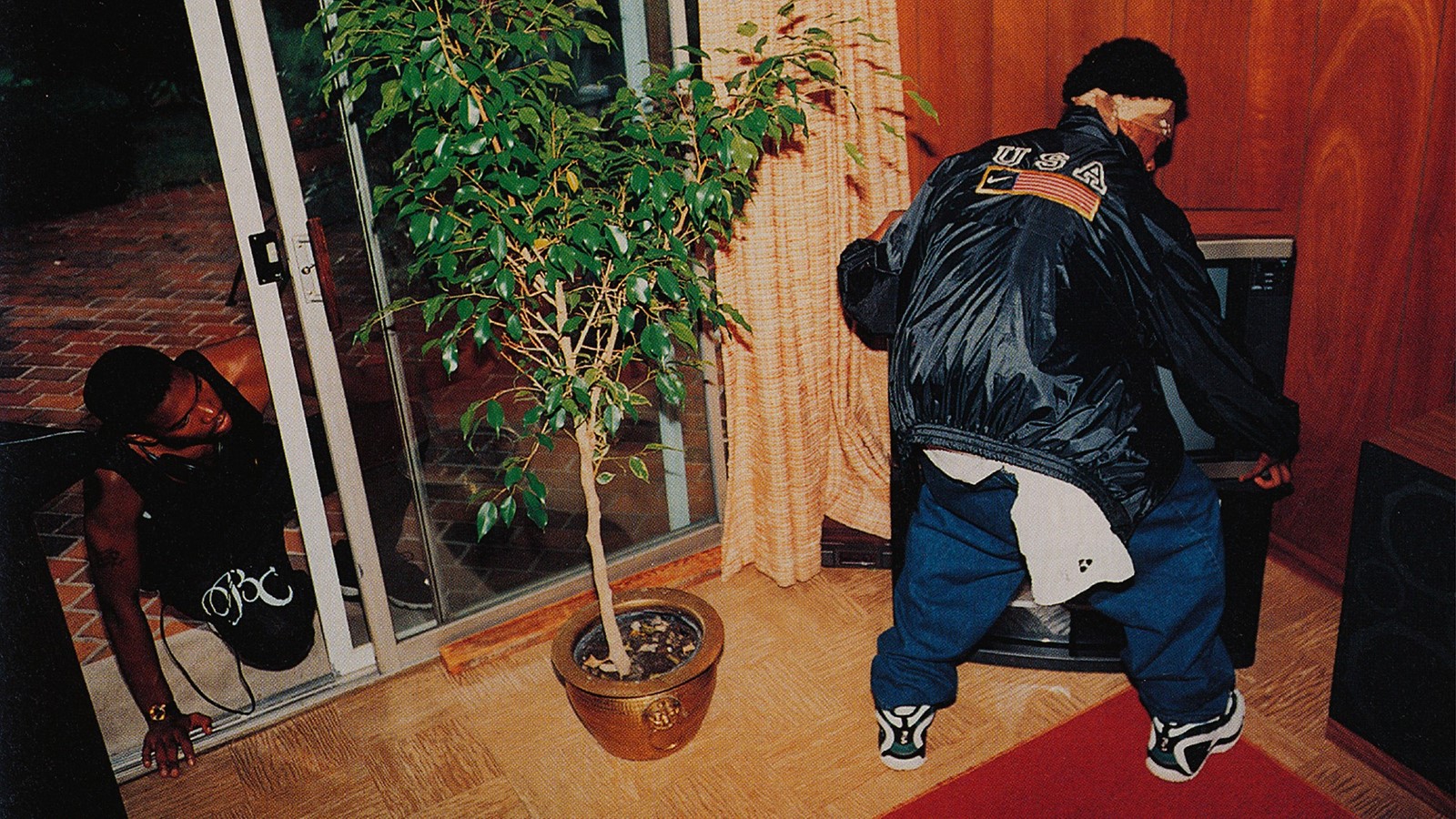

By 1994, Lower Manhattan was no longer the tip of an island slumping towards bankruptcy, as it was in the mid-70s, nor the plutocratic theme park it will later grow up to be. It was, instead, a uniquely diverse melting pot of identities, from the intensifying blur of Bowery and its pre-renovation lofts, to the Cantonese-speaking mom-and-pop shops around Mott Street, to the insistent corporate force of Wall Street.

