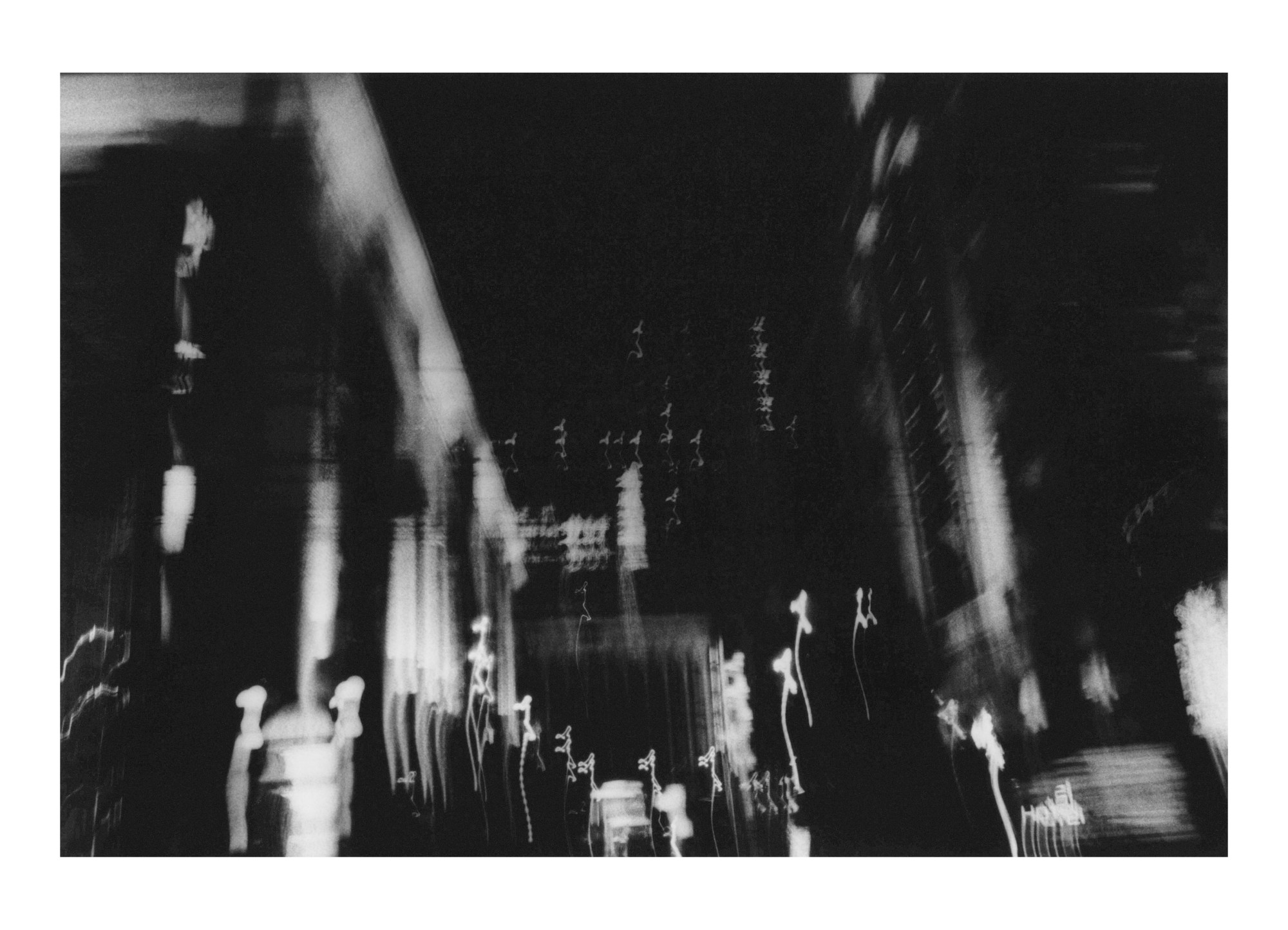

Kabukichō is Tokyo’s biggest and most notorious red-light district. Almost every night of the week, its wide streets are packed with revellers and lit up by noisy advertisements for love hotels, cabaret bars and, most famously, hostess clubs. These are establishments where women are paid to engage in flirtatious conversations with men, pouring drinks, lighting cigarettes and singing karaoke into the early hours.

