Without access to basic art supplies, inmates have long innovated new modes of creative expression — and that was the case for whistleblower Chelsea Manning. For the last two years of her seven-year sentence, while incarcerated for her involvement with WikiLeaks, Manning was working on her own “DNA portraits.”

On August 2, these portraits will be on view at Fridman Gallery in Manhattan, in Manning’s first exhibition, A Becoming Resemblance.

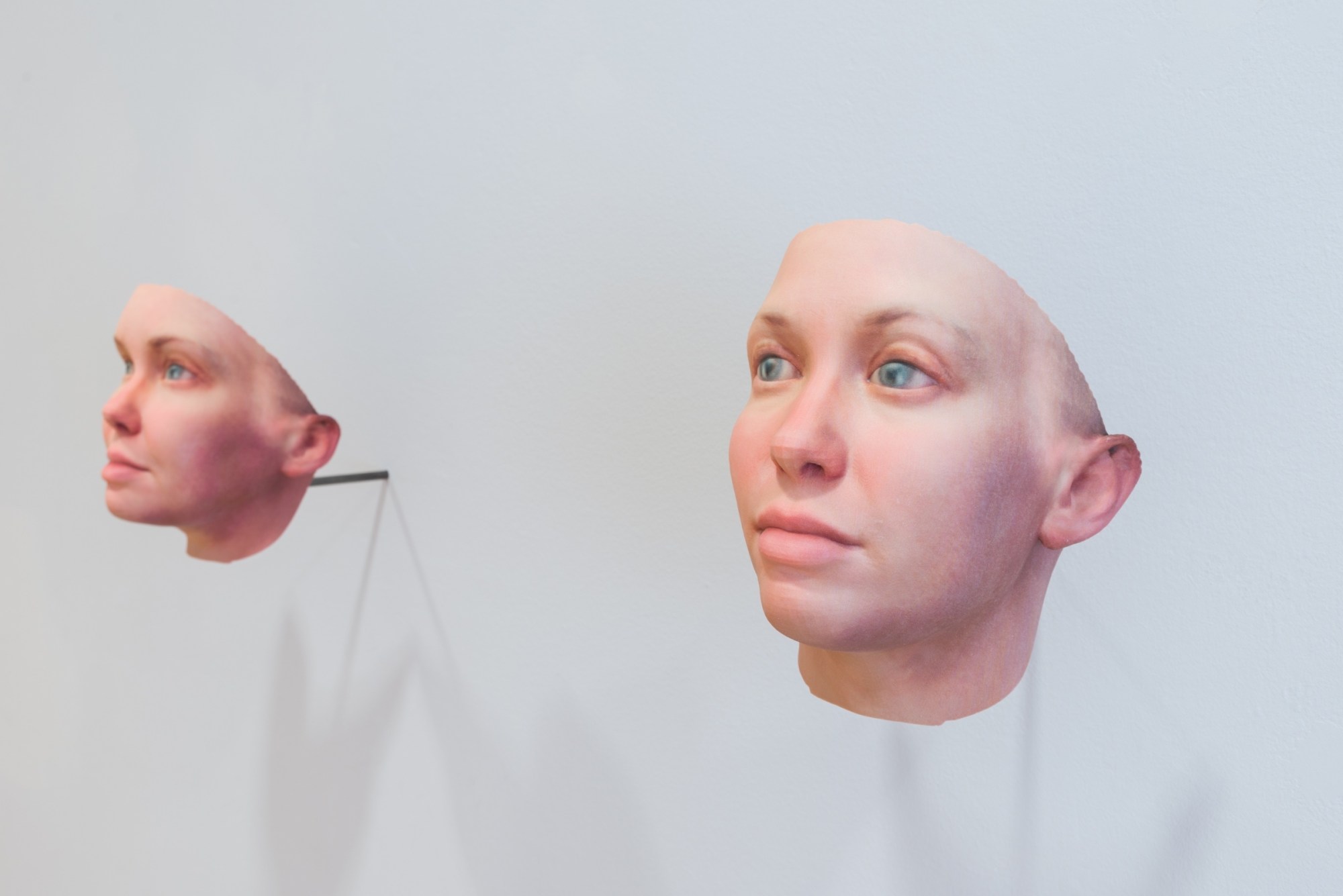

The show comprises a series of 30 3D-printed portraits of Manning created in collaboration with Brooklyn-based artist Heather Dewey-Hagborg. It’s an exhibition that explores “genomic identity construction and our societal moment,” Dewey-Hagborg told i-D.

