This story was originally published by i-D UK.

Hilton Als was going to call the exhibition he’s curated of Alice Neel’s works — displayed first at David Zwirner in New York, and now just opened in Victoria Miro in London — Colored People. Hilton is best known for a book he wrote called White Girls. There’s a nice symmetry there between Colored People / White Girls. The title they settled on in the end, Uptown, feels less loaded and polemical, definitely safer, but in a way, it works. The open, matter-of-fact place and time specifics of Uptown says a lot without really saying anything.

Colored People, though, well what a title that would’ve been for an exhibition of Alice Neel’s Uptown paintings. How much to ruminate on. Satirical? Angry? Offensive? It’s definitely, at least, doing something, with that outdated phrasing, the way it carelessly lumps together all of Alice Neel’s sitters into one homogenous group.

But for anyone even a little au fait with Hilton’s work as a writer and his wonderful way with language, well, you can sense that celebratory reclamation in the face of the language of oppression as easily as you sense the bridling anger at the oppression itself. A little sleight of hand in the way it draws attention to such repressive language, while opening the broadness of the “colored people” to become something expansive, rather than stifling.

Manhattan’s Uptown, in Alice Neel’s time, was not the place to be if you were an artist. She moved there from Greenwich Village in the 30s, and lived and worked in Spanish Harlem and the Upper West Side until her death. During her lifetime she was unknown, unloved, and unappreciated. She was a figurative painter in the glory years of abstract expressionism. A woman during that epoch of unbridled white male artistic ego. She was a woman who lived in an unfashionable part of town and she painted “colored people.”So yeah, she was poor and unsuccessful and died basically poor and unsuccessful too, even though, by the 70s, she was finally getting some respect. It was, as it usually is, too little too late. She died in 1984, and of course the same people who would’ve ignored her then, venerate her now.

“Had Neel restricted her canvas to the white world, she would have been celebrated sooner, swear to God, because then her detractors, or the people who ignored or marginalized her, would have seen themselves, which, in the art world at least, is always rewarded,” Hilton writes in the exhibition’s catalogue. “That wasn’t who Alice Neel, artist, was though. She did not treat colored people as an ideological cause, either, but as a point of interest in the life she was leading there, in East Harlem and beyond.”

Alice was born in 1900 into boring middle class Americana. Her life was touched by the tragedy of those who try to escape boring middle class Americana into bohemia; death, poverty, penury, communism, lack of recognition, bad husbands, bad boyfriends, and bad lovers. One boyfriend burned a load of her works into a cinder. There were nervous breakdowns and attempted suicides. Her first child, a girl, died at 11 months old. Her second, also a girl, was abducted by her Cuban husband and Alice never saw her again. She had two more — two boys from two different fathers.

In the 70s she started to get a little bit of recognition, and had her first big retrospective at the Whitney in 1974. She was hardly famous, though, when she died. She still lived in the same apartment. Inhabited the same milieu.

It’s easy enough for these facts of biography to cloud our judgement of her painting, but instead the paintings are resistant to such dull, maudlin, romantic-biographical interpretations. They thrive and thrill in humanity, in the face of Alice’s personal devastation, and the sociopolitical devastation of those impoverished, ignored places in New York she worked in and captured on her canvas.

I stumbled into this exhibition out of the rain, in New York in April, at David Zwirner’s downtown Chelsea gallery. I stumbled, somehow, dripping with water, into an ostentation of resolutely UES late-middle-aged women of the fur clad, thickly painted faces and dyed hair variety, on a guided tour of the work. They’d come from a very different kind of uptown to the Uptown Alice painted. And couldn’t in a way, have better shown the disparity between Neel alive, struggling, and Neel dead, flourishing. After the exhibition, I was encouraged to revisit Hilton’s book White Girls, and it’s easy to see, reading those essays again, what attracts Als to Alice’s work. Political outrage, cultural outsiderness, love of humanity, resistant to reduction. He writes, of a 1943 work, Julie and the Doll, “Alice Neel’s paintings fight against the status quo’s determined stance to forget the living whom they feel contribute nothing to their lives, even as they make so much life around them.” And it might well stand as a mantra for his own work.

