Perhaps you recently witnessed a major fashion label release an advertising campaign that reeked of racism and had a vile, colonialist attitude. The kind of brand that built its name around celebrating the traditional family unit and thin, beautiful, cis-het, white people. Maybe you had already bought into this brand, and post-scandal, when others were calling out their behaviour and vowing to never shop from them again, you shrugged it off. You still liked the brand, you liked their vision, and showed that continuing allegiance by engaging with their content, by liking their posts, maybe even buying something in the sales. In doing so you sent out signals, not just to your friends and followers, but to those who own your data. And maybe those signals will be used to target you with articles that subtly play on your fears about job instability due to an influx of immigration.

This hypothetical interaction between fashion and the political sphere that fashion-trend forecaster turned whistleblower Christopher Wylie was discussing late last week, during a talk at the Business of Fashion’s Voices event. Wylie came to the world’s attention in March of this year when, via an investigation by The Guardian, he exposed the unauthorised use of more than 50 million people’s Facebook data by a secretive data firm called Cambridge Analytica — where he had worked — whose clients included Donald Trump and the Brexit Vote Leave campaign. The firm used this data as a political weapon, to help sway elections in favour of their clients. The information gained via Facebook was used to build personality profiles, and exploited the ‘’inner demons”, according to Wylie, of those people profiled, playing on their potential biases. To the ordinary individual who feels they have nothing to hide, on a personal level it can be easy to brush off concern about your personal data being bought and sold by companies that seem to have little bearing on your life. Yet what the Cambridge Analytica scandal brought to the surface, is that your data is worth protecting if you value democracy.