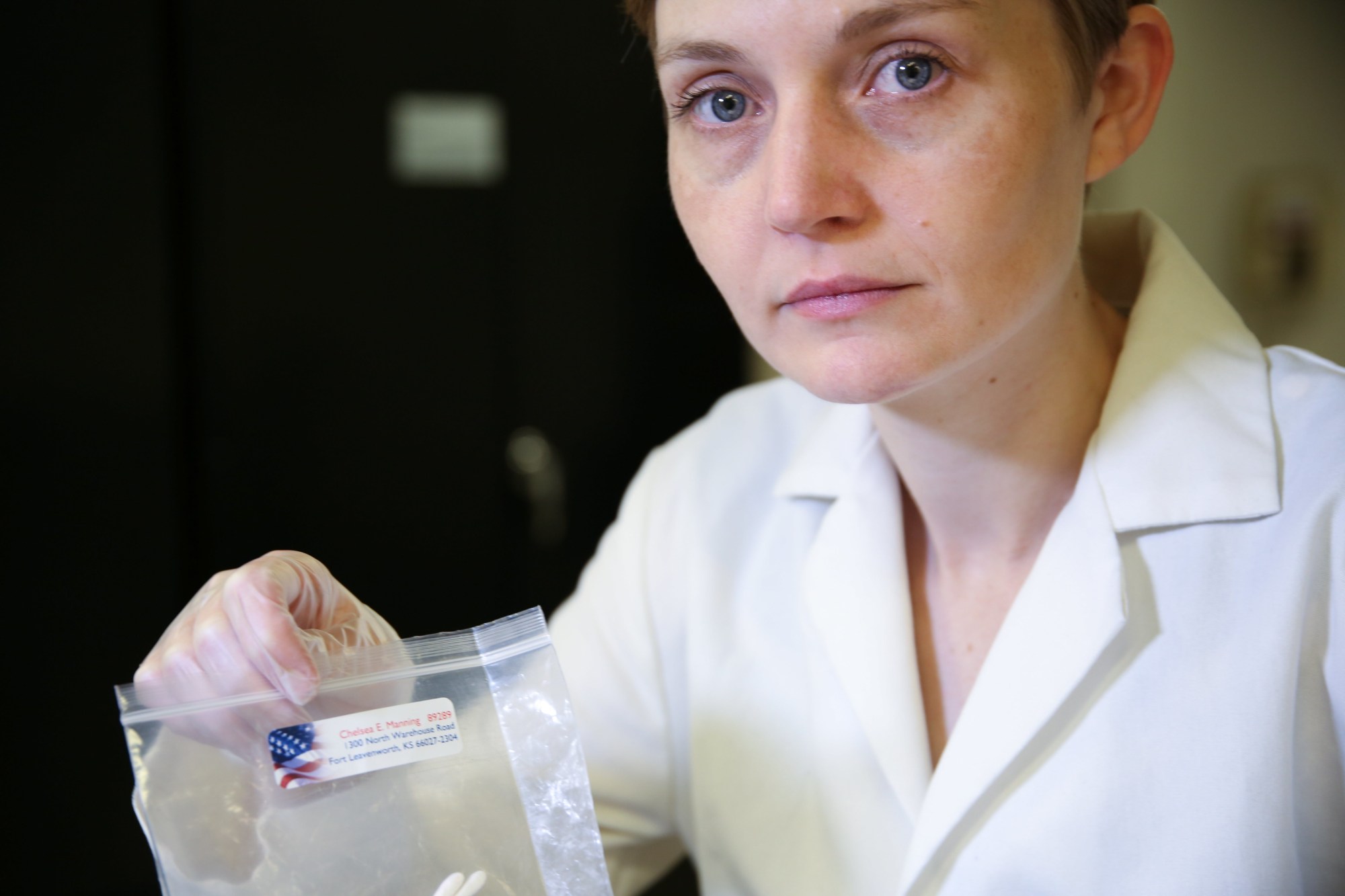

In other words: These portraits of Manning were not painted in the traditional sense. They were made from the DNA found in Manning’s hair and cheek swabs which were mailed out of prison.