Against this backdrop, 23-year-old Bernadette Van-Huy — a fresh-faced Queens native and Brown economics graduate — along with friends Antek Walczak, Thuy Pham, Seth Shapiro and Sonny Pak began throwing a series of parties at Club USA, the Midtown hub of ‘Michael Alig and the Club Kids’ fame. From this, the clique of downtown upstarts established Bernadette Corporation. The name was the opaque front for an art enterprise that, in the 25 years that followed, would cross the lines between party promotion, literature, art production and fashion with wild abandon.

Hard as it is to pin down what Bernadette Corporation (BC) ‘did’, the principle at the heart of the collective’s work was a belief that the historical ‘avant-garde’, with its lofty pleas for artists to live and create beyond capitalist infrastructures and logic, was obsolete. For the many ‘CEOs’ of BC, the increasingly universal corporate environment of 90s NYC offered a new frontier for subversion in art. Accordingly, over a three-year-stint, the collective turned to fashion, an industry with a reputation tarred in art circles for its superficiality, and acted out the behaviours typically associated with their high-rise-headquartered neighbours with disarming self-awareness.

“BC had no patience with the idea that artists could drop out of the capitalist system, punk-style, or resist it from some imagined outside position like 60s hippies,” Jason Farago wrote in The Guardian in 2013. “They called on young creative types to give up their fantasies of artistic autonomy, band together, and commit to working inside economic networks.” These are ethics best summarised by one of the many BC mantras: “Dress for work every day, keep regular business hours, and learn proper phone manners.”

