There are few creative mediums quite as able to disturb the neat, linear passage of time as photography. While an image is the product of a given moment, sometimes, what it captures can resonate so faithfully with the context in which it’s viewed that past and present seem to coalesce. It’s a feeling you’ll often experience on viewing Hot Moment, the newly-opened show at East London artist-run gallery Auto Italia.

Curated by Radclyffe Hall, a “concomitant group of artists and writers dedicated to exploring culture, aesthetics and learning through the lens of contemporary feminism”, Hot Moment exhibits the works of Tessa Boffin, Ingrid Pollard and Jill Posener, “three photographers for whom lesbian identity was never a coherent category to be straightforwardly translated to image by the camera.” But perhaps more crucially, the show constitutes a densely layered snapshot of an era in which the marginality of queer identity and experience encouraged the development of radical forms of expression, both away from and within full sight of the mainstream. Hot Moment, as Radclyffe continues, is “an exhibition of dyke photography made on the threshold of intimacy and public life during the 1980s and 90s in London.”

Those with keen eyes for British socio-political history will clock that the dates given above neatly overlap with some of the most right-leaning years in the country’s post-war history, bringing decades of institutional prejudice with them. “Hot Moment engages with many of the key political struggles in late 20th-century Britain: feminist battles over reproductive rights, the onset of HIV/AIDS in the UK, the legislation and consequences of Section 28,” explains the curatorial body.

Though these conditions may have been specific to the UK’s Thatcher-era, the use of photography as a means of rallying against systemic oppression still resonates across the world today. “The political discord of the 80s and 90s was never fully resolved, and today we are seeing the legacy of these struggles surface again in the form of transphobia, racial profiling, the erosion of immigrant rights, religious discrimination, and a swing to the right,” Radclyffe continues. “The exhibition also shows how photography could serve as an arena in which to retreat from these conflicts and form creative communities in spite of mainstream politics.”

