The state of the “millennial” is a complex and nebulous thing. Some define Generation X by its widespread affinity for decorative succulents. Some note an eye for a very specific, and hotly debated, shade of apricot-salmon pink. Others scorn millennials for the remorseless, cold-blooded murder of wine corks, the napkin industry, and — may she rest in peace — fabric softener. But perhaps one of the defining experiences that unifies the Y2K generation is the birth, sophistication, and pervasive influence of the internet, which has dramatically altered and continues to shift the way we communicate — through social media, through the language of texting, or otherwise — and how we process information.

A just-opened exhibition at the Museum of Contemporary Art in Chicago seeks to put into language the idea of the “millennial,” focusing on how the advent of the internet has changed the way we experience the world. Aptly named I Was Raised on the Internet, the landmark show features nearly 100 interactive artworks from 1998 to the present, spanning photography, painting, sculpture, film, and video, as well as emerging technologies, like Oculus Rift and interactive computer works, and platforms like Facebook and Snapchat. Various pieces from a global curation of artists examine the impact of gaming, entertainment, smartphones, and social media, pointing to the emergence of original vocabularies within the new millennium, as well as developing ways of processing culture as the result of constant online exchange.

Throughout the exhibition, viewers are invited to become active participants, interacting with works both in the galleries and via a microsite created specifically for this show, which hosts a number of web-based artworks accessible from anywhere with an internet connection. Divided into five sections that each describe a different mode of interaction between art object and viewer, works explore fluid forms of identity and digital performances of the self in Look at Me; Touch Me examines the extent to which digital information can be translated into physical space; surveillance and data collection is addressed in Control Me; Play with Me documents the advancement toward fully immersive technologies; and Sell Me Out critiques corporate culture and consumerism.