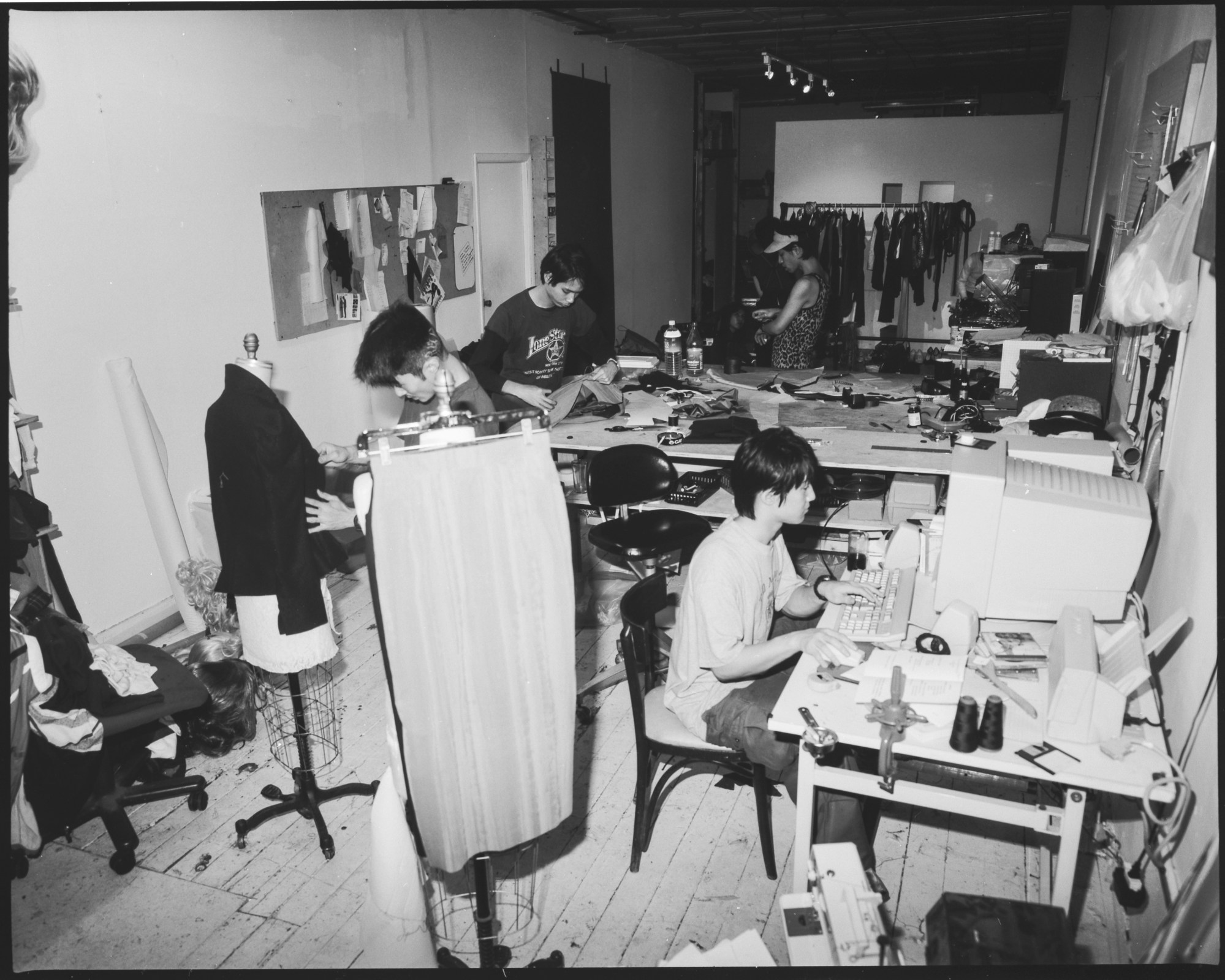

The supposedly transgressive spirit outlined above may seem rather empty: after all, aren’t we all simply what we pretend to be? Key to the ‘brand’, however, was the maintenance of an impassable boundary between their simulation of corporate practices, and the profit such practices typically generate. Effectively, they saw no shame in assuming the airs and graces of a company listed on the stock exchange while committing themselves to the lives of squatters. “Mock incorporation is quick and easy, no registrations or fees, simply choose a name [i.e. Booty Corporation, Bourgeois Corporation, Buns Corporation] and spend a lot of time together,” writes BC in Corporate Responsibility. “Ideas come later. The perfect alibi for not having to fix an identity, your corporate identity can be simply, “man, we’re a corporation.”” Further greying the boundaries separating ‘the young artist’ and ‘the corporation’, they even offer advice on inhabiting commercial property, a savvy move in an area where residential rents rise higher than the surrounding skyscrapers. “Though it’s not allowed, live there like your immigrant fathers. There is a chance you will get kicked out. If that happens, utterly destroy the space as you retreat in protest of the laws that tie the hands of big business.”

“I think the way Bernadette Corporation drew a parallel between corporation and youth cultural activity in the 1990s was not only brilliant, but prophetic,” explains Jeppe Ugelvig, the curator and fashion researcher behind ‘Fashion Work, Fashion Workers’, and author of a forthcoming book of the same title. “Fashion was not only a different space then; identity was. The corporatisation of both was happening at rapid speed, and its centre was downtown NYC. Transgression, critique, alterity, underground, all of these terms were in flux.”

The face of the city was being transformed beyond recognition. Boundaries that were once clearly delineated — art and fashion, tasteful and tacky, high-end and low-end, uptown and downtown — became muddled in some respects, and grew more distinct in others. The BC fashion label, straddling as it did the shifting tectonic plates of the cultural landscape, manifested this general precarity in a way that few could.

