In the midst of a business park in Bedfordshire, you’ll find Yarl’s Wood Immigration Removal Centre. Slotted in amongst the stocky offices of cement and the tall street lights that curve ominously towards the sky, you’d be forgiven for not noticing the 400 women that live between them; you weren’t meant to.

Across Europe, our governments routinely detain asylum seekers with the hope of removing them back to their ‘country of origin’. Out of all of these, Yarl’s Wood, operated by Serco, is perhaps one of the most notorious. The women are not held for having committed any criminal offence, yet they are left to wait indefinitely for the outcome of their asylum cases. Despite allegations of sexual and verbal abuse by the guards, and being labelled ‘a place of national concern‘, access remains rigid and almost impenetrable. When I went inside, I wasn’t even allowed to bring a scrap of paper with me, and phones, or any video recording devices, are strictly prohibited.

Then, in the dead of night, people are deported. As one woman told me, “We are constantly living in a state of fear. There are so many planes, we never know if we will be forced to leave”. Others have said how they have seen women taken half-naked, their heads covered by blankets and chained by several guards. The severity of the force used by the guards shouldn’t be underestimated. Jimmy Mubenga, a man detained inside one of Britain’s male detention centres, suffocated to death while G4S guards attempted to take him aboard one of these very same flights, using force that failed to comply with their training.

These chartered flights are intentionally kept secret; there is no set date or time. For one young couple, this meant not saying goodbye to her partner as she was ‘returned’ to India. But, for international governments, the hidden disappearances are what gives these places power. Their secretive nature gives the British government a veneer — one that allows William Hague launch a very public campaign, with Angelina Jolie, about how rape is used as a weapon of war and the need to prevent it. Many women inside Yarl’s Wood have fled this very same thing, but it is our part of our policy to detain them, causing more harm. The home office have refused to reveal whether women have been raped at Yarl’s Wood, with a staff member telling the Independent that “disclosure would, or would be likely to, prejudice the commercial interests” of the people running the centre. Similarly, the hidden nature of these centres allows the United Kingdom to say that it proudly defends the LGBT community while simultaneously deporting individuals who could face persecution for their sexuality. Due to the ways in which invisibility is forced on these asylum seekers, there can be almost no resistance. What it actually means, is that the resistance must be visual.

Aside from the horrific stories of the women’s treatment inside, one of the reasons Yarl’s Wood has received so much attention is due to the continued efforts of Movement For Justice. Since 2015, the organisation has planned actions, now reaching several thousand attendees, outside the detention centre’s walls. The sheer mass of bodies, signs and colourful smoke passes over the facilities’ fences, acknowledging and reminding us of the continued presence and struggle of the women inside.

