It’s no surprise that female sexuality is one of the oldest fascinations in art. The ancient Greeks carved soft-skinned, slender nudes into marble — an idealised woman that has become the archetype for Western beauty. Raphael and Titian perfected the passive woman lounging seductively naked for the male gaze during the Renaissance. Japanese painting masters made shunga under pseudonyms and Picasso constructed lustful distortions of the muses he exploited. Painted, sculpted, and sketched by men for men — the art world told women that they have no place in history other than as objects. “Women didn’t have time to think thoughts, they were too busy taking naps naked in the forest,” jokes Hannah Gadsby in her hilarious stand-up comedy show Nanette.

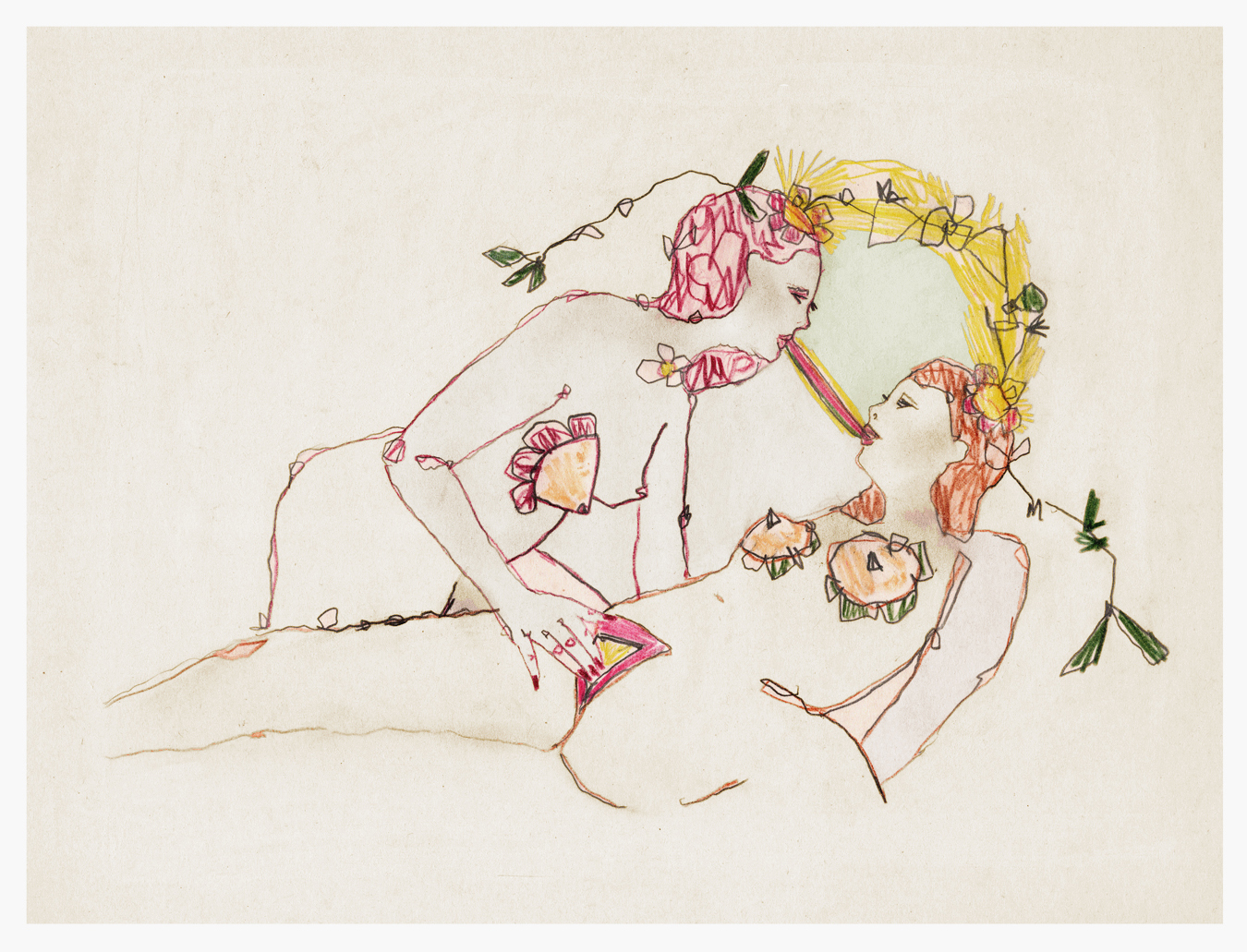

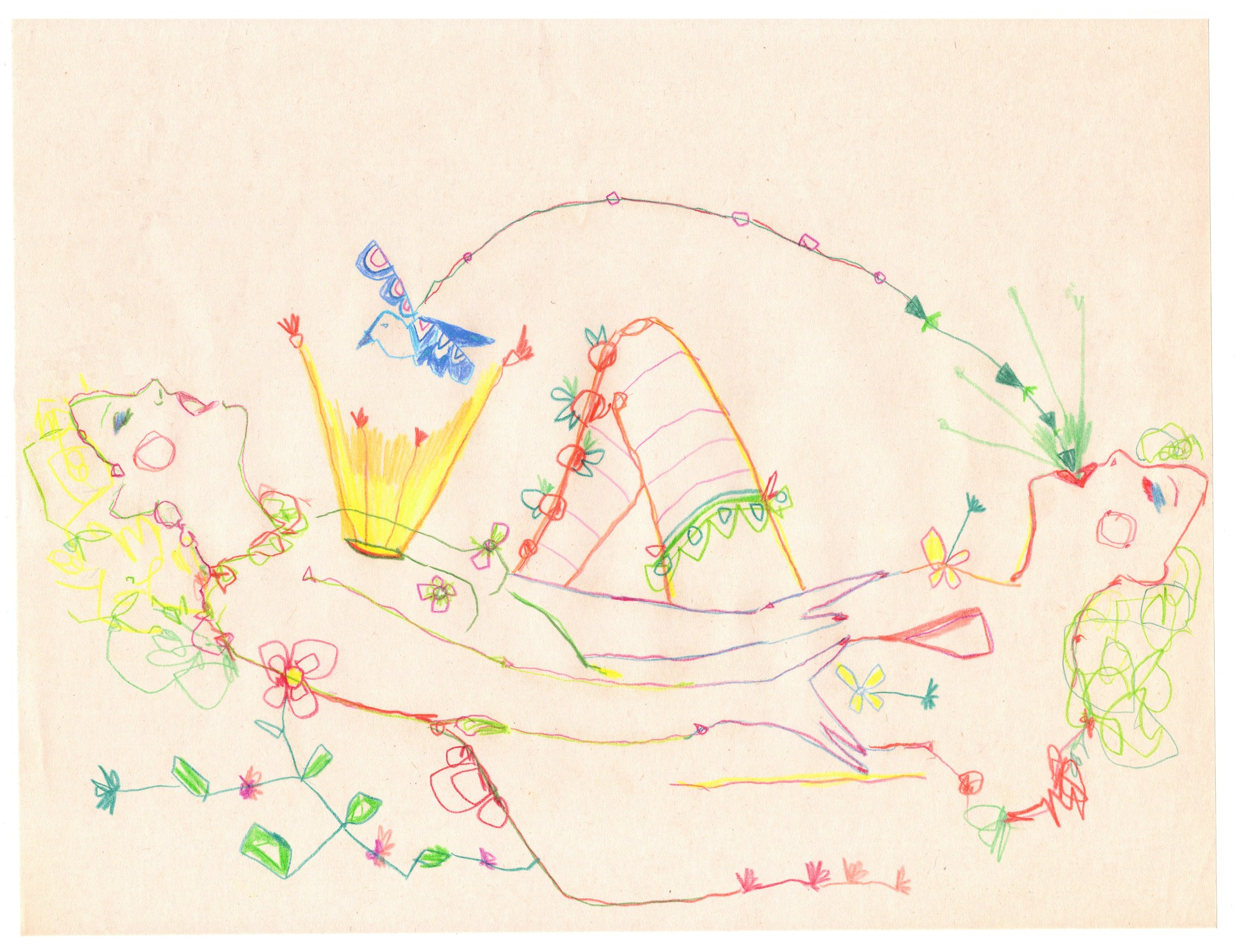

But platforms like Instagram are giving a new generation of women, a space to explore their sexuality on their own terms. Even before the #MeToo movement sparked long overdue discussions about sexual abuse, slut shaming, a woman’s right to choose, and the need for more consensual attitudes when it comes to sex, these erotic artists set about reclaiming and rewriting their own stories — using social media to share them. New York-based artist Natalie Krim, for example, began drawing ethereal, dreamlike depictions of female pleasure to reconcile a rape that happened in her teens. When she first started, the images straddled the line between child and adult as she tried to cling onto her innocence while claiming her own sexuality and power as an adult.

