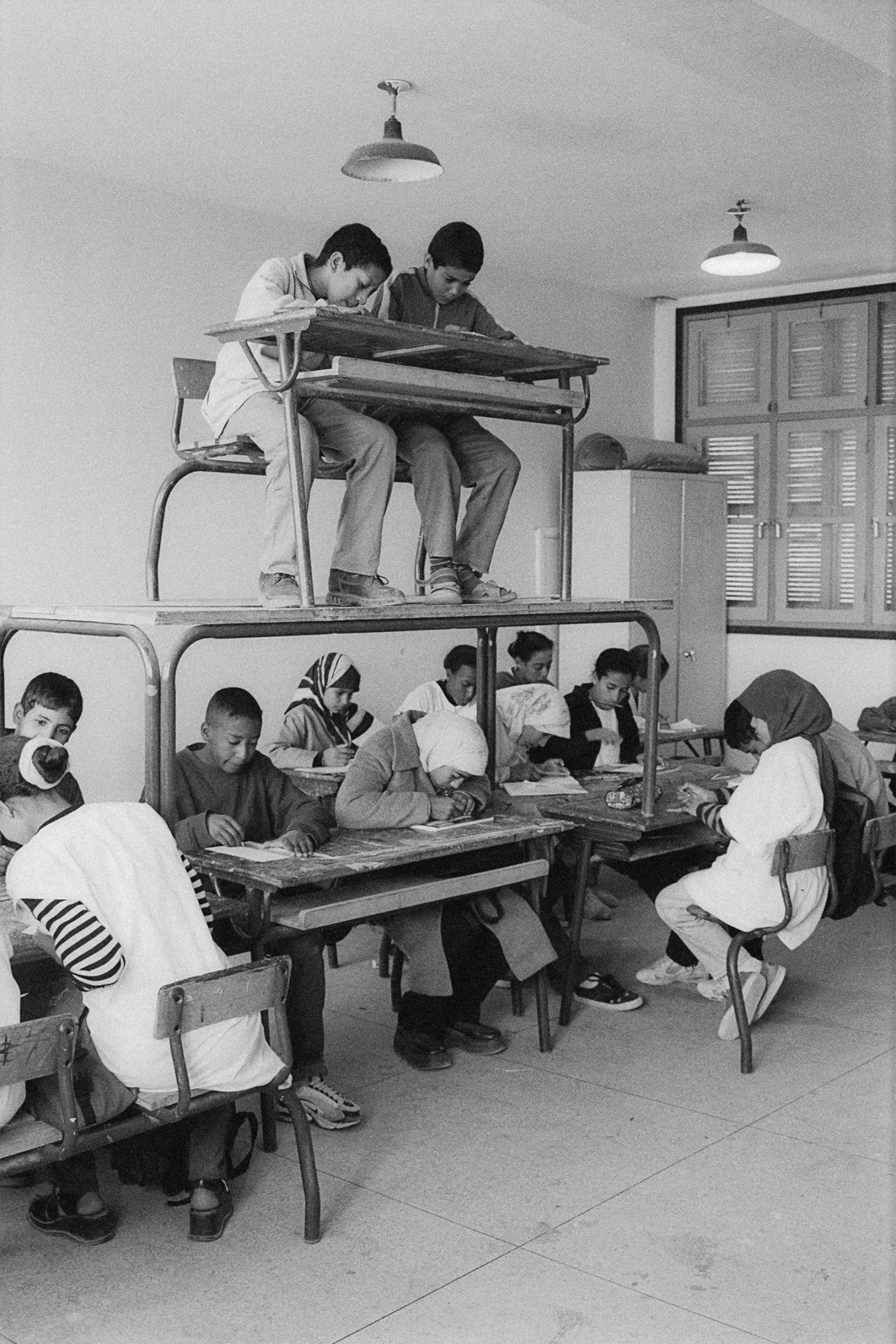

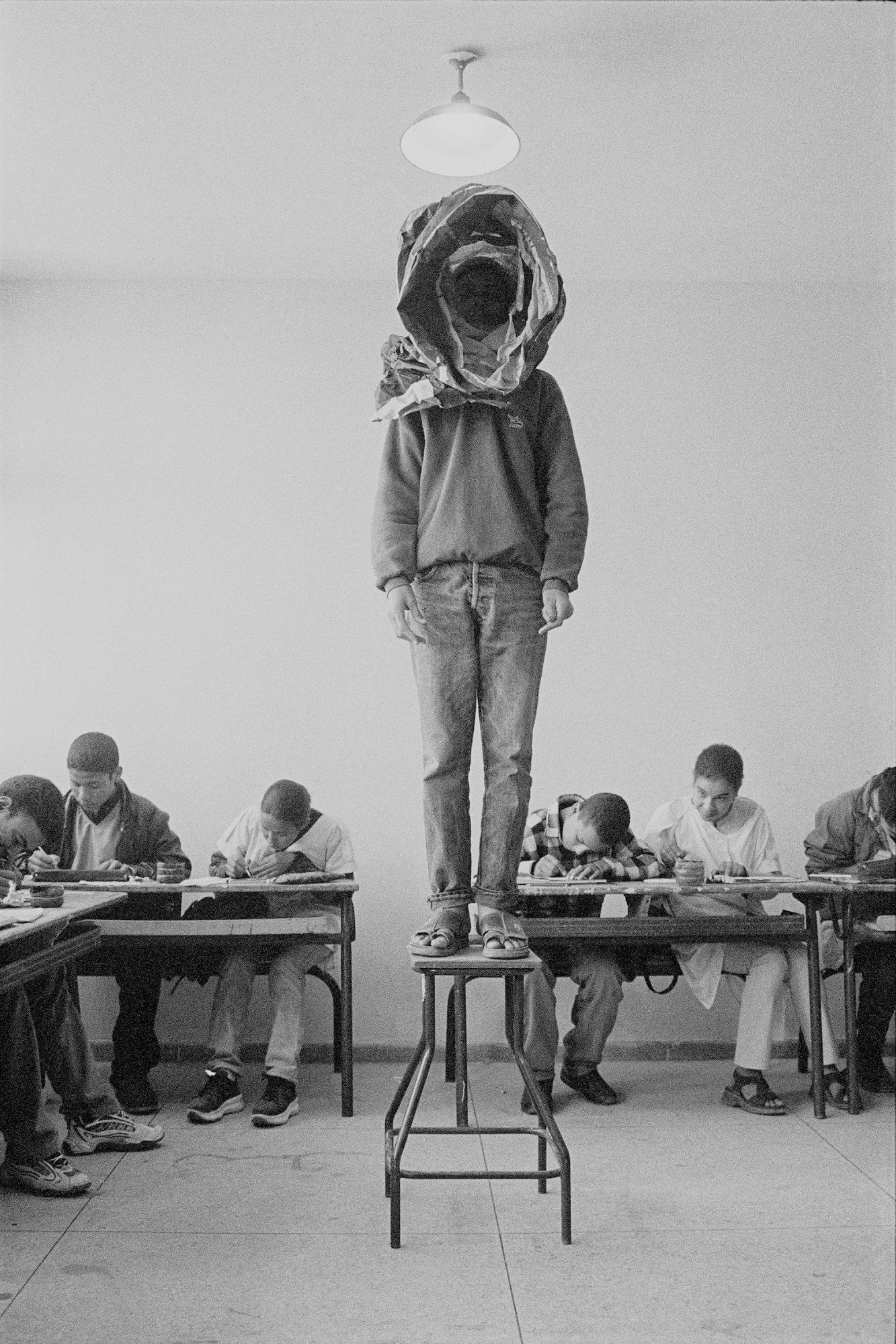

The quietly surreal arrangements of Hicham Benohoud’s La salle de classe (The Classroom) were manufactured by the photographer while working at a school in his native Marrakech between 1994 and 2002. In one scene, a desk is elevated to create a double-decker workstation, two students up top and two below. In another, a teen emerges from a mountain-shaped cloud of white paper, his head practically touching the light fixture above as his peers work undisturbed beneath the mountain’s edge. “They were my actual students,” the photographer clarifies today via a translator, “I was their real teacher.”