Dewey-Hagborg can’t comment on whether getting the DNA swabs out of jail was difficult or not. “I wasn’t there, but as I understand, Chelsea gave them to her lawyer who visited her at the prison,” she said. “I am not aware of any difficulties.”

It sounds like an incognito process, but there’s nothing really to hide. Dewey-Hagborg has previously made 3D sculptural portraits of strangers by picking up their cigarette butts, as well as pieces of gum and hair found on the streets of New York. (It’s amazing to think humans shed roughly 50 hairs a day and there are 108 nanograms of DNA in a microliter of saliva.)

“What can I learn from someone who has left a piece of themselves behind?” is the question behind Dewey-Hagborg’s work.

The idea for this exhibition began in 2015, when the artist was contacted by Paper magazine. The publication wanted her to create a DNA portrait of Manning to accompany an interview it was doing with the whistleblower. The only image of Manning available at that time was a black-and-white photo from 2010. Through letters and Manning’s lawyer, Manning and Dewey-Hagborg corresponded to create the show together.

Manning went through her gender transition behind bars and her image was not made public from 2013 until she was freed on May 17, 2017, after Barack Obama commuted her 35-year sentence. Manning was visually silenced, in a way, and Dewey-Hagborg attempted to give Manning back her image while she was in prison. “It’s a form of visibility, a human face she had been denied,” Dewey-Hagborg said.

The development of the series helped give Manning a voice in a time when she didn’t feel like she had one. “Prisons try very hard to make us inhuman and unreal by denying our image, and thus our existence, to the rest of the world,” said Manning in a statement. “Imagery has become a kind of proof of existence. The use of DNA in art provides a cutting edge and a very postmodern — almost ‘post-postmodern’ — analysis of thought, identity, and expression. It combines chemistry, biology, information, and our ideas of beauty and identity.”

Dewey-Hagborg created 3D printed portraits from Manning’s DNA by hacking a piece of technology called a “morphable model,” which makes 3D faces based on biological data. The particular machine she hacked, which comes from a university in Switzerland, developed the portrait of Manning by correlating DNA and a 3D model of a face. “It looks at things like sex, ancestry, eye color, hair color, freckles, lighter or darker skin, and certain facial features like nose width and distance between eyes,” she said. “The program I wrote is taking a model usually used for identifying faces and making it a face-generating model.”

But it wasn’t all science. Artistic additions, like hair and face alterations, were made to complete the artwork. Dewey-Hagborg usually outputs five or 10 different versions of a person’s face and then chooses one she “thinks is most compelling, subjectively,” she explained. “In Chelsea’s case, for her original portrait, I created two models, one androgynous and one gendered ‘female.’ The point was to call attention to genetic reductionism and the algorithmic stereotypes of what a gendered face might look like. What could algorithmically ‘female’ even mean?”

While the portraits gave Manning back a form of visibility, the meaning of the work has changed now that she is free. “She still hasn’t seen the 3D-printed pieces in person — this exhibition will be the first time she gets to see them,” said Dewey-Hagborg.

The project is symbolic: it shows just how many ways your DNA can be interpreted, or read as data. But it also engages with the uncertain future of DNA surveillance. “Our genomic information, along with many other bodily forms of data, will be increasingly legible,” said Dewey-Hagborg.

“The question is who will have authority over its interpretation? These will always be ambiguous, subjective traces and the exhibition attempts to really drive this home.”

‘A Becoming Resemblance’ is on show at Fridman Gallery in New York from August 2 to September 5, 2017.

Credits

Text Nadja Sayej

All images courtesy of Fridman Gallery