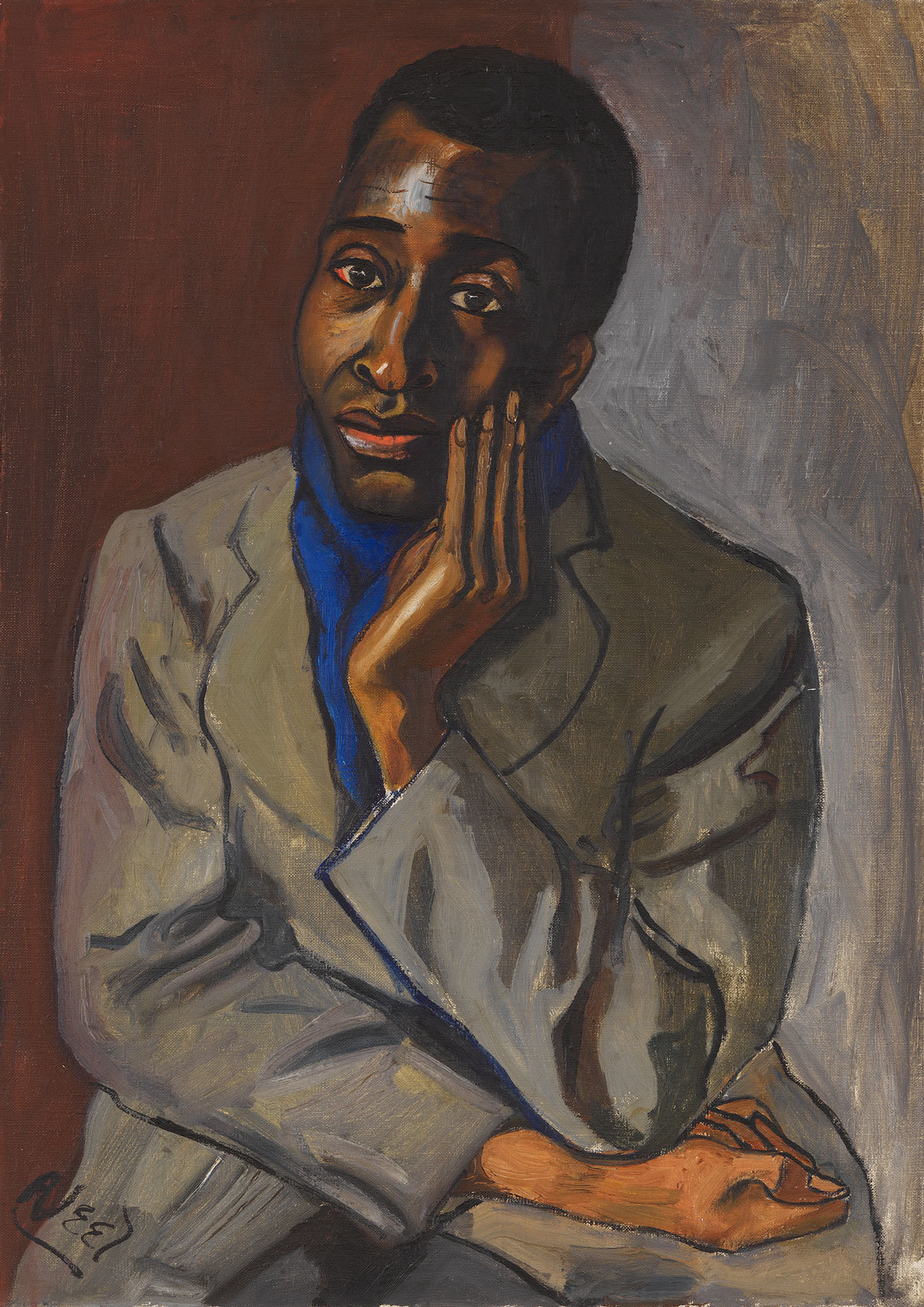

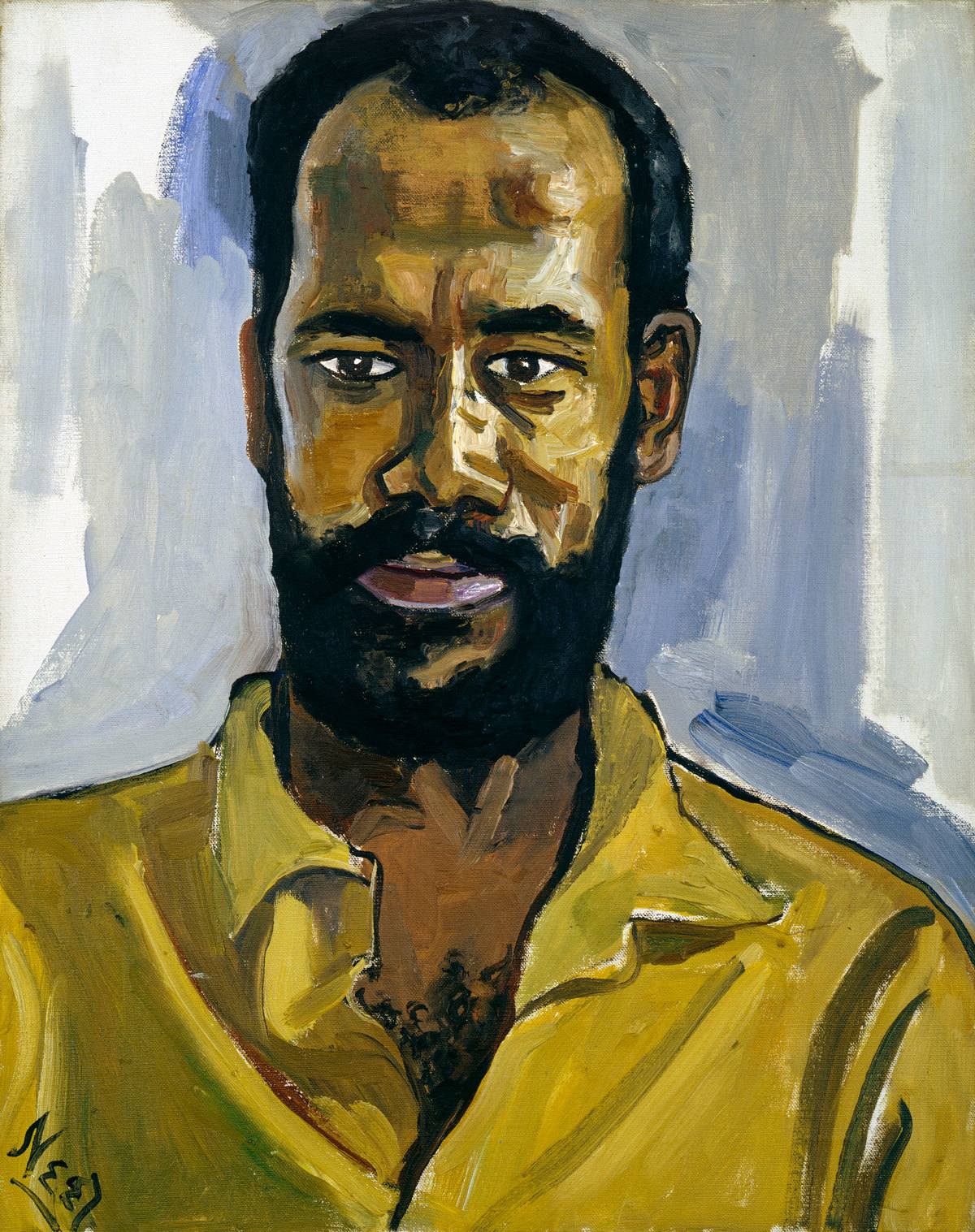

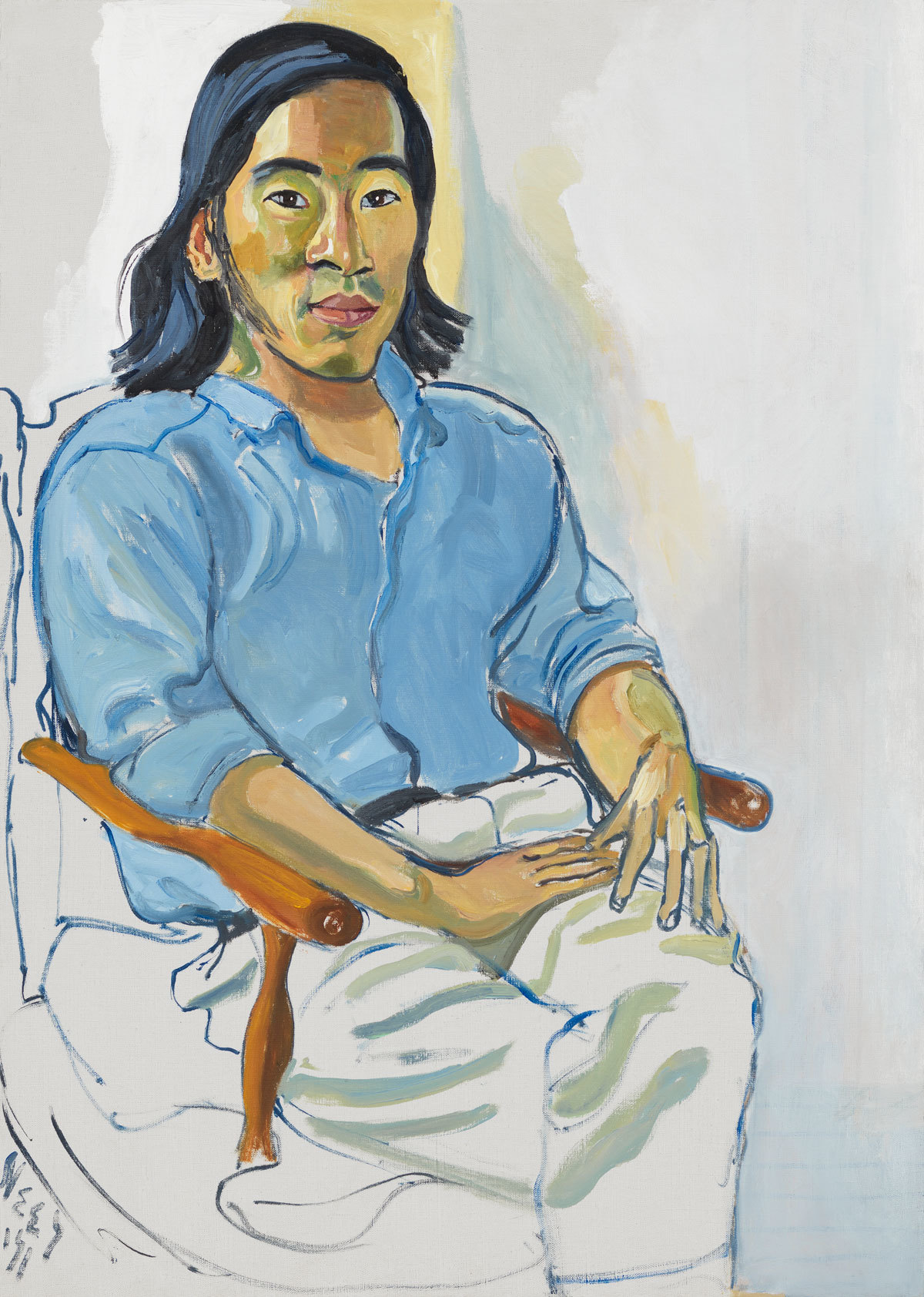

So, those paintings. First, they are paintings you can’t help but love, paintings that capture a strange beauty, a feral honesty, they have a rugged simplicity, an enveloping humanity. They are paintings of people who flitted through Alice’s Spanish Harlem house and sat for her.