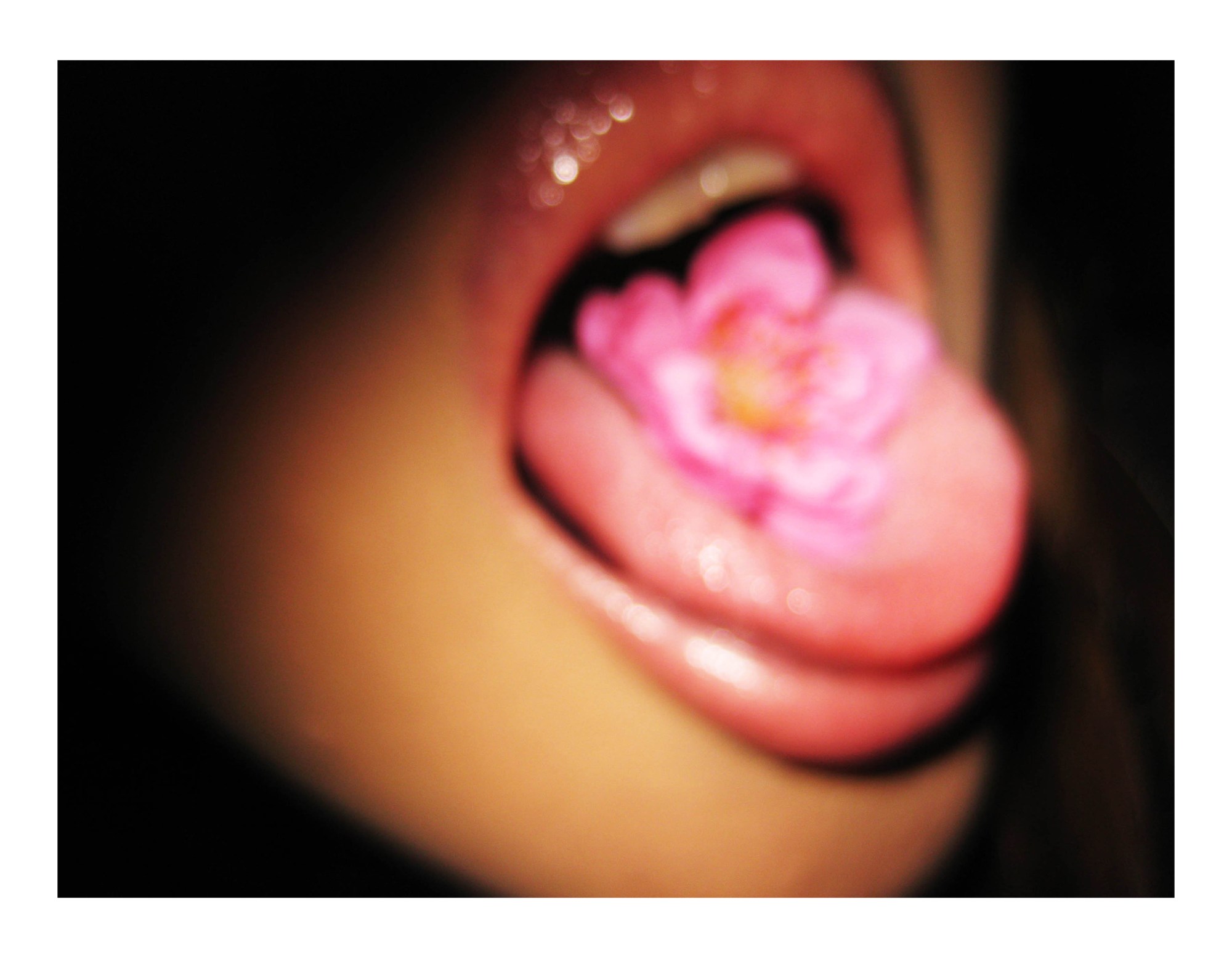

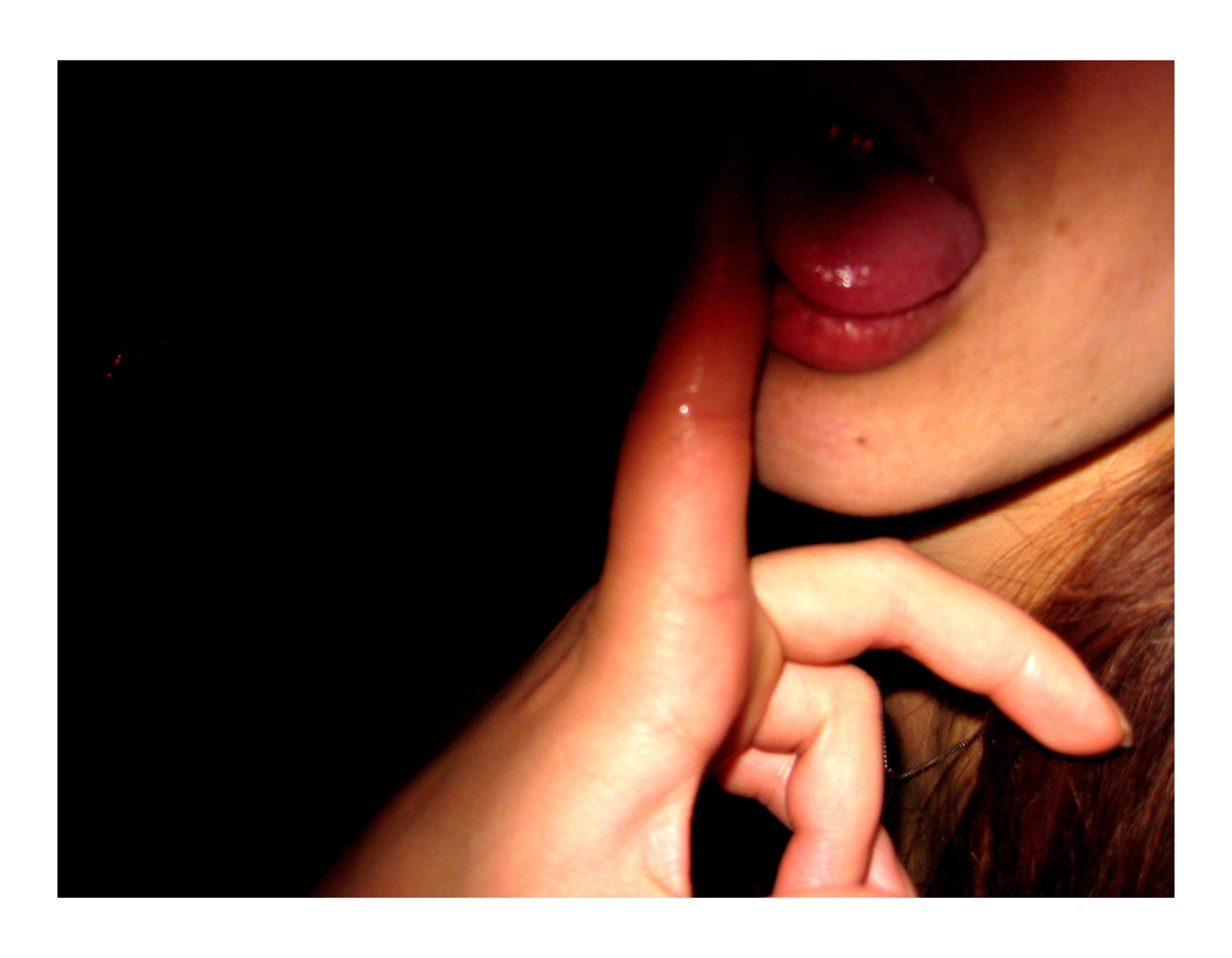

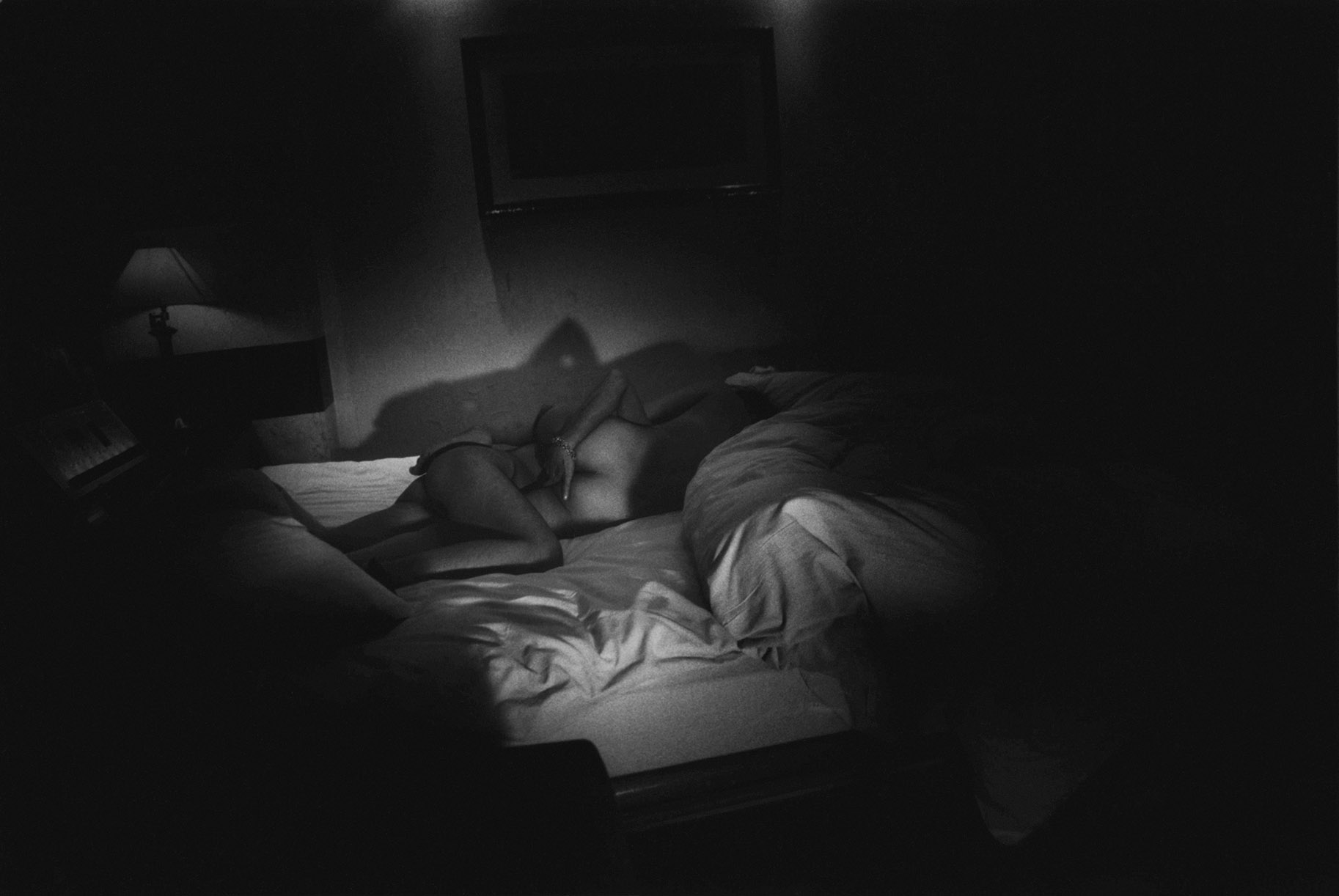

Hideka Tonomura was a hostess for over 20 years. She worked in red-light districts all over Tokyo, in Roppongi, Ginza and Akasaka, and adopted different names for each. In Kabukichō, they called her Yukari. While working as a hostess, she regularly contributed to erotic magazines, known in Japan as “erohon“. “I was making secret photos in the club and submitting a diary of daily erotic images. It was just for fun,” she says. In the early days, she’d turn up on shift with a tiny camera disguised as a clutch bag. Eventually, with the permission of the other hostesses, she started shooting with full-blown flash, capturing the cycle of debauchery that charged through each and every night.

Kabukichō was the place Hideka took the most photos, but it was also the place she loathed most. “It was like a human dumpster for lust, greed and desire — a place that swallowed up and spat out the worst of humanity,” she says. “It wasn’t just a place to satisfy sexual desires; it was a place for people to forget who they were… Customers would come to drink for one night, but us women were there every single day. Our job was to create a dream — one crazy party. When that becomes your reality, you become numb.”

Hideka learned her craft at Osaka Visual Arts School and gained a cult following in 2008 after the publication of her first book, Mama Love, a shocking project that documented her mother’s affair (that ran on i-D last year). Five years later, she followed it up with her photos from Kabukichō in a book titled They Called Me Yukari. Now, a decade on, she is launching a second edition of the publication alongside an exhibition currently on display at Zen Foto Gallery in Tokyo.