“As I have grown up, so has my work, but the need to express life in this very vulnerable way is still at the heart of everything I do. In the last three years my work has expressed the grief of my dad’s death, to my abortion, and most recently to a spiritual rebirth.” In capturing the commonality of the female experience she hopes she can “communicate a sense of acceptance of our fears, our desires, our struggles, and our triumphs. To celebrate our bodies and create a space that minimises judgement and encourages self expression.”

At the core of her drawings is female pleasure: orgasms, vulvas and breasts, masturbation and intimacy — the more we normalise it, “embrace it, write about it, create about it, fight for it, the more power we give to ourselves and women around the world,” she explains. “Pleasure is another space for us to champion our wants and needs and have our voices be heard. It is part of the larger idea of self worth, which is something I’ve struggled with even recently. When we say we deserve to experience pleasure, or we deserve to be financially independent, or we deserve love, or deserve to feel safe, we are creating a personal wholeness that says I am worthy. It’s all connected.”

Like many erotic artists, Krim posts her work on a personal Instagram account posing playfully beside her drawings. Sometimes she’s topless, other times she wears just her underwear and a pair of heels, inviting her viewers into her world and using her appearance for erotic and visual effect, but on her own terms. “This was a very clear decision I made the moment I first uploaded a topless photo of myself in 2011 that Rachel Cuccia took of me in Italy. I was declaring my body, my sexuality, my creativity, and my life.”