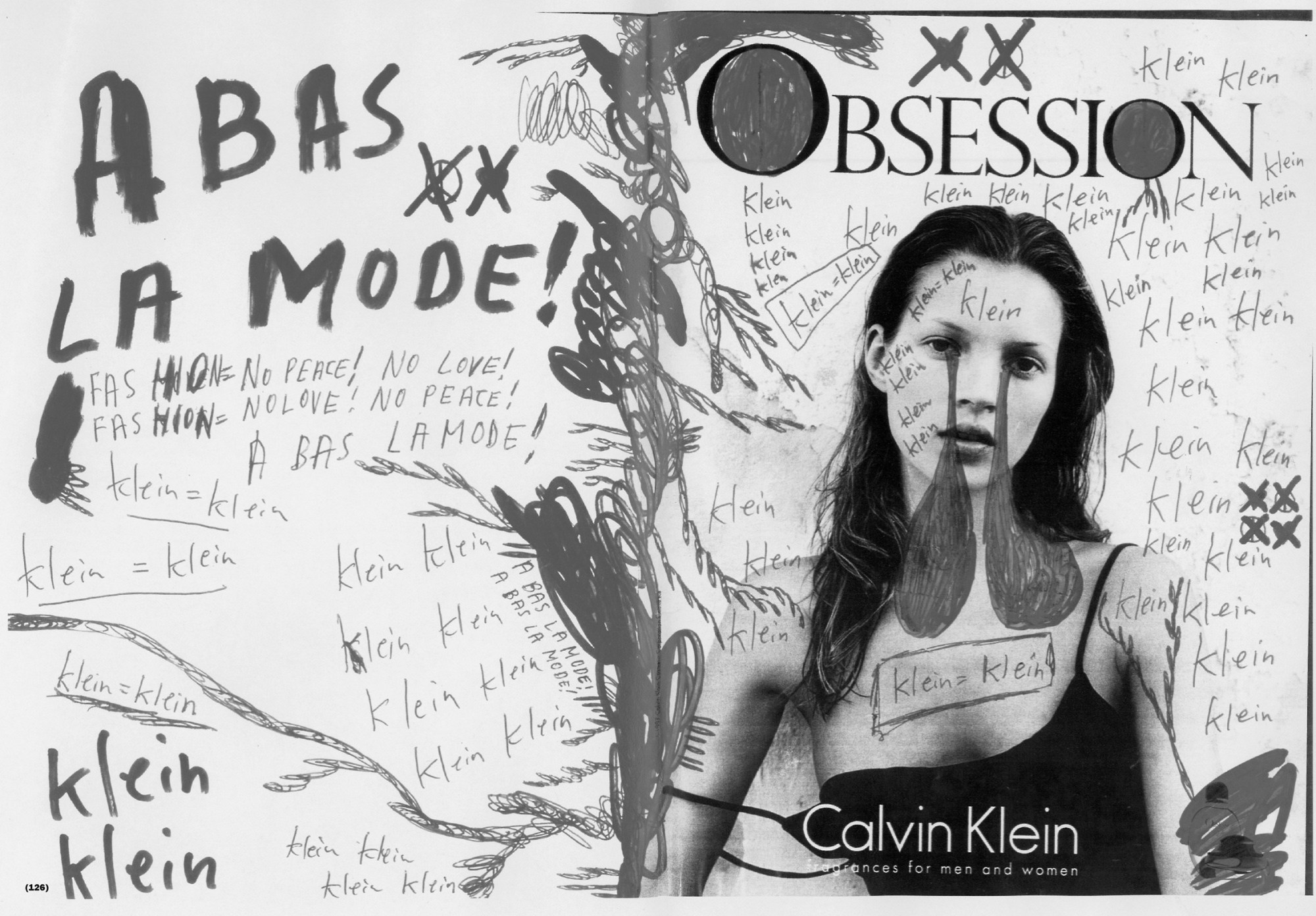

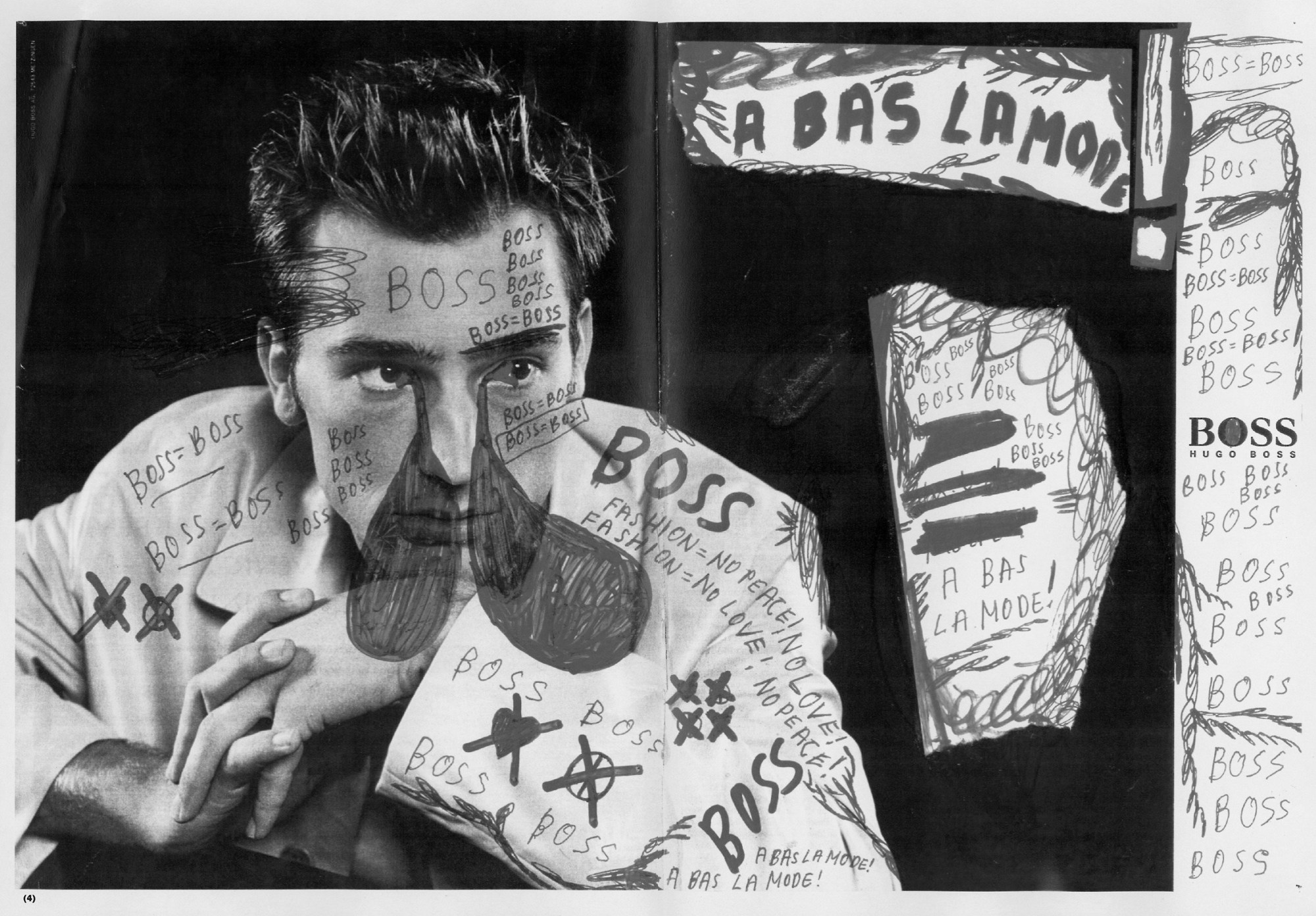

That said, though fashion may have been a different space then, its operational mechanisms were pretty similar to what they are today. Over the course of its three-year run, BC presented seasonal runway shows, regularly placed editorials in magazines from Purple to W to i-D itself, and even purchased ad pages in those magazines and many more. To put it simply, BC’s public face was orchestrated as if by a major house’s PR.

However, while the networks of image and identity distribution they adopted may have been orthodox, the result certainly wasn’t. In one case, the vapid, floral prose typical of a press release was supplanted by a jargon-spattered manifesto in the style of the Situationist International, and shows routinely amounted to parodies of stadium-worthy spectacles: one, for example, was outfitted with dancing bear mascots, cheer squads and fire cannons. They were, of course, nods to the excessive theatricality of the fashion show as a presentational format, but their genius lay in the simultaneous reconciliation and maintenance of a fragile duality: they were as sincere as they were tongue in cheek. Similarly, the garments on show also walked the fine line of fashion parody and praise, bringing together the Puerto Rican girls of the Bronx, sportswear, fur, and whatever was happening in the downtown fashion subcultures to which they had easy access. And then, in what reads as a bolshy two-fingers to anyone guarding the flame of ‘originality’ or ‘authenticity’, thrifted garments were routinely woven into the collections, cheekily branded with the BC logo.

There was a practical reason for their iconoclastic practice: “Only one person in the BC crew was an actual designer,” Ugelvig explains. “They had no skill, no money, no market, and all the members were under 25, so their re-use strategy was also born out of necessity. I think it’s also important to note that BC’s fashion mimicry had limitations, sometimes self-imposed,” he continues. “They resisted becoming an economically functional brand in a time when this would have been a possibility. The point was never to make money as a normal brand does, but rather to hysterically act out the presentational modes of fashion so as to explore their relationship to topics that were important to them, namely, identity.”