Describing the project as a product of chance, Hicham characterises it almost as a balm for a heightened sense of frustration he felt in the profession. “Teaching art was a boring job. I had four classes a day, and for 10 minutes, I would explain the assignment, but for 50, they were drawing or colouring, and I would just drop in,” he says. “I was going round and round like a madman, so to remedy this, I set up a photo studio.” The series, which in full totals more than a hundred black-and-white photographs, has since been exhibited internationally and, in 2001, was released in a monograph by French publisher Éditions de l’Oeil. Currently, it is on display in Bologna as part of Foto/Industria (through 26 November).

One of a dozen exhibitions on show at the Italian biennial this year – focused on the intersection of industrial and work photography, its sixth edition recently opened under the umbrella theme of “Game” – Hicham’s work occupies San Giorgio in Poggiale, a former Roman Catholic church, restored and reopened as the Biblioteca d’arte e di storia in 2009. Presented here in a library context, the images are stationed above tools for learning and positioned in a loop that swirls around the building’s main floor; as the space’s centrepiece, its staging appears consistent with the conditions of the work, the additional reading spaces stand-ins for the pictures background players.

First working with a camera in 1989, just as his secondary school art teacher career began, Hicham recalls that his wider creative practice was the principal trigger for engaging with the medium. “I had a few shortcomings in drawing and painting techniques, so I needed documents that would enable me to reproduce them faithfully. In Morocco, we don’t have museums where you can go and copy the Great Masters, so I had the idea of taking photos of my students,” he shares. “The project wasn’t clear-cut or well-defined, but it enabled me to refine my artistic approach, have fun and keep busy.”