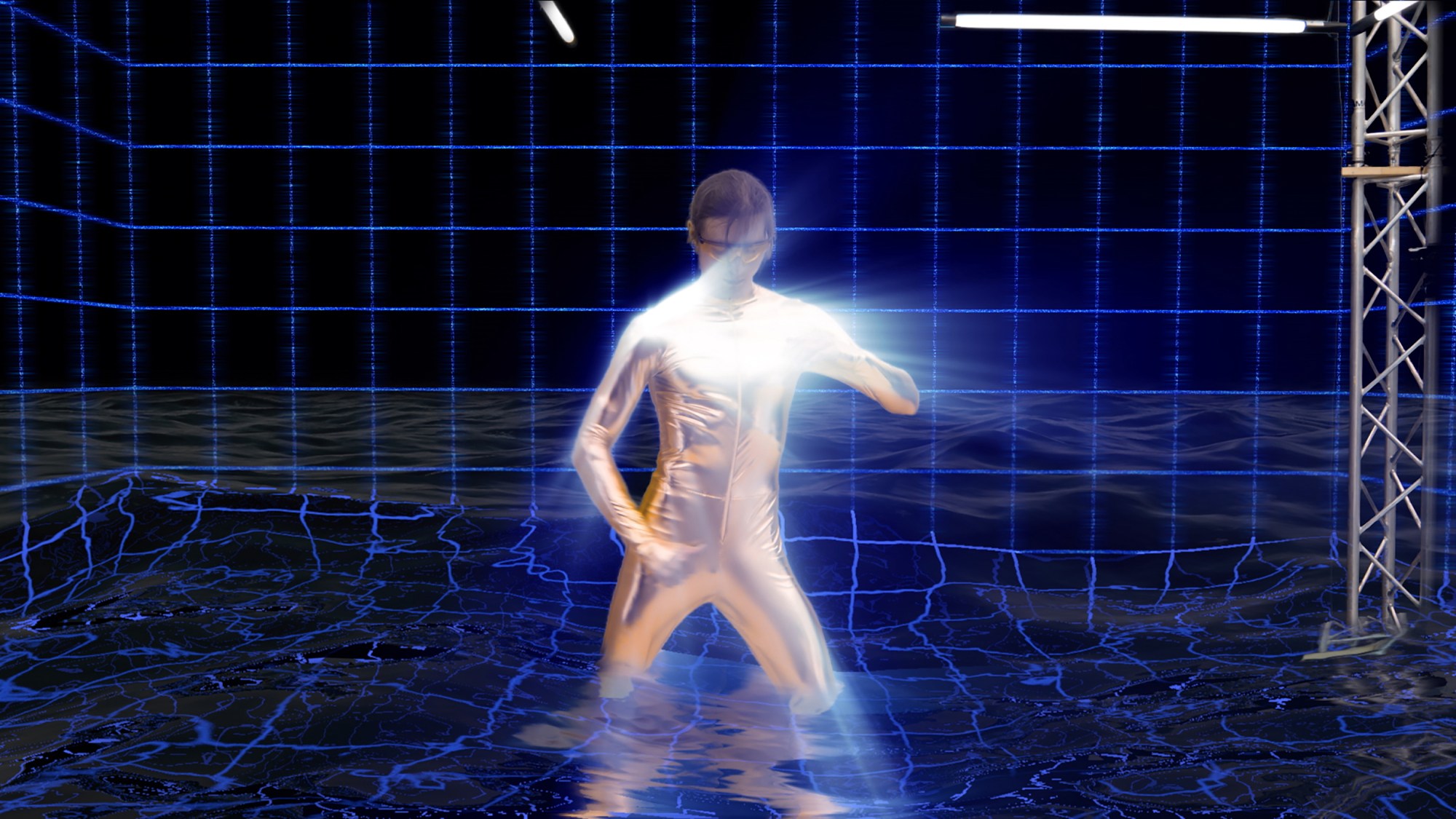

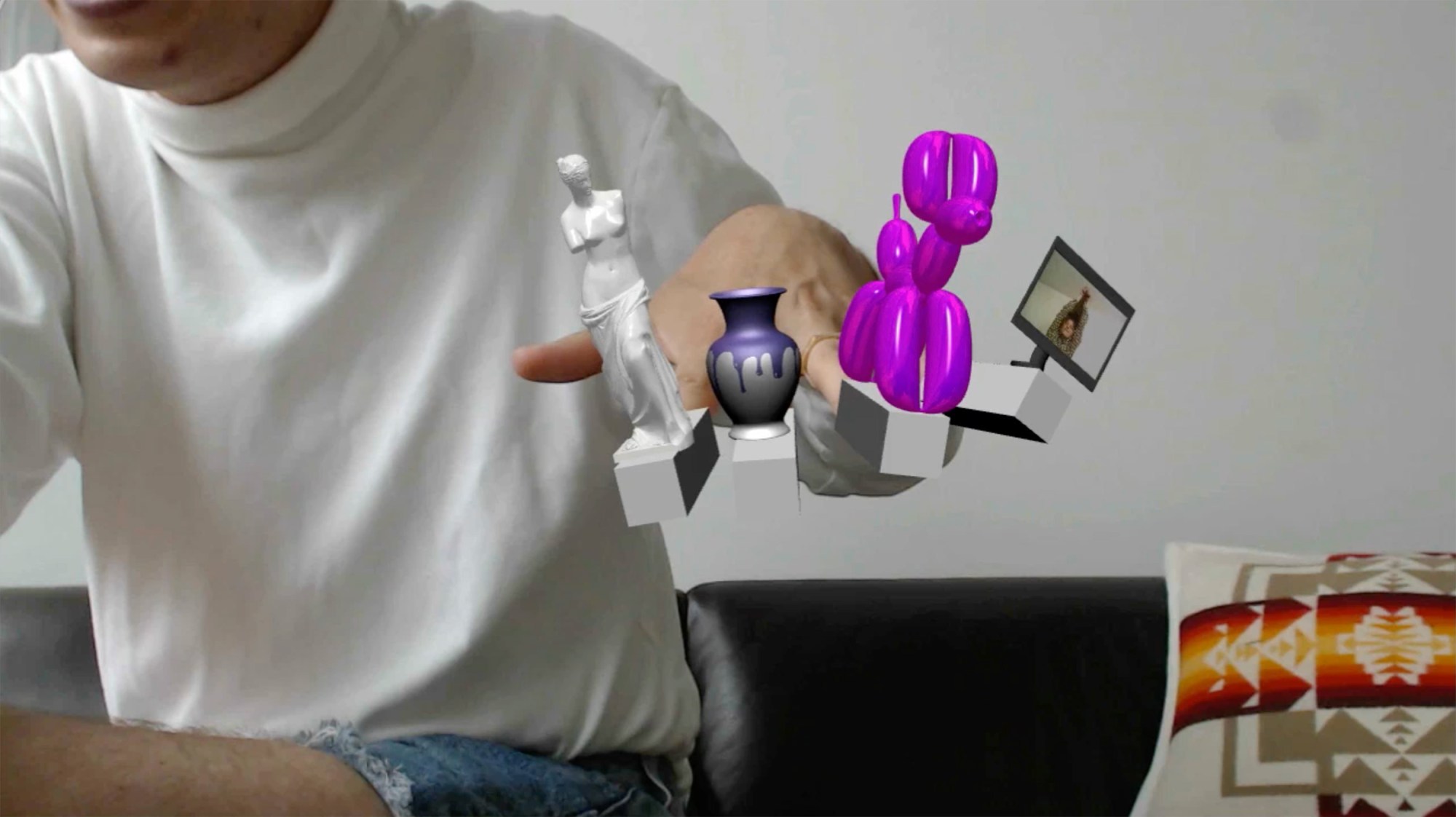

In Look At Me, Amalia Ulman discusses selfie culture and the performativity of social media through her five-months long performance Excellences & Perfections, in which she created a new, scripted identity documented through photos and captions on Instagram and Facebook. She caricatures a consumerist lifestyle and undergoes an extreme, semi-fictional makeover, pretending to have a breast augmentation, strictly following the Zao Dha diet and attending pole-dancing classes, and posting photos in expensive lingerie amid curated interiors rife with floral bouquets. Digital artist Jon Rafman, typically known for his work with Google Street View, presents “Transdimensional Serpent” in Touch Me, in which viewers sit atop a giant, white snake and are then transported via Oculus Rift into a virtual reality experience at once beautiful and disturbing. In Sell Me Out, viewers encounter Hito Steyerl’s immersive video installation Factory of the Sun, which plays within a dark room overlaid with a grid of fluorescent light, immediately reminiscent of Tron’s sci-fi cyberspace. The video, which debuted at the German Pavilion at the 2015 Venice Biennale, follows an absurd narrative — a critique of surveillance culture told through a blend of news coverage, video games, and dance videos — about workers forced to create sunlight by moving within a motion-caption studio but are given the chance to fight back against the powers that be.

“I think [the internet] has made people more comfortable with digital forms of expression, recognizing that highly sophisticated visual material is being put in front of them every day as they surf the internet,” explains Chief Curator Michael Darling, when asked how the internet has changed the way people interact with art. “It has also opened people up to the beauty of unforeseen discoveries, the strange juxtapositions that happen when searching the internet, and the poetry and beauty that can come out of those unscripted detours.” Darling points to the internet and online search engines as vehicles for the democratization of access to art, giving the wider public the ability to view works from around the globe and across the spectrum of creativity. “Digital video, digital photography, and 3D-printed sculpture are all very familiar to a broad populace now. To see these forms in the museum is no longer an oddity.”

“This show is important to show that digital art has reached a point of maturity where it is as visually sophisticated and stimulating as other art forms while also dealing with the most pressing issues of our time,” continues Darling, who notes that he sought a wide and complex variety of expression when curating the show, as well as artworks that can allow us to raise questions about the different aspects of life on the internet. “We finally have a critical mass of artists and artworks that proclaim we are in the post-internet era which act like a signpost for us at this point in human history.”

“I Was Raised on the Internet” will be on view at Chicago’s Museum of Contemporary Art through October 14.