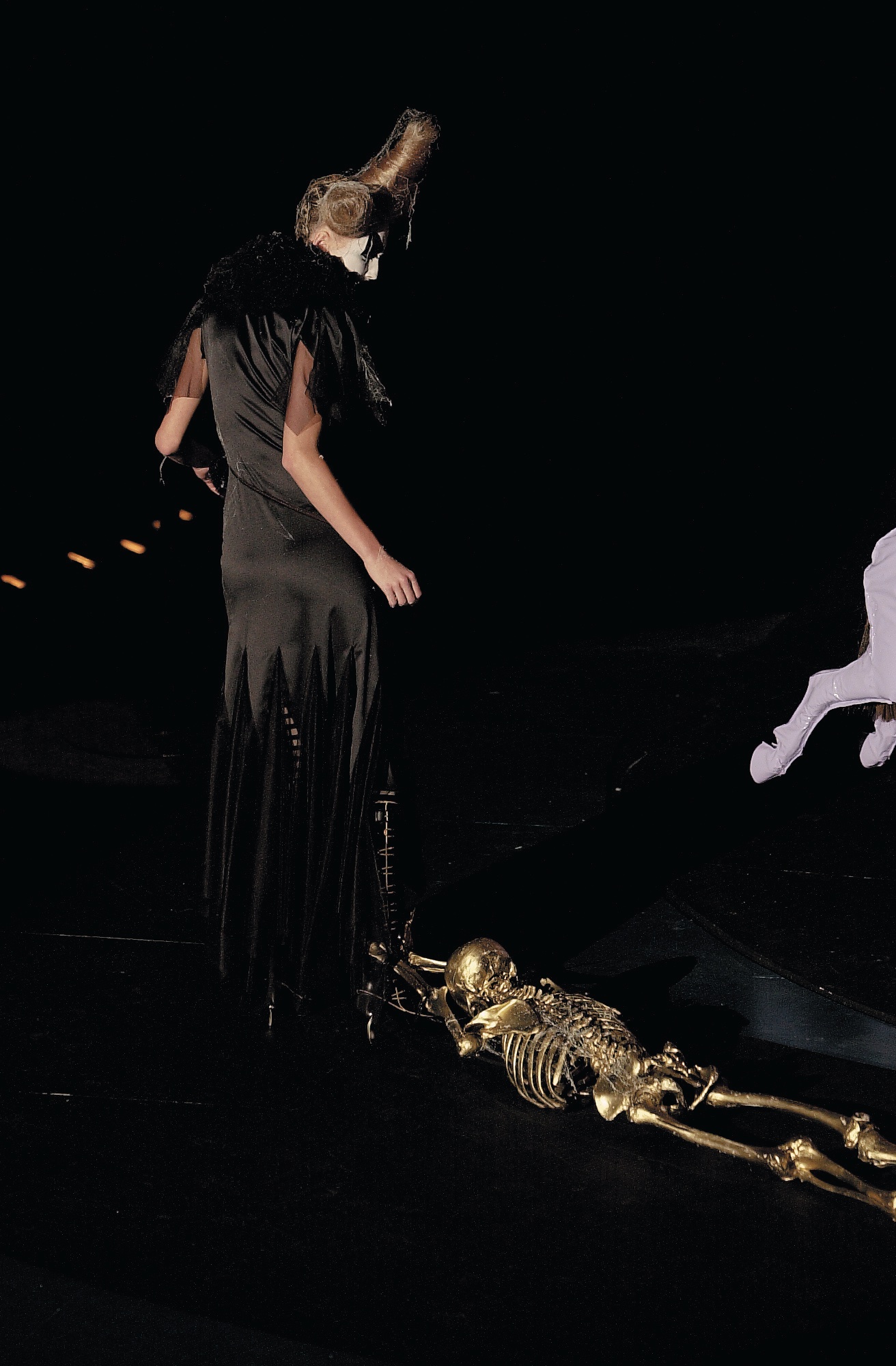

Richard Avedon’s In Memory of the Late Mr and Mrs Comfort was first published in The New Yorker in 1995. Across 24 images, supermodel Nadja Auermann played a beautiful, troubled wife dressed by the world’s best designers of the time: Jean Paul Gaultier, Maison Margiela, Hussein Chalayan, Alexander McQueen, John Galliano, Comme des Garçons. Her husband was a skeleton. Sometimes appearing in rakish hats and tailored overcoats, sometimes naked to the bone, eye sockets gaping, together they spun out a macabre fable of family life – sex, cleaning, china doll babies, and all.