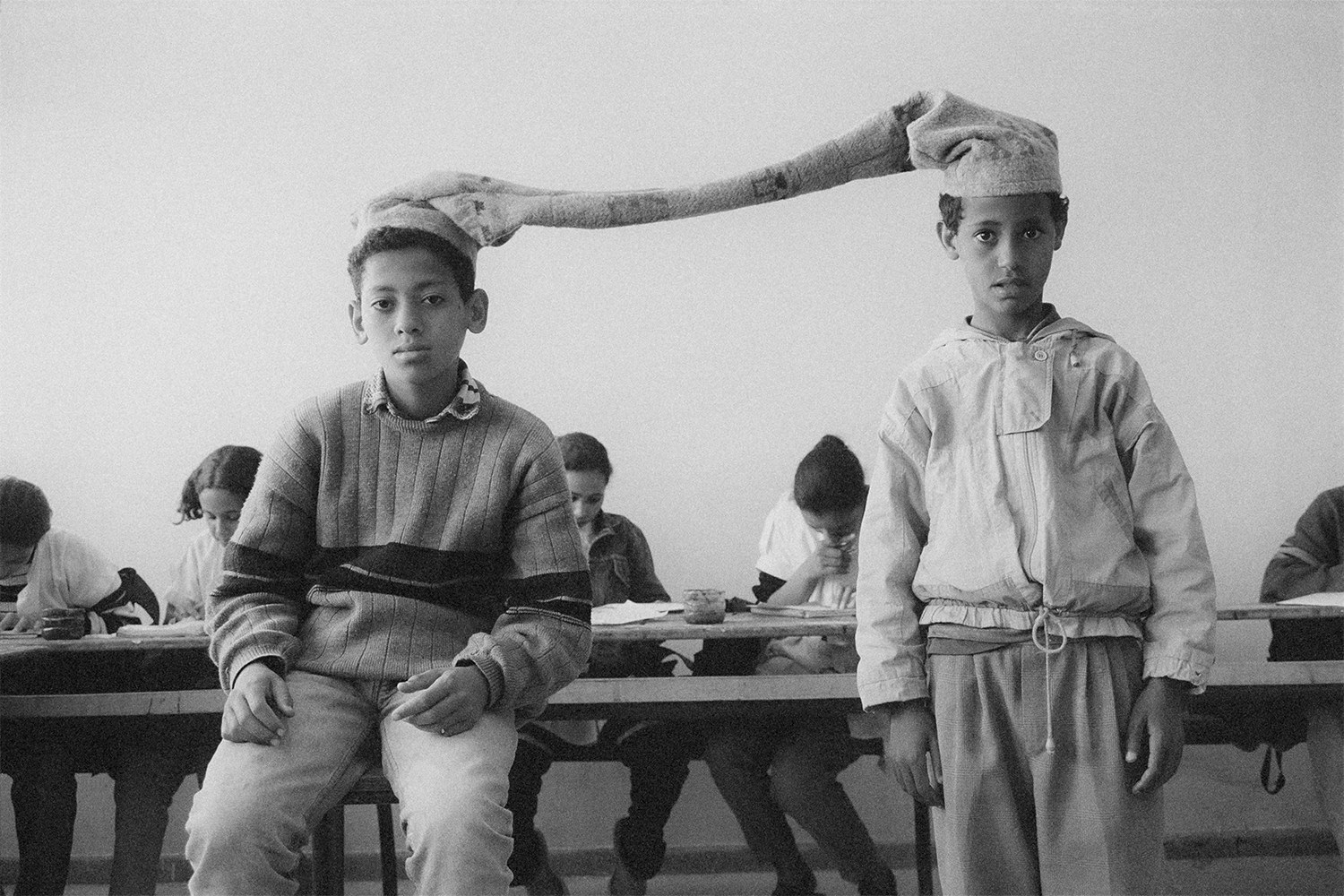

These early portrait sessions soon evolved into the more elaborate configurations that feature in La salle de classe, for which Hicham would construct storyboards with directions for his subjects. “When we first started, they were a bit tense. They’d have trouble ‘playing the part’,” he tells me. “I gave them general instructions, such as standing on one leg and holding an object with one hand, but I didn’t specify whether it was the right or left hand, for example. They would often find my suggestions surprising, even crazy – they’re used to family photos at religious celebrations or wedding parties.”