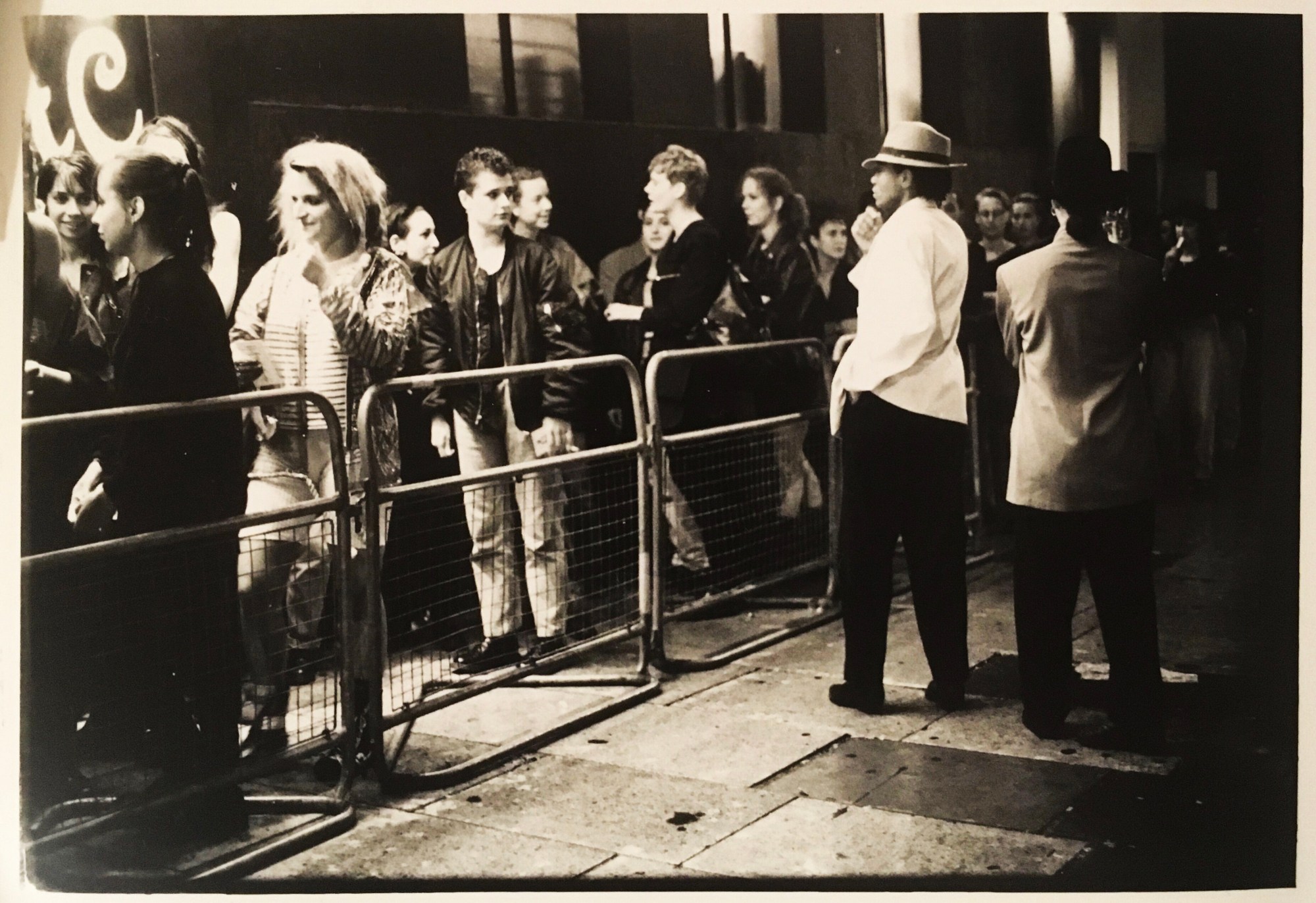

Terms like ‘arena’, ‘retreat’ and ‘community’ feel particularly salient when looking at the work of Ingrid Pollard, whose mixed media contribution to Hot Matter comprises artefacts of “collective activism from the 1980s and 1990s by black women,” including “documentation of Club Sauda, street performance, and interviews with writer Audre Lorde.” It’s in the first of these that we most clearly see the means by which bodies that exist at harsh intersections of mainstream oppression embraced their marginal status to create spaces of active self-reclamation, celebration and support.

“Club Sauda was a monthly club night run by and for black women. We did it all: the publicity, all the background stuff like the lighting and sound etc for events, which usually took place at the A Women’s Place near Holborn,” says Ingrid. “The first part of the evening was a series of performances. Over the years this included singing, dance, poetry, comedy, mime and more. The rest of the evening was DJs and dancing. Some women came just for the performances and some stayed for the whole evening.”

Across joyful black-and-white portraits of singers caught mid-performance and a video installation, viewers are offered a dynamic insight into the facilitating energy of the space. While joy and lightheartedness are certainly to be read in the work, Ingrid is quick to underscore the political gravity of the Club Sauda project. “Most Club Sauda evenings would start with some wise words, highlighting a particular topic or idea,” she explains, “it set the tone for the evening and in a way reminded us that we have come together for ‘smiles, laughter, love, dance, theatre and music’; activities like these are political.”

Club Sauda, effectively, represented an oasis in a nightlife landscape otherwise unwelcoming to black queer women. “We could never find anywhere that felt truly comfortable for us queer women of colour to rave and celebrate ourselves,” writes Skin, lead vocalist and guitarist of Skunk Anansie on Instagram. “In those days being queer and black came with a shitload of hostility even from our own community; [that’s not to say that] some gay clubs were white only, but you knew it when they didn’t want you in there! So we decided to do it ourselves, luckily Ingrid always had her camera on her.”

Jill Posener’s work more evidently treats the interaction of queer identity and public space, particularly the infamously queer-hostile media environment of the time. A jobbing photojournalist herself, she regularly contributed work to mainstream press outlets, outlets which routinely peddled racist, sexist and homophobic agendas. This uncomfortable bind spurred a practice that cleverly exposed the emptiness of the performances that prop up supposedly infallible pillars of power.

