When Syd Shelton returned to London in 1977 after fours years living in Australia, he was shocked at how much things had changed. “The recession had really hit and the Callaghan government had attacked living standards for working people – very similar to what’s happening right now,” he explains. “Whenever that happens, there’s always a rise of something like the National Front.” Syd was desperate to fight against the hatred and was lucky to meet one of campaign group Rock Against Racism’s founders, Red Saunders. Before long he was their unofficial photographer and designer for their newspaper/zine Temporary Hoarding. With an exhibition of his work from that period opening up at Rivington Place next month, we caught up with Syd to hear about some of Britain’s most tribal and transformative times.

So what were the main messages of RAR?

Putting black and white bands on stage together was a political statement in itself. We didn’t go on stage shouting “smash the National Front” and all that sloganeering, but we did want to extend the argument and talk about Zimbabwe, South Africa and apartheid, Northern Ireland, sexism and homophobia. We wanted to go, “Look, the National Front is not just against black people, they’re against all of this as well.”

Why does the exhibition just cover 1977-1981?

Like Jerry Dammers said, two tone took over the baton, so in a way we’d succeeded because bands were multi-racial. And the chemistry was starting to fall apart a little bit. We were all exhausted. We’d been doing this for five years. Of course, the fight against racism never goes away, as you can see with the anti-refugee situation at the moment. We’re not born racist – we learn it and it takes a lot of looking at the Daily Mail to get that in your head. You have to argue against it.

People can get weary of musicians being political, but this movement shows musicians can make a difference.

We were very lucky, because the chemistry of punk and reggae came together. There was that punk and reggae DIY ethos that was phenomenally empowering, and we all thought we could change the world. I don’t know if people feel that empowered any more.

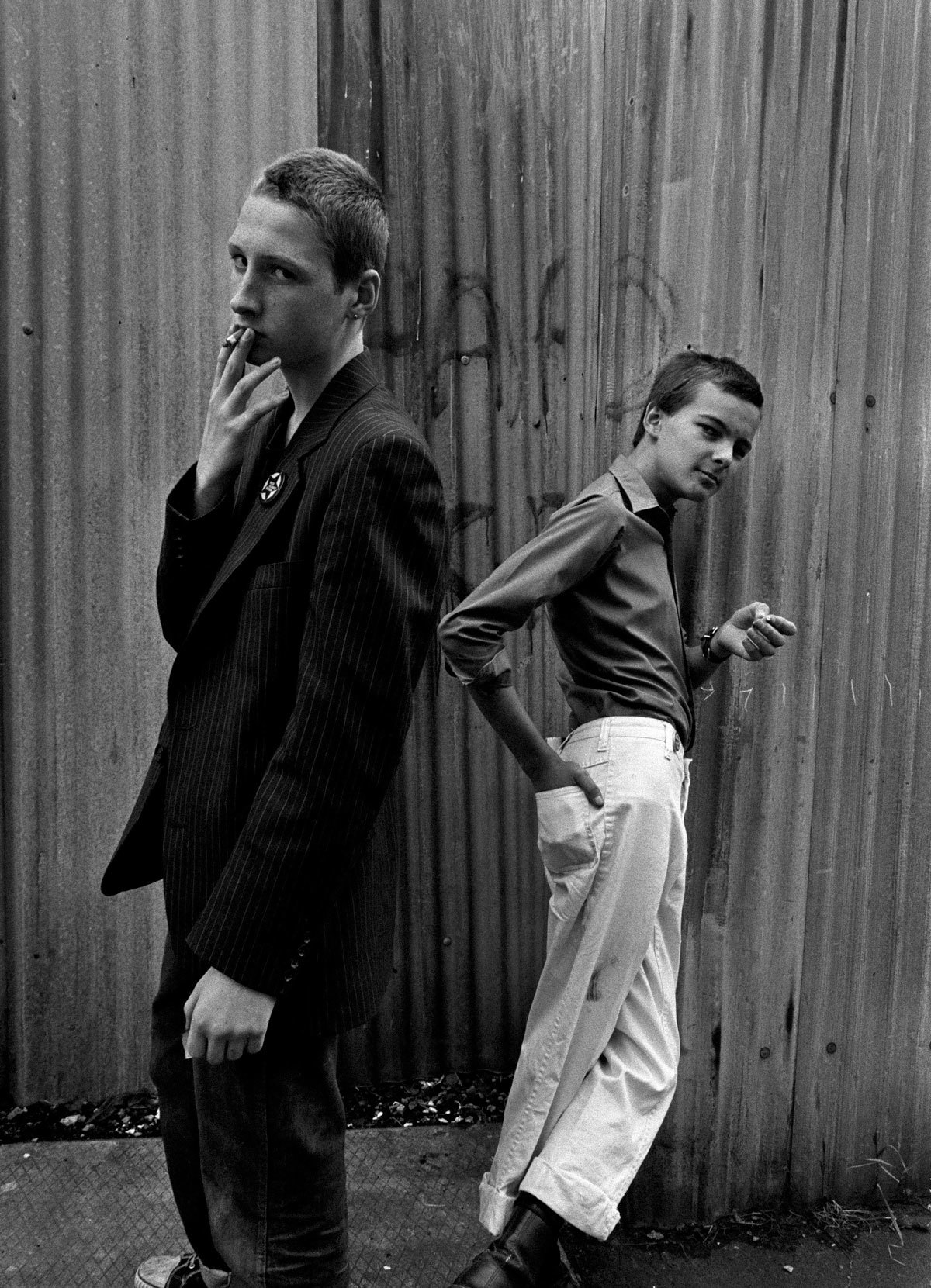

Tell us about the below picture of the two skinheads.

A group of anti-racist skinheads wore RAR badges and it was quite a brave stand because Hoxton in those days was very right wing. There was a man on Old Street roundabout who had painted the whole of his block of council flats with the Union Jack and used to shout at any black people walking past. He was a complete madman. We used to go and taunt him. Young kids like this were quite brave. It was much more difficult to be anti-racist in those days than it is now. As you can see in one of the pictures, the police are protecting someone giving a Nazi salