Kazim Rashid is a London based creative director and artist. For the last 10 years he’s worked with brands and artists, designing their creative strategies and concepts. Now the 30-year-old has just finished his debut solo artwork, a tri-narrative video titled 2001: Pressure Makes Diamonds. “It’s quite autobiographical” he says. “The story of a boy, in a very particular time, in a very particular place, which just so happened to have this relationship to a global narrative.”

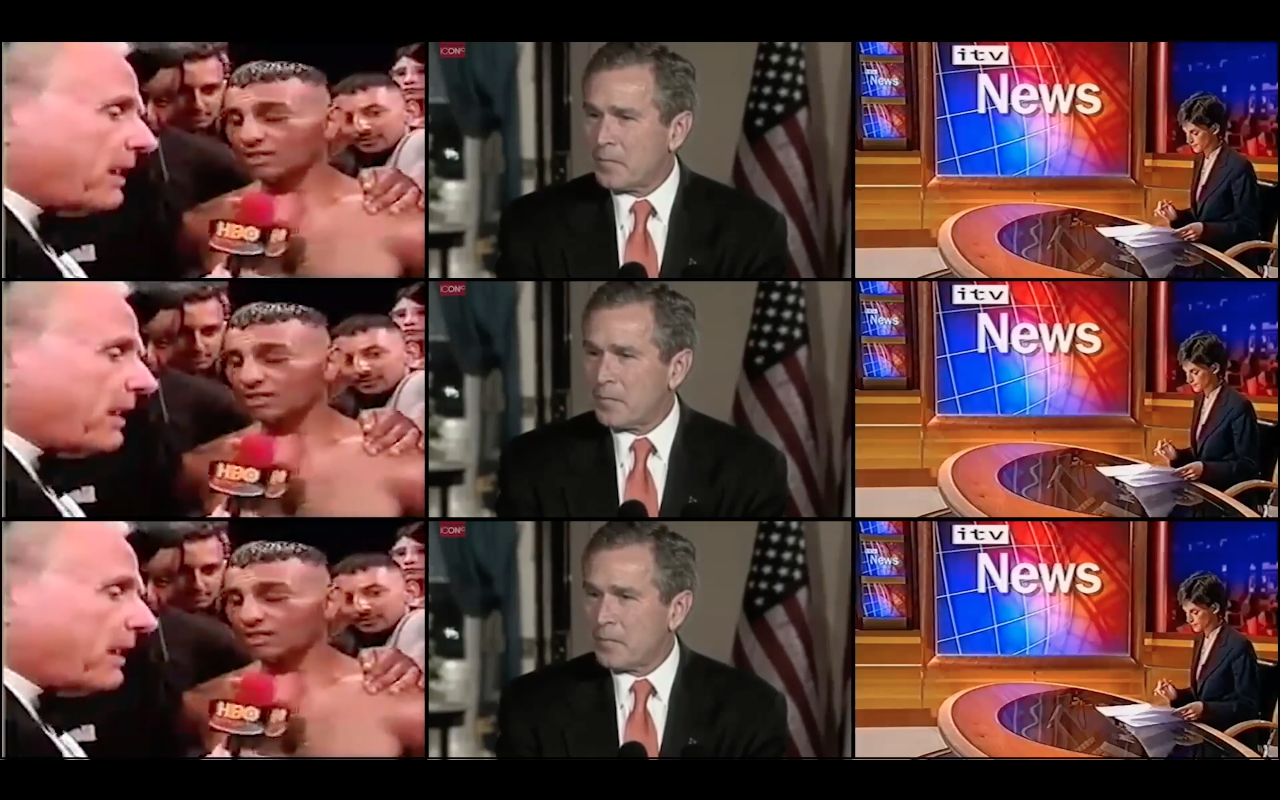

The video focuses on the year 2001 and the impact it had on brown visibility, told through the lens of iconic boxer Prince Naseem Hamed. “2001 is a specific reference because before and after 2001 are two very distinct parts of the story I wanted to tell,” he explains.

2001 was, of course, the year of 9/11, probably the most defining sociopolitical moment of our lives and the start of the US-led War on Terror. For brown people, especially those living in the west, it was also the year that introduced a new experience, a particular breed of racism and discrimination called Islamophobia.