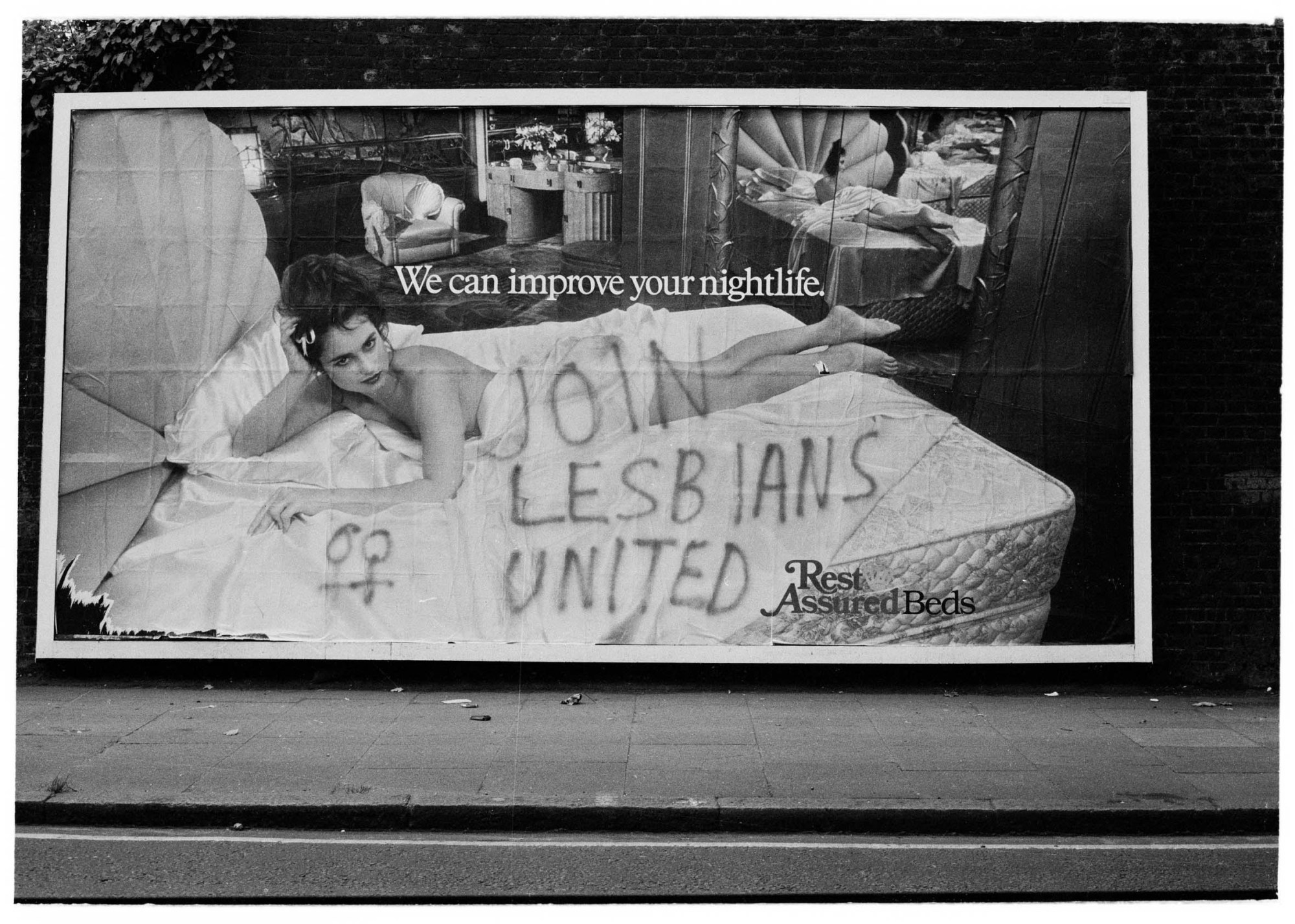

Images of a robotically grinning Margaret Thatcher holding terrified children are set against pictures showing members of experimental theatre company Blood Group holding brashly titled editions of the Sun. And in the exhibition’s most immediately eye-catching work, mounted on the gallery’s front facade, a surly bed company advertisement reads ‘We can improve your nightlife”, with “JOIN LESBIANS UNITED” sprayed just below. With just a spray paint can and the flick of a wrist, the heterosexism of commercial advertising is wittily undermined, along with the tired, paranoid propaganda that queers are agents on some sort of insatiable recruitment drive.

A similar undercutting wit colours the late Tessa Boffin’s photos, whose staged narratives ridicule the common grounds for the oppression of genderqueer bodies, while also proposing the actualisation of queer identity as an act of resistance and liberation. The King’s Trial, 1993, highlights the role of the tabloid press in the public crusade against expressions of FTM crossdressing and transmasculinity, reacting to a series of media-abetted trials in which numerous victims were charged with posing as men to seduce ‘innocent’ straight women. In a deliciously cynical lampooning of media autocracy, male-passing figures pose smugly on posters that read : “THIS IS A WOMAN. SHE IS DRESSED AS A MAN BECAUSE:” followed by four tick-box “reasons why”.

Though the photographic practices of the three artists differ — at times markedly — they are bound by a mutual dealing with themes of fantasy or escape, creating and documenting spaces in which the actualisation of identity becomes an act of political revolt. It’s what makes the works on show so pertinent today — not only do they remind us of precedents set for us in times that felt as bleak as they do now, but they also offer an insight into what can be done. “Boffin, Pollard and Posener’s images are pro-sex, pro-queer, and with an inclusive approach to feminism, and so they speak back to us in new and vital ways that are no less relevant than at the time they were taken,” Radclyffe concludes. “When we were putting up Hot Moment, Ingrid even mentioned that none of the photographs seemed old or distant. In a new and uncertain decade for lesbian and queer public life in the UK, maybe this exhibition is both a reminder about where we come from, as well as a call to action.”