While we may be more familiar with big businesses inhabiting art spaces as a form of advertisement — just Google “UBS + art” — it was BC’s reversal of this that would prove its most enduring legacy, as a small-scale art collective adopting the guise of a large-scale corporation.

Take Vetements, for example, the semi-anonymous collective whose presentations of garments salvaged from the annals of cultural obsolescence can be read as a high-end mirroring BC’s thrifting practice. Reworked Levis; floral apron dresses in patent leather that mimicked your granny’s vinyl pinny; tourist slogan hoodies: these garments, paraded on runways in gleefully tacky Chinese restaurants, sex clubs, or under overpasses, land as jokes which are to be taken only too seriously — the price-point being the punchline. Just as BC did with their mining of downtown subcultures, Vetements openly revels in being far-removed from the rarified salons in which those presenting on the couture schedule typically dwell. At the same time, they are just as open about its status as a trademarked force, with CEO Guram Gvasalia explaining the tax-incentivised shift of its headquarters to dowdy Zurich or boasting of the brand’s supply/demand navigation strategies with clinical poise.

Even more brazen in its BC-esque identity performance is Demna Gvasalia’s Balenciaga. Owned by Kering, one of the world’s largest luxury conglomerates, the intrigue here lies in the brand’s ability to openly capitalise on being part of such a far-reaching corporate empire, rather than resort to the masking narratives of uniqueness and artisanal craftsmanship typically employed by, say, Chanel, Hermès, or Louis Vuitton. With its concrete-grey background and geometric, sans-serif script, even the logo issues a shout of conglomerate pride.

“I’m actually quite intrigued by Gvasalia’s work at Balenciaga,” ponders Ugelvig. “The Kering logo T-shirt, the WFF T-shirt following immediately after, the revival of the 80s business silhouette, past logos… it’s pretty clever, stylish, historical, and sometimes dark.” Indeed, the new Balenciaga aesthetic has often relied on marketing what amounts to corporate away-day merch, flogging upgraded ‘hacks’ of laundry and paper shopping bags, and even going as far as to usurp others’ logos, most notably that of the electoral campaign of famously anti-big-business Bernie Sanders. “It’s amazing and scary that the ‘real’/millennial/corporate fashion industry has picked up exactly the same tactics as BC — playing with branding — as a way to distinguish themselves in the market.”

Ugelvig’s comment above is, frankly, the clincher. BC’s frantic exercise in corporate branding had significant self-imposed limitations — most importantly, holding back from full participation in the fashion system by refusing to monetise it. Their strategy, for all intents and purposes, was a means of distinguishing themselves both from and within the art space. Now, however, we are bearing witness to brands indulging in similarly extreme self-aware demonstrations of brand identity, only with the barrier to squeezing a profit removed. This, arguably, is what positions the mentioned brands, among many others, as credible ‘heirs’ to the evolved BC legacy. “We’re now living in a corporate era of fashion, much more global, asphyxiating and catastrophic than the independent 90s that BC’s cleverly but also quite naïvely commented on,” Ugelvig concludes. “Independence is no longer a position in fashion, which is why I think Gvasalia’s commentary-from-within is interesting to follow: what are its limits — and what are its unique possibilities exactly because it is an actual corporation?”

Let’s think back to Balenciaga’s phone number shirt from spring/summer 19: ring the number, and you’re asked a series of pretty inane questions before abruptly being hung up on. In the hands of BC, this might have read as a fittingly gimmicky playing-out of how corporations collect data, the most valuable commodity of today. In the hands of a Kering-owned company, it reads similarly — but the brand’s corporate backing necessarily invites a reflection on if, or rather how, such information could be used to reach the end-goal of turning a profit.

Whether it’s actually being processed by some big data cruncher is pretty irrelevant: the point is that this act of ostensibly sincere meta-commentary generates interest and that interest generates sales. Yet it doesn’t read as sinister, but rather as witty, or even funny. As Chris Kraus wrote in Where Art Belongs [2011], BC “state[d] the obvious in all its complexity,” refusing to offer a transcendent answer to, or critique of, what they observed. They held up a funhouse mirror to a world in which identities, personal or social, creative or corporate, were growing indistinct at the margins. 25 years on, brands from Vetements to Balenciaga and beyond are doing the same — but in a world where these factors have inextricably merged.