Canadian artist Nikki Peck, known to her followers as @Bonercandy69, is another illustrator who uses her erotic art to rewrite her own narrative: “I started drawing a lot of erotic depictions of female nudes because it was a way for me to almost embody this character, these positive sexual experiences.” Like Krim, her erotica was born out of her own difficult encounters: a series of toxic relationships which left her feeling gaslighted or slut-shamed. Peck wanted to feel confident, strong, and sexually charged, and her illustrations became a cathartic outlet for her.

They’ve since evolved into intimate scenarios of women that explore issues of rejection and shame in a very tongue-in-cheek way. “We are objectified for male visual pleasure, that’s just how it’s been since day one,” she explains. “Our sexuality is used against us and sold back to us in very hyper-sexual, derogatory, and violent ways.” Filled with humour, her work aims to flip that, establishing women’s place in pleasure and sexual exploration that’s as messy, hairy, and totally imperfect as it is in real life.

But Peck is fully aware of the challenges that exist when depicting sexually strong women without reverting to the male gaze. A term coined by cultural critic Laura Mulvey, who wrote in her 1975 essay “Visual Pleasure and Narrative Cinema” that, “the determining male gaze projects its fantasy onto the female figure, which is styled accordingly. In their traditional exhibitionist role women are simultaneously looked at and displayed, with their appearance coded for strong visual and erotic impact.”

With many different kinds of feminisms out there though, the commentary and discourse surrounding what’s empowering and what’s exploitative can be confusing. And Peck constantly asks herself whether women can self-objectify and still be feminists. “I can depict a woman as a sexually charged subject rather than as an object but that leads to questions about the viewer and if they get to see the woman as objectified, is that bad? What happens when a woman wants to objectify herself in say selfies, to reclaim agency over her body for her own pleasure? What if it’s her own desire to take that photo and if she feels sexy, why is that bad?”

Take Emily Ratajkowski, for example. She declared alongside a video of herself writhing in linguine for Love magazine’s advent calendar that “female sexuality and sexiness, no matter how conditioned it may be by a patriarchal ideal, can be incredibly empowering for a woman if she feels it is empowering to her.” A controversial statement that she’s been both praised and ridiculed for, some claiming that empowerment is not the same as feminism — especially when it still subscribes to heteronormative standards. “A lot of communities of feminists fight against each other because they think the others are silencing, erasing or problematizing what the cause is for,” adds Peck. “There’s a lot to understand and take in.”

For instance, second and third-wave feminists differ when it comes to aesthetic choices. Second-wavers rejected anything deemed to be patriarchal and demeaning like makeup and high heels. In 1968, they protested the Miss America pageant, where they threw away objects considered to be symbols of women’s objectification including bras, porn, and issues of Playboy. While third-wave feminists encourage women to embrace their sexuality as a way to take back their power, instead. They advocate for expressions of female sexuality and femininity as a means to challenge objectification, dismissing any restriction — whether patriarchal or feminist — that define or control how women should act, dress, or express themselves.

Sarah Whalen is more on board with the latter: she makes her work for herself and she likes “posting sexy pics on the internet” because it makes her feel good. “Obviously, I’m creating a version of myself, like a performance piece in the capacity that it’s viewed by others,” she says, encouraging a kind of voyeurism in her viewers, but one she’s totally in control of. On her Instagram account she breaks up her graphic black and white line-drawings with colourful photographs of herself naked or in her underwear, highlighting the tattooed flowers on her arms and the curves of her body.

Whalen’s erotic art started in her second year at a small arts college in Seattle, Washington when she made a giant vulva sculpture that was painted really fleshy with a gloss on the inner lips and lots of hair. “People were pissed,” she says. Even though a guy a couple of grades ahead took images of women with excessive amounts of plastic surgery from porn and ads, and ran them through a Xerox machine, distorted the body parts and painted them, everyone thought that was the cool and evocative. “For whatever reason the work I was making about women’s sexuality was not ok,” Whalen says.

This, she believes, comes down to America’s roots as a country founded by white puritans. Strict Christianity filtering into everything from abstinence education and victim blaming to the country’s strict abortion laws have made female sexuality a somewhat taboo topic. In the US, Whalen explains, “You have things like PornHub, which more people visit every single day than any other website on the entire internet basically, and then you also have Instagram taking down pictures of naked women.”

In fact, the artist has been censored by the platform’s strict community guidelines on more than one occasion. “I don’t know how the process works when it comes to taking things down but I think it’s sending a lot of mixed messages, when our culture is so hyper-sexual but only in this one type of way,” she says. “Removing things like erotic art that is a female expression of sexuality takes the soulfulness out of it.”

Yet for all its issues, the artists know that Instagram has given them the power to market themselves, explore the female body, reimagine sexuality and highlight a wider range intimacy than ever before. They’ve used it to celebrate a realm of sex and pleasure that is less one-dimensional, less shallow and less focused on the archetypal beauty made for the male gaze: female erotic art made by women who want to tell their own stories.