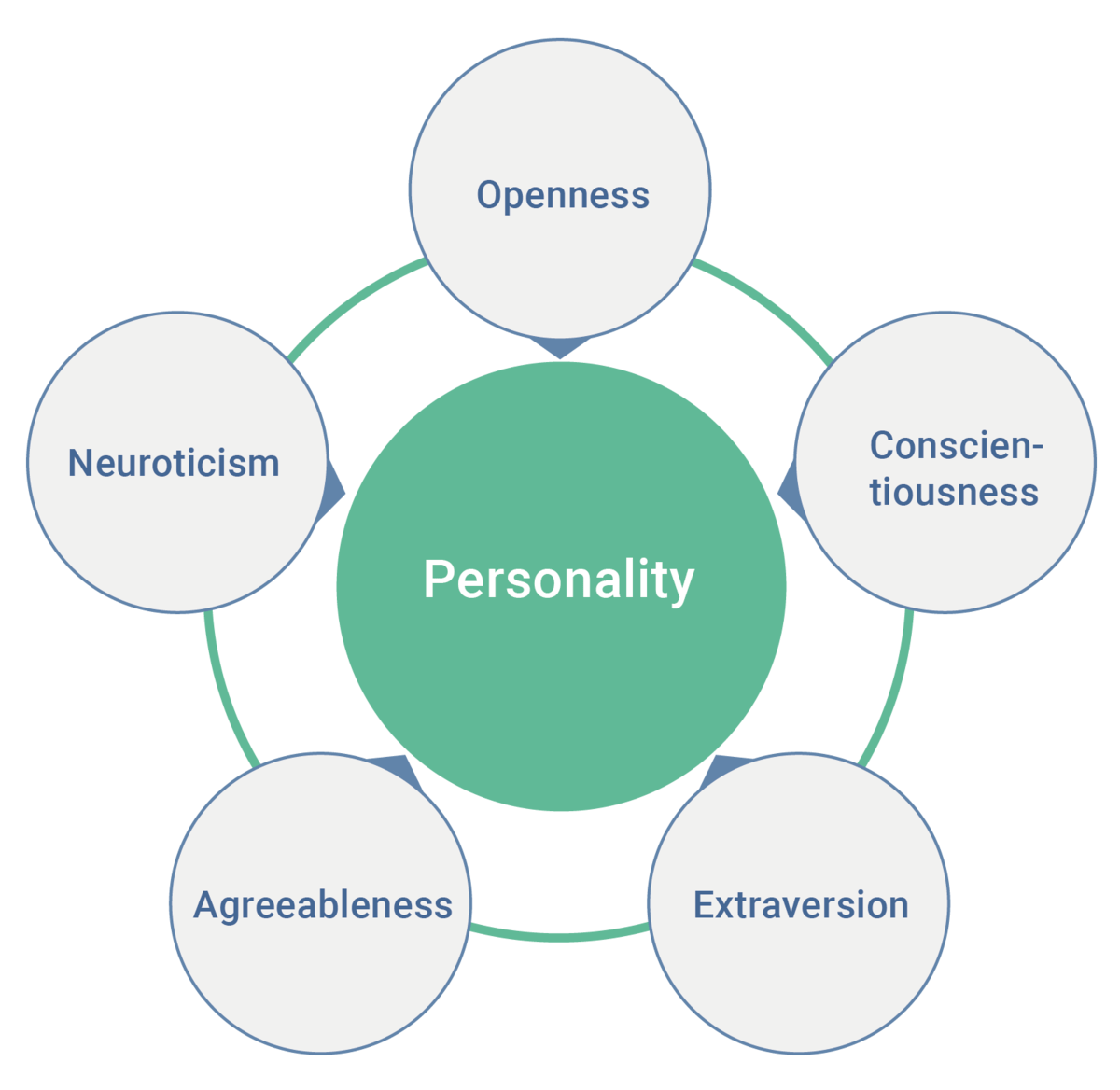

In Wylie’s recent talk he expanded on the ways in which the dodgy data firm repurposed the tenets of fashion trend forecasting in order to influence political outcomes. As Charlotte Gush wrote earlier this year, “Understanding the mechanics behind a sea change in taste, as the fashion industry attempts to do on a ever-shortening ‘seasonal’ basis, helped Wylie mastermind a sea change in voters. You can’t — effectively — tell people what to like or wear (or indeed who to vote for), but you can show them, over and over and over again, with repeated messaging that is meaningful to them and has a cumulative effect.” Personality traits, Wylie explained, are being identified and exploited for political ends, and cultural narratives created by fashion and other creative industries are increasingly becoming targets for those seeking to gain power. Cambridge Analytica developed a brand matrix, mapping consumers using the ‘Big Five’ personality traits — openness to experience, conscientiousness, extraversion, agreeableness, and neuroticism. So LL Bean, an American brand with a traditional, wholesome, predictable and practical vibe to its clothing and branding is going to have customers who are less open to new experiences and rate highly for conscientiousness, a trait associated with being more conformist, systematic and disciplined. The LL Bean customer is much for likely to be conservative politically than say someone who wears, or is a fan of, Charles Jeffrey, or in the example Wylie gives, Kenzo. An LL Bean customer can be identified and fed information that can play on their personality traits, for example exploiting their fears of disorder and change.

Fashion tastes, as Wylie explains, are particularly suited to analysis, allowing data firms to easily build profiles of sections of society who they can then target them with certain messages. Fashion is so closely tied to our identity and such a prevalent part of our everyday lives that it allows us to constantly send out signals into the world about our status, our desires and beliefs. This is true for everyone, not just for those who consider themselves followers of fashion. We use it to express ourselves, but also to tell other people something about who we are or who we want to be. And our ideas about what fashion says about us are largely constructed by the narratives put out into the world by brands. Even if they don’t impact you on an individual level — even if you don’t particularly care about what a certain brand is saying — you are still part of a shared cultural understanding about what that brand means to those who wear it, and how they are intending to be viewed — and how others likely view them.

We used to primarily send out these fashion-signals in the real world, but now much of our identity performance happens online, where we constantly broadcast our brand alliances, our celebrity influences, our taste. The internet has exploded the fashion industry, taking it from the cloistered preserve of a few, to an easily accessible, endlessly consumable part of daily life — it is an incredibly powerful industry worth 2.4 trillion dollars last year. This sharing of our lives online has also made data collection very easy. Sometimes we do it wittingly, though often not.

It seems lately that fashion designers have felt the increasingly connections between their industry and the political world. Fashion has always reacted to the times in which it is in, but as the industry has become increasingly accessible through the internet, the messages go further than ever. There is a new gravitas to fashion, perhaps in part because the industry has been forced to grapple with its own darkness in a way that it hasn’t had to previously, due to the prevalence of social media: from #MeToo to racism and the industry’s position as a major contributor to climate change, fashion is waking up to its resonance beyond the catwalk, and its front and centre position in the culture wars.

Globally, people are engaging with fashion more than ever, at the same time, data is becoming a driving factor in daily life and just about everything can be reduced to easily rankable numbers. So we are able to compare ourselves, constantly and immediately, to others in an unprecedented way. We need to create a sense of status that has to be constantly maintained through our clothing, the events we attend, the places we travel to — our tastes that we broadcast into the world from our social media accounts. In this way too, fashion has been elevated in importance in our everyday lives. “Many people feel they are having to work harder than ever to defend their status affirmation signals,” writes Steffen Mau in his forthcoming book The Metric Society. Clothing is a highly visible route to status.

The premise of Wylie’s talk with BoF, and his follow-up discussion with the FT, was to tell the fashion industry that they need to think more clearly about their brand messaging, to acknowledge and examine how they shape culture, beyond getting millennials and Gen Z to engage with their product and become customers. Not just to correct past errors of racism, sexism and body-shaming, and the way they luxury industry has created unachievable goals and a constant push for material prestige. He is saying that fashion has a responsibility to protect democracy. “The thing that really frustrates me is when you’ve got people separating citizens and customers as if they’re different people,” Wylie stated. “They are the same people. And there are brands that are popular among people who are starting to engage more and more with the alt-right. Where they are perfectly positioned to begin a conversation with their customers about what’s happening in society.”

Essentially, fashion brands must recast themselves not just as selling products, not even just as selling ideas around a particular lifestyle, but as selling equality, openness, social justice. And it needs to go deeper than slogan T-Shirts worn by occasional activists starring in campaigns.

“When we talk about the need for diversity and representation of minorities or people of colour –– so that a black person or a lesbian or a person in a wheelchair can see themselves in the narratives you create… we talk about it as if that’s the value,” Wylie said in his Voices talk. “We are past that point… We need you you guys to do a better job at cultivating our cultural narratives for our own national security and for the preservation of our democracy. The shame, the colonialism, the racial biases, the toxic masculinity, the fat shaming… is exactly what Cambridge Analytica sought to exploit.” So what are brands supposed to do? How can they use their power to affect political thinking? It’s very, very hard to change someone’s mind politically — political opinion is formed through a complex confluence of factors including family background, religious beliefs, geography etc. But if fashion can influence what we value and how we feel about ourselves and those around us, it can reshape the cultural narrative through making diversity a mainstay of its messaging. If the industry can move away from, or even actively deconstruct narratives that cultivate insecurities and exclusion that play into social hierarchy, if it can seek to dismantle stereotypes in a genuine way, then fashion intertwining with politics can be a force for good.

Fashion is powerful, fashion shapes ideas. And so it can help to reshape ideas, collective knowledge. Brand messages may not change the mind of an individual, but they change our shared cultural understandings.

It’s a big ask for an industry increasingly grouped into larger and larger corporations — one driven by the need to shift vast numbers of product and built on selling aspiration tied to materialism — to be willing to shoulder some of the responsibility for a free and open society. But clearly, the cost of not evolving towards a new mentality will be high.