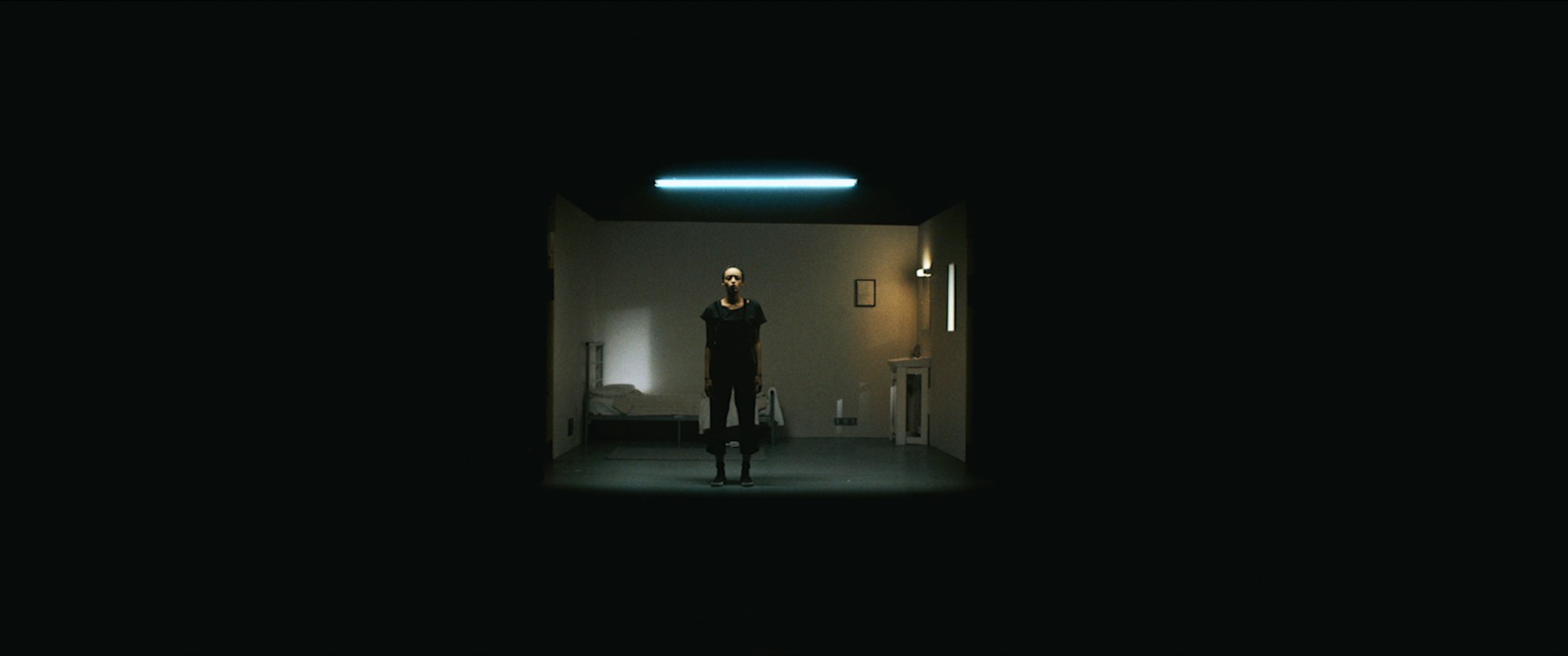

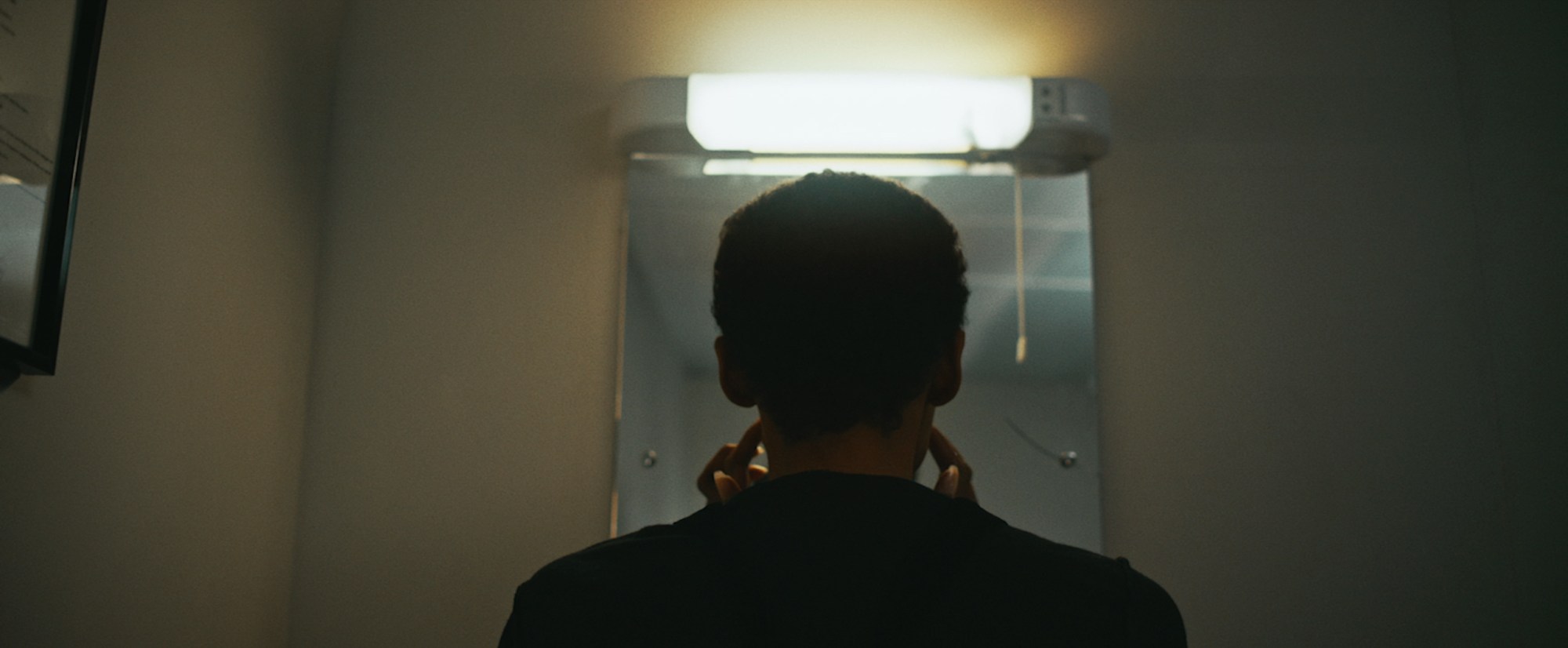

With my documentary, Calling Home, I took motivation from Movement For Justice and shone visibility on the lives of the women inside Yarl’s Wood. It is no accident that the women aren’t allowed camera phones and that the position of all these detention centres is as far away from towns and transport as possible (you have to take a two hour long train and a taxi before you even get to the detention centres gates). Even if we had been granted access for our film, it would have been mediated through SERCO and the Home Office. So we had to think creatively instead, and the constraints on our style turned out to be a blessing. Rather than taking a rigid approach to documentary, we borrowed techniques from fashion and art, and collaborated with performance artist and founder of She-Zine, Diana Chire, to amplify the voices of the women inside. And, as the women told me, they were excited to contribute to a piece that would present their experiences in a new light.

As the women inside don’t have the ability to represent themselves, as a filmmaker, I felt a greater responsibility to take a more collaborative approach to my questioning, and instead of asking them about the various traumas they have suffered and forcing them women to relive it, we decided to chat about Beyonce’s new album, Rihanna’s hairstyles, and how they missed certain brands of make-up from the outside. Of course, the pain of being held in detention emerged, but in a way that many people can understand and associate with. Dorcas, one of the women interviewed, told me, “I was so desperate to have a sense of me again, I used staplers from the post-room to pierce my ears”.

In a time when society is growing increasingly divided, we need to fuse forms to generate work that, whilst remaining political, speaks to a wide range of people. A powerful example of this was Yasiin Bey’s decision to use his body and fame to undergo the force-feeding practice used against prisoners of Guantanamo Bay. In the video, by Asif Kapadia (Amy; Senna), Bey submitted his status and body to highlight the torture that people routinely undergo there, using his fame to attract an audience who may have never acknowledged or engaged with the suffering of the people held there. Look also to the political but funny music videos of Swet Shop Boys, such as T5, where the rappers put their own personal experiences of racism to a beat. These approaches are more important now than ever before.

It is easy to dismiss people who don’t agree with us as ignorant and stupid, but as it has been widely noted, if we are to take away one thing from the vote for Trump and Brexit, we should recognise that people are fed up and disillusioned by the ‘establishment’: politicians who lie to them and a media that ignores or belittles them. Whilst this is having a catastrophic impact on global politics, it means there is also an opportunity. This sense of dissatisfaction tells us that people are fed up with old-fashioned ways of receiving information or knowledge. Rather than complain about them, as artists or creators, it is our job to look for new ways to engage them.

Calling Home has been produced as part of the Postcards series by Just So.

Credits

Text Jade Jackman