Fashion and death have often been strange bedfellows. In 1824, the poet and philosopher Giacomo Leopardi published his curious “Dialogue Between Fashion and Death”, featuring fashion telling death that “we both equally profit by the incessant change and destruction of things.” In The Arcades Project, which the theorist Walter Benjamin worked on between 1927 and 1940, he commented that “fashion consists only in extremes… Its uttermost extremes: frivolity and death.” We have always been intrigued and troubled by fashion’s rapid pace, exploitative underbelly and intimate connections with the human body, and fashion, in turn, has often dabbled in the morbid and macabre.

The late 1990s and early 2000s were a particularly death-obsessed time, thanks, in part, to many of the designers whose work featured in that spooky Avedon spread. In 2003, academic Caroline Evans published Fashion at the Edge: Spectacle, Modernity, and Deathliness – a book that has acquired something of a cult status among fashion students and style nuts for its elegant and revelatory look at various designers who came to prominence as the 20th Century hurtled towards the 21st.

From Alexander McQueen’s vertebrae corsets and shows featuring asylums and hellfire, to Hussein Chalayan’s decomposed fabrics and Galliano’s raiding of the historical dressing up box, Evans took the temperature of then “contemporary fashion, with its inflections of money, sex and mortality,” and found it a place of high anxiety, big spectacle, sickly imagery, and a taste for shock. It was a time when Jigsaw released adverts of men falling from buildings and Diesel trafficked in car crash glamour, when designers like Andrew Groves could release a collection titled ‘Cocaine Nights’ – sending a model shimmering in razor blades down a white powdered runway – and get a relatively favourable write-up on the BBC. “[At] the edge of centuries, and on the edge of technological transformation,” the mood was darkly provocative. The future beckoned, but it also frightened. On the precipice of change, the fashion industry responded with clothes and images that aimed to disturb.

Twenty years after publication, Fashion at the Edge is being reissued by Yale University Press. It is still a wonderful read, answering questions that remain just as relevant today (why does fashion recycle the past obsessively and cyclically?) while also capturing an era of design we constantly pick over, even as it grows ever more distant from our own. “It’s a very partial account,” Evans explains over Zoom, acknowledging how it sidesteps other prominent movements, such as minimalism. “But this particular strand really struck me as part of that late 90s aesthetic… I’m just an old goth, you know. And it’s surprising that slightly goth sensibility popped up in quite mainstream fashion.”

Over the last two decades, mainstream fashion has stopped being as preoccupied with death. In fact, it’s moved so far away from the kind of explicit explorations found in the nineties and noughties that much of the imagery from that period would likely stir outrage were it being produced now – models as corpses, implications of insanity and ill-health. The goths have sloped off back to Camden, and the skeletons have been banished from the closets.

SUBSCRIBE TO I-D NEWSFLASH. A WEEKLY NEWSLETTER DELIVERED TO YOUR INBOX ON FRIDAYS.

The reasons for this are complex, but various roots are found in Fashion at the Edge. What Evans identified was a world in flux, fashion acting as both a mirror of and sensitised reaction to new technological possibilities (which meant new means of communication and forms of media), as well as all the fears and pleasures of modern living. Many of those frontiers now feel quaint: Hotmail, dial up, chunky mobile phones. Google was founded in 1998, Facebook in 2004, YouTube in 2005, Twitter in 2006. Now we have constant access to the rest of the world. News is filmed, photographed and updated in real time, with rolling headlines and minute by minute coverage. These changes have brought us closer to death – wars, mass shootings and true crime style dissection of murders interspersed with red carpet coverage – and in doing so, made it both less shocking and perhaps less appropriate to riff on creatively.

