Prom is spiking the punch bowl. It’s Purple Rain, plastic crowns and gymnasiums. For thousands of teens across the States, prom is a big cinematic ideal of a night (hopefully more John Hughes than Carrie) anticipated long before senior, or sometimes junior, year. Few events are supposed to represent being a kid in America — or rather struggling to become an adult in America — as much as prom. Roughly 5% of teens will lose their virginity on prom night; the average household will spend nearly $1000 on dresses, tuxes, hair and limos; and the hashtag “prom” offers up 9.5 million different versions of the prom experience.

Last year, an article on Slate suggested that “2014 may be the year in which we, as a society, have reached peak prom.” It was the year in which “promposals” and the meme #prahm (“prom” said in the style of “ermahgerd”) went viral. But, in truth, 2015 may be the year in which prom has reached peak social significance — especially as it concerns queer students.

In May, 18-year-old Angie Esteban made headlines when she became the first trans prom queen at Salinas High in California. And in April, Maka Brown, also 18, became the first trans prom queen in Utah — a state with one of the most historically trans- and homophobic school systems in the country. Prom is changing, or rather the world is changing and prom is on the frontline — a small and unique platform on which the zeitgeist manifests itself in miniature. And while that visibility also shows up our societal shortcomings (see: the prom-bound students who recently posed with assault rifles and a Confederate flag), on the whole it shows a trend for increasing acceptance. Today’s generation “is more accepting of people who are different,” said Brown. One of her schoolmates agreed, adding, “Maka has broken a lot of boundaries in our school. We’re all proud of her.”

Perhaps equally surprising in Utah: Maka’s king on the prom court at Salt Lake City’s School of the Performing Arts, was Jasper Clayton, who is openly gay. About their crowning he said, “It made huge waves in the media. And everyone at our school was like, confused why it was in the news. No one had a second thought. It’s just normal.” But it wasn’t always that way.

In 1996, Utah became the first state in the U.S. to outlaw gay clubs in schools. After 16-year-old Erin Wiser (now a transgender man) and his then-girlfriend Kelli Peterson attempted to form a club for LGBT students at his school in Salt Lake City, the Utah Senate signed a law “that required schools to risk losing federal funding and ban ‘specified school clubs’—code for anything gay-related.” The ensuing legal battle became one of the most publicized cases in the fights for LGBT rights in US history. And as an article on the Daily Beast points out, it broadened the focus of that struggle from AIDS and Act Up to encompass LGBT youth. On a personal level, Wiser was subjected to intense homophobia at school: “The other kids at school were shits. They threw things at us, bullied us. It’s hard to describe,” Wiser told the New York Times. Some of the students filed a petition to start an “Anti-Homosexual League.” However you look at it, a lot has changed since 1996.

Though, legally, schools in the States have been required to allow same-sex couples to attend prom since 1980, LGBT students have often done so at their own risk. Take the landmark lawsuit Fricke vs. Lynch that resulted in the 1980 legislation. In 1979, Principal Richard Lynch of Cumberland High School in Rhode Island denied gay student Paul Guilbert’s request to bring a male date to prom, “fearing that student reaction could lead to a disruption at the dance and possibly to physical harm to Guilbert.” The next year, Guilbert’s friend Aaron Fricke was also told he couldn’t bring a male date to prom and took Lynch to court. The hearing ruled that “even a legitimate interest in school discipline does not outweigh a student’s right to peacefully express his views in an appropriate time, place, and manner.” Fricke and his date tuxedoed up and hit prom but the school still felt it necessary to hire six policemen for protection and Fricke and his date were heckled on the dancefloor.

According to California trans prom queen Angie Esteban though, “it has gotten better.” Esteban had previously nearly dropped out of middle school: “I used to fight a lot and get suspended from school. I would get bullied but I would bully back,” she told her local paper after her coronation. But in her senior year, she says, things have improved. “This year they turned out to be more open minded” she said of her classmates. And one of her teachers noted that “since the prom nobody’s given her any trouble.”

While it’s impossible to say that things are improving everywhere for trans and gay kids based on the experiences of prom queens Maka Brown and Angie Esteban (there are of course many, many more instances of the continued, devastating hardships that LGBT kids endure — remembering in particular the death of transgender activist and prom king Blake Brockington earlier this year), these two examples do prove a few, encouraging, things. One, that we are at least making progress, however slow. Two, that the role of young people (including Wiser and Peterson and Fricke) in driving that progress forward is unquantifiably important. And three, that prom — as the liminal, zeitgeist-capturing moment that it is — is a battleground where the fight for acceptance can and is being fought.

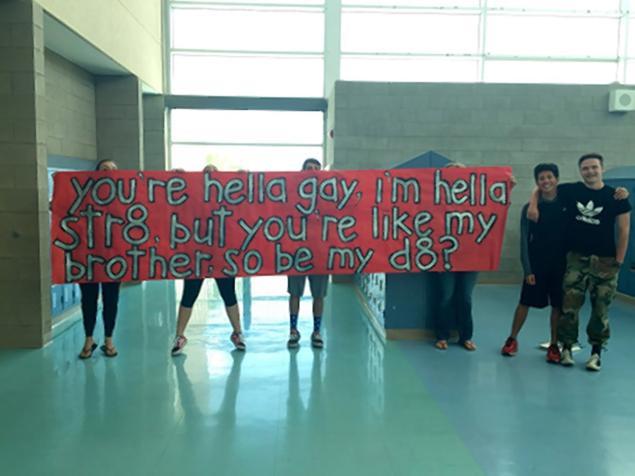

And of course that battle is happening outside of schools, too. One benefit of the, let’s be real, often mega corny local media coverage of promposals has been increasing visibility for non-heteronormative couples and non-traditional prom pairings. Ellen DeGeneres was so moved by the viral sensation that was the promposal of straight highschooler Jacob Lescenski to his gay best friend Anthony Martinez that she invited them onto the show and wrote them each a human-sized check for $10,000.

Taking a bigger step back: Was 2014 the “trans tipping point” that Time magazine heralded with its May issue, fronted by trailblazing trans actress Laverne Cox? We truly, truly hope so. “We are in a place now,” Cox told Time, “where more and more trans people want to come forward and say, ‘This is who I am.'” And if we needed more proof, it came, this week, in the proud, corseted form of Caitlyn Jenner.

Despite its posse of accompanying teen-movie cliches, prom is its own kind of tipping point. It is the time at which 18-year-olds literally promenade themselves, and who they want to be, as they prepare to enter the real world. In the words of the late photographer Mary Ellen Mark, who spent four years attending and documenting proms with her husband, filmmaker Martin Bell, “I think the prom is very serious. It’s an American ritual, it’s a rite of passage, and it’s very much a part of this country.” If the notoriously bitchy teen overlords of the prom committee can open their arms to a more diverse student body, isn’t it about time the rest of the country followed suit?

Credits

Text Alice Newell-Hanson

Still from Mean Girls