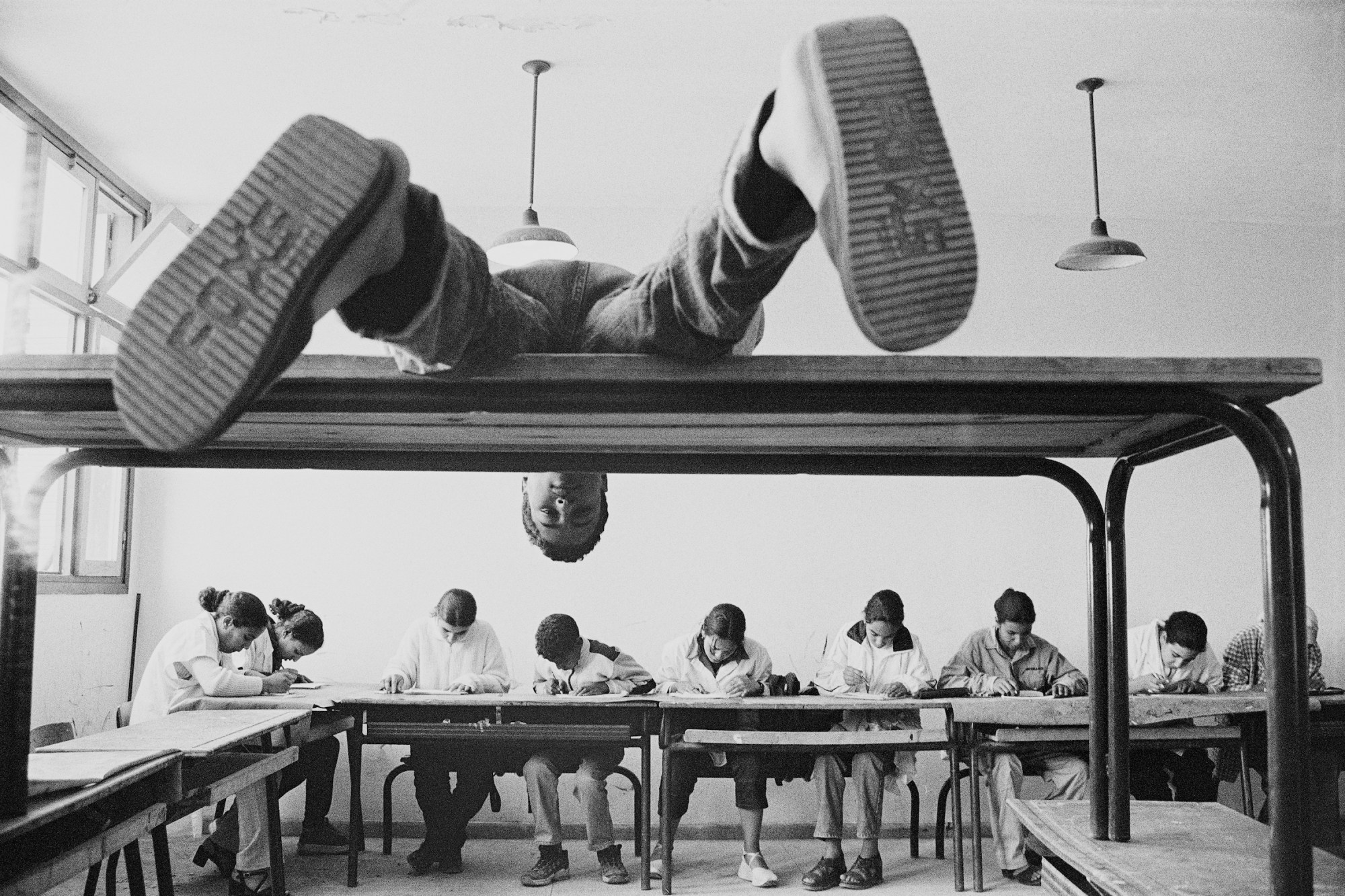

The role of a photograph for many of Hicham’s students at the time was largely more formal, saved for a big social event or a school photo, wherein a Polaroid was usually employed. In this context, many regarded the camera as akin to a UFO, he says, adding: “I’m almost allowing them to get into mischief in the classroom.” Responding to the work in 2001, director of Agence VU and Galerie VU Christian Caujolle observed, “They all like to pose because they respect their teacher, because they never, outside of photo sessions, have the opportunity to indulge in such strange behaviour in class as lie on the ground or get on a table.”