Those same tools that transformed the way we absorb information have also served to catapult fashion from something relatively niche or at least industry-focused to a form of mass entertainment. When Alexander McQueen was the first designer to livestream a show in 2009, it was a statement – the curtains pulled back to invite in a wider audience. What began as an upending of hierarchies has since exploded into a totally new way of viewing fashion. “It doesn’t just exist as an object anymore,” Evans observes. “The primary fashion object was the dress or whatever, and the journalism, the photographs, were secondary.” Now the image rules all. What this means, crudely, is that shows, editorials and events are presented as things that everyone can form an opinion on. From Schiaparelli’s faux-animal heads and Balenciaga’s blunders to questions of whether a Met Gala guest was sufficiently on-theme, there is an avid mainstream interest in the fashion industry’s output – and a desire to react to it instantly.

Although one could argue that such democratisation is largely a good thing (it’s certainly lucrative), it also leaves less room for designers to work allegorically or riskily without fear of a backlash that isn’t just critical but global and immediate. To keep with McQueen, the kind of macabre territory he explored – his AW95 Highland Rape collection, for example, exploring the consequences of the Scottish clearances – is all but impossible to imagine emerging today without serious upset.

Of course, the fashion industry should not be immune to criticism. One useful development over the last twenty years has been a shift from thinking about death symbolically to thinking about it practically. The fashion industry is phenomenally destructive, both in its environmental impact and the toll of its human exploitation. From the collapse of the Rana Plaza building to cotton produced through Uyghur slave labour, the clothes we wear are often tainted by suffering and death. Marx wrote about the “murderous, meaningless caprices of fashion” in 1887, and very little has changed since – other than the outsourcing of exploitation to other countries where labour is even cheaper. A renewed emphasis on the realities of clothes production may not be as sexy a topic, but it is much more vital.

Within the realm of narrative and symbol, some allusions to death do continue – though they have taken new forms. Dilara Fındıkoğlu may be keeping the dark spirit of McQueen alive, but today’s designers often approach death more abstractly through invocations of wastelands and apocalypse. From Balenciaga’s floods, fire and mud runways to Marine Serre’s unsettling visions of environmental destruction, contemporary anxieties continue to seep into mainstream design. As Evans wrote more recently in an essay ‘End Times, Future Visions’ for E/MOTION: Fashion in Transition, “fashion, at moments of crisis, has imagined its own future, be it utopian or dystopian.” Many brands are currently retreating into the safe territory of escapism or consumer-friendly branding, but a handful are still willing to trouble their audience with more dystopic ideas about global instability and the climate crisis.

As Evans observes in the same essay, fashion can still be a powerful tool with which to confront audiences. She uses the example of Pyer Moss’s Kerby Jean-Raymond, who in 2015 staged a show focused on police brutality that featured interviews with the relatives of Black men killed by the police including Eric Garner, Sean Bell and Marlon Brown. At such moments, fashion can be used to explore death not as something abstracted, not as an idea, but as something tangible and painful, rooted in current social and political injustices.

To write about why fashion is or isn’t interested in any one thing at any given time is to attempt to sketch a coherent portrait of what the industry was, what it is becoming, and how it exists within the wider sweep of history. Other reasons could be given for the diminishing interest in deathly aesthetics: corporate brands giving creative directors less time to research and let ideas percolate, allied with that fear of anything too controversial; the fashion industry’s shift to expressing its contradictions and price tags through irony instead of destruction and decay (Virgil Abloh’s quotation marks, Balenciaga’s £1,290 calfskin trash bags); an understanding of – if not always a willingness to act on – the need to move away from the kind of uber-thin models whose bodies were used to accentuate these morbid ideas; on and on it goes. “Our common nature and custom is to incessantly renew the world,” Fashion tells Death in Leopardi’s dialogue. Fashion’s life cycles are fascinating – capricious, ravenous, relentless. For now death may have been consigned to the shadows, but, like a ghost, it’s never really gone.

Credits

All images taken from Fashion At The Edge by Caroline Evans, courtesy of Yale University Press.