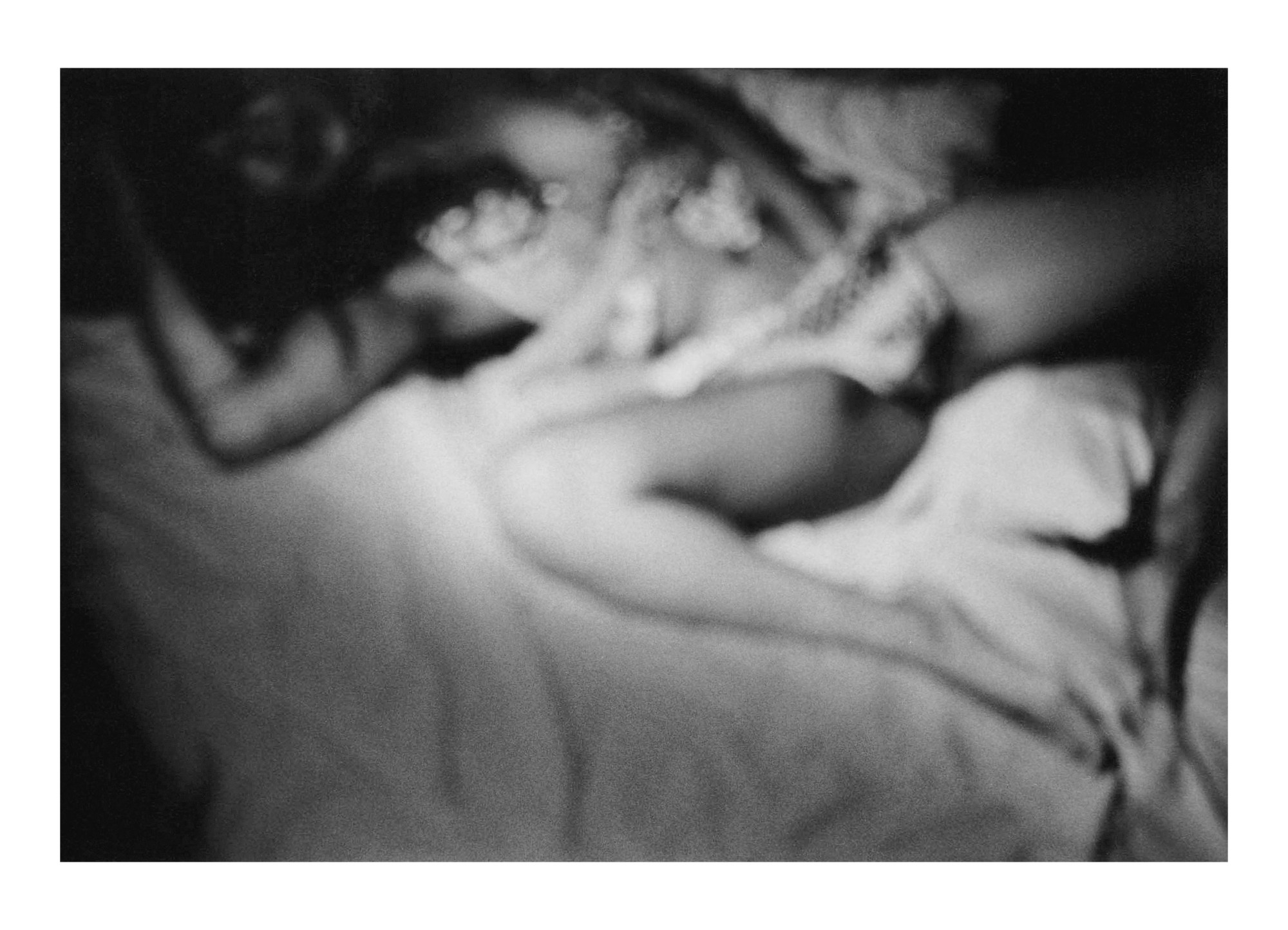

The sequence is like a fever dream — a breathless rush through the complex dynamics of sex, death, desire and power. Kabukichō has been documented by countless photographers, writers and filmmakers, but they are almost exclusively men — usually customers, and sometimes foreigners. Hideka’s images come from within the clubs and within her own psychological landscape. “It was a dark time in my life,” she says. “When you spend that much time in a place like Kabukichō, which is charged with so many conflicting energies, your soul begins to wander away from you.”

Despite all the mental and physical struggle, Hideka didn’t always hate the job. Hostessing is a lucrative industry, and that can be liberating, especially in a patriarchal society like Japan where the gender pay gap averages 22 per cent. “At the club, women are in control,” Hideka says. Even so, can women ever be considered equal in a system that allows their bodies and their attention to be sold as commodities? “It’s convoluted… Because the culture of hostessing in Japan exists because of gender inequality,” she says. It’s not just about money or power either. It is about sex and death, two themes that are deeply intertwined in Hideka’s work. “In Kabukichō, girls disappear every day. They’re dying of suicide, from illness. I imagine that people who work in hospitals become desensitised to the presence of death in their workplace. It’s the same in a hostess bar, unless you become used to death, unless you numb your emotions, you cannot work there.”

These contradictions can be felt in Hideka’s images. They are murky and, at times, alarming, but they are also deeply alluring. How does she reflect on Kabukichō as a place, and this body of work, a decade since she first shared it with the world? “I could never go back to Kabukichō now. It’s like there’s an invisible fence around it, as though if I stepped a foot inside, I would be electrocuted,” she says. These images were born out of dysphoria, but on reflection, Hideka realises they saved her.

“The boundary between desire and hope is paper thin. When I took these photos, I realised that within desire, there can be hope, which is the will to stay alive — even in the ugliest times. I learned that in Kabukichō, and that saved me in my darkest hour.”

‘They Called Me Yukari (New Edition)’ is available to purchase here

Credits

All images © Hideka Tonomura, They Called Me Yukari, courtesy of Zen Foto Gallery.