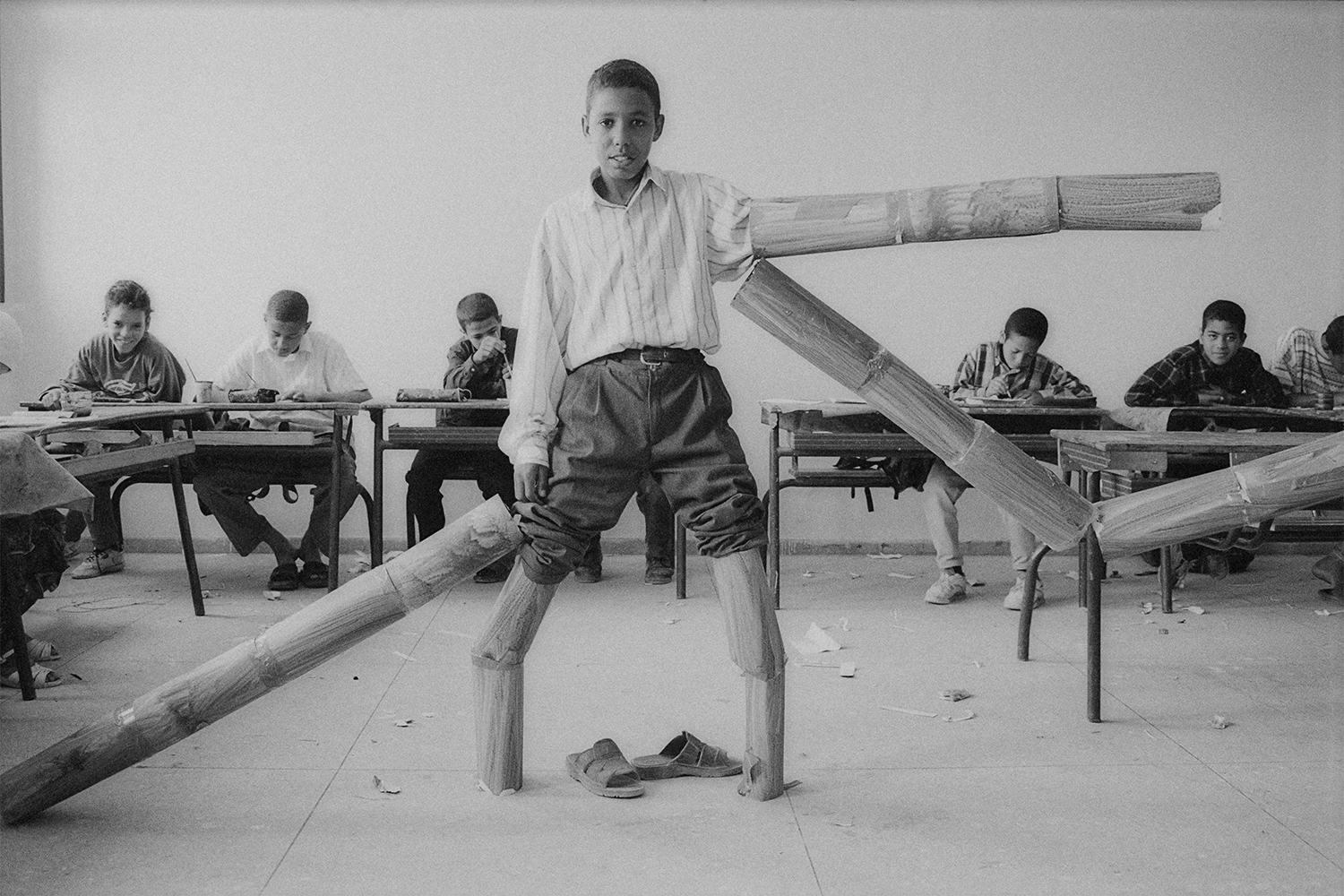

Posing his models in these curious scenarios, sometimes with another student holding up a piece of cloth behind them (Hicham began incorporating the full scene of the classroom into the pictures after noticing that their fingers often made it into the frame), the photographer was able to play with props and explore otherwise improbable situations with his students, as in the image of a boy whose limbs are extended with cardboard tubes, evoking some of the angular physicality synonymous with scarecrows. “Shooting was like watching a play in which they were invited to take part,” he says. “In general, they found the shots very funny because they’re unexpected, and it kept them occupied. For a few seconds, it allowed them to step outside the strict confines of the classroom and experience a dreamlike moment.”

Visually striking, with a kind of softness that stems from the vague haze of the monochrome palette, there is a heavier significance at play, here explains Hicham. He applied his dissatisfaction with a society he felt was in limbo and an overwhelming sense of repression – a consequence of strict cultural and religious taboos – to the work. “I wanted to talk about confinement. At the time, as a Moroccan citizen, I felt locked up in my own country. I couldn’t travel abroad because it was hard to get a visa for Europe, and I was also locked in professionally, condemned to a job with no prospects,” he says. “I longed for freedom and dreamed of being an artist. Socially, I felt trapped because of heavy traditions that hadn’t changed in several centuries.”

Now mainly based in Paris, the photographer’s work continues to foreground the social conservatism upheld in Moroccan society, moulding his discontent with uniformity into the similar surrealist aesthetics of his earlier practice. In Acrobatie (2017), he photographed acrobats performing in their own homes, casting their families as bystanders; in 2015’s The hole, he dug cavities into floors, ceilings and partitions of the home, photographing limbs dangling from walls. “The common thread between this series [La salle de classe] and the later ones is the setting,” Hicham says, alluding to the physically tight expanse of the classroom and these domestic spaces, a reference to the perceived restraint of his subjects’ wider environment. “It’s just the context that changes.”

While collaborative in its execution, La salle de classe was always a singular endeavour, though he extended certain decisions to the students that no doubt shaped the tone of the pictures. “I never asked for a particular expression; everyone does what they feel. To my surprise, I noticed that they rarely smile, I think because they saw that I was very involved in this project and remained deeply serious,” he says. Nearly 30 years since he first undertook the series, Hicham retains a special attachment to the work. “I’ve exhibited these photos in different countries since 2002, so I have the impression that they’ve been taken the day before,” he finishes. “Sometimes, just as I’m about to jot down a new idea for the series, I realise that the project has been finished for over 20 years. My perception hasn’t changed; I still look at them with the same interest and curiosity. They always surprise me.”

‘La salle de classe’ is on view now as part of Foto/Industria until 26th November 2023

Credits

All images courtesy Hicham Benohoud and Foto/Industria