The video depicts British boxer Prince Naseem Hamed as he fights his penultimate fight in April of that year, the first and only he ever lost. Naseem is adopted as a figurative metaphor in the video for the decline and disappearance of brownness in the west. “It was the only fight he ever lost and it happened at the same time as a generation, as well as an entire race of people, were about to lose.”

Born in Manchester, not a million miles from where the Sheffield born boxer grew up, Kazim felt in awe of Naseem and his eccentric persona. Known for his extravagant and controversial ring entrances — which featured music, dancing and costumes — Naseem was an icon and inspiration for Kazim and the kids he grew up with. Even now, Kazim’s voice changes as he discusses the boxer. “I was 12 or 13 when he was at his peak,” he says. “He was so mysterious. This sort of feline figure who looked very masculine but very feminine at the same time. He was skinny, flamboyant and was always moving. As a young teenage boy who is just getting into puberty, Naseem created a wonderful feeling — like you could be anything and still be cool.”

Kazim recalls being a young boy in the UK in the 1990s, a period he describes as being inundated by positive brown representation. “There was Sanjay and Gita on Eastenders, East is East, Goodness Gracious Me,” he says. “There was so much brilliant music. Talvin Singh, Punjabi MC, Apache Indian. And it wasn’t an underground thing — they were charting, you know?” Around the same time there was an explosion in the popularity of Indian and Pakistani food, with the UK’s Foreign Secretary even declaring chicken tikka masala as a UK national dish. Kazim vividly recalls thinking, “Yeah, it’s cool to be brown.’ However, the feeling didn’t last. “Part of the research for the video was just trying to work out what actually happened and where did all the brown people go?”

“I went and sat down and I had a bag with me, and the lady that was sitting next to me just got up and left. And I remember thinking ‘I’m scared too, you know?’ I was just a kid.”

Growing up in Oldham, the town where the north of England’s 2001 race riots started [the worst ethnically-motivated riots in the UK since 1985], undeniably impacted on Kazim’s adolescence, identity and sense of belonging. It suddenly became dangerous to be brown, basically overnight. “The summer of that year, and this was actually before 9/11, my dad was attacked outside our house. I remember thinking, god, it’s so unsafe,” he says. “We aren’t safe at school, we aren’t safe at home, we aren’t safe on TV. Everything is fucked”.

The Oldham riots were reported to be as a result of tension between South Asian and white communities in Oldham. Over the course of three months, tensions broke out in Oldham, Bradford and Burnley and Kazim’s work includes confronting visuals from each. “After 9/11 it was even more severe because everyone was scared,” he says. “Everyone was scared of terror, but if you were brown it’s like you didn’t have the right to be scared.” He recalls visiting London as a young teenager. “I went and sat down and I had a bag with me, and the lady that was sitting next to me just got up and left. And I remember thinking ‘I’m scared too, you know?’ I was just a kid.” Even two decades later, these kinds of things have become increasingly normalised, as Kazim reflects on daily micro-aggressions that can come in the form of “going through airports, being searched all the time, sitting down and knowing that the person next to you doesn’t feel comfortable”.

With 2001: Pressure Makes Diamonds set to be exhibited for the first time, it makes for an interesting time to consider brown representations and their potential for a comeback. “There is definitely a movement starting to happen,” Kazim says. “It’s like there’s a generation of young people who feel ready to address what happened. Maybe the trauma wasn’t so heavy for them because they were too young and so there’s an audacity to what they bring to the conversation.”

Kazim believes social media has played a key part, opening accessibility and allowing individuals to visually present themselves, their views and their identity. “What I find really powerful is people like [British Asian journalist] Simran Randhawa, who have huge amounts of followers and consistently embrace their culture and roots. She’s having a laugh and, to me, that’s radical and really inspiring. That’s where the real change will come from.”

2001: Pressure Makes Diamonds will be exhibited as part of a group exhibition, curated by Loren Elhili, at London’s Rich Mix from 11 to 30 September. Find out more here and follow Kazim on Instagram here.