And how easily you could imagine, too, the young Hilton, finding himself in Alice’s studio, sitting for a portrait, part of her world. Als and Alice figure as opposites and shadows and cracked reflections of each other; arriving at the same place from very different starting points. The gay, black, New Yorker writing about White Girls. The white, straight, country girl painting Colored People. They are hardly post-racial in the way their work uncovers some shared humanity, but there’s an optimism there to not allow race or gender to limit yourself, even if it’s unavoidable, in reality, in the world we live in. Even as other people limit you because of your race or gender.

The exhibition covers so much, it’s hard to find a place to start. Hilton or Alice? Race or gender? New York or America? Now or then? Harlem or the Upper West Side or the Chelsea gallery scene today? The paintings or the painter or the people she painted? There’s an exhaustingly near infinite set of matryoshka dolls to unpack. Each doll a different outsider; youths and street kids and immigrants, black intellectuals, and activists.

Then Alice herself, an outsider to the art world with a Puerto Rican lover, a white girl in Spanish Harlem. All this apartness is enough to break your heart, but only because Alice’s paintings transform such tragedy into such majesty. She preached no sermons over their bodies. She created paintings that were tributes to the sitters, not the painter.

Georgie Acre, for example, a boy she painted multiple times in the 50s, whose growth and changing personality she charts, from scampish street kid, to adolescent posing, world-weary late teenager, in one painting he poses with a knife. Does it change our feelings about these paintings if we know, twenty years later, Georgie ended up in prison for murder? There’s a fascination in the masculine pose afforded by Georgie, which Alice captures so well. All those proportions so slightly off. The eyes a little too big, looking at us a little too closely, cloud everything.

But not just a chronicler of the uptown underclass who made her home their sanctuary, she painted the academics, poets, playwrights, activists, polemicists, and campaigners. Her work is a portrait of the life and lives of Uptown. Alice Childress and Harold Cruse rub shoulders with unnamed sitters, ordinary “colored people” given ordinary, descriptive but universal titles; Spanish Woman, Black Spanish-American Family, Three Puerto Rican Girls, Two Puerto Rican Boys, Mother and Child, etc. They chart a changing world in their sitters’ hairstyles and fashions and postures.

My favorite image by Alice Neel is of a young boy called Benjamin. One of the latest in the exhibition, painted in 1976. It’s so resolutely simple, yet so massive. Benjamin, a youngish black boy. His blue rollneck on a blue background. Big, beautiful, almond-shaped eyes. One eyebrow arched. It’s so simple and complex and just full of a humanity you can’t describe at all. A Mona Lisa of Upper West Side.

Hilton, in the catalogue, imagines Alice’s thoughts as she paints Benjamin. And it seems as fitting a place as any to end on, to sum up both Hilton and Alice together. “Love comes in many forms, and I love you, now, while I’m painting you. That love has a certain intensity while I’m painting a person, and it may not last past the painting, but at least the work’s a record of that love. My paintings are a way, sometimes, of trying to understand how we get into another person, and why, and why it’s beautiful, hard, exhausting, enriching. People — that’s all we have, one another. And sometimes that’s unbearable, and sometimes all we crave.”

“On the third or fourth day he came to sit,” Hilton imagines. “She invited the boy to take a look at what they had done together. He did. And he was amazed and then shy and then amazed again because there he was.”

Credits

Text Felix Petty

All images Courtesy David Zwirner, New York/London and Victoria Miro, London © The Estate of Alice Neel