There is no engineering part from one side and making part on the other. Everything is linked on the table once the idea arrives.”

The limited production of these objects also make them even rarer than the lusted-after Birkins and Kellys. Though petit h now has a dedicated retail space on Paris’ Left Bank, it is still sold globally through ephemeral pop-ups that travel the house’s global network of stores. “Sometimes we have only two or three pieces, and then when it’s not more, it’s done,” smiles Godefroy, who adds that customers often request certain colours or styles that just aren’t possible to create. Often, those customers follow the travelling exhibitions and retail pop-ups around the world, hopping across continents eager to snap up whatever limited edition objects are available. “You need to follow us all around the world when you go abroad,” Godefroy smiles, perhaps taking pleasure in the fact that petit h isn’t so beholden to custom orders and seasonal collections.

But given that sustainability’s end goal is zero-waste, it presents somewhat of a paradox for petit h. The less offcuts and surplus materials, the less Godefroy and his team have to work with — even if demand for their upcycled objects is growing. “It is a paradox, but the craftspeople are very attentive to the material,” he reflects. “When they cut something they always keep the piece that are not used. The whole workshops have that in mind too: to keep the material, and be very careful with the leather, which is really precious and they don’t throw anything away anymore. They have the same state of mind as petit h, to really keep everything maybe to redo something with that.”

However, given that the house is all about handcraft, there’s always room for human error, luckily for petit h. Besides, judging by the rolls of rainbow-coloured leathers and draws of handles, buckles and defected ceramics in the ateliers, Godefroy and his team have plenty to work with. “The recipe of petit h is material in the middle, creatives and artisans on either side,” he adds. Sustainability has never seemed more delicious.

Credits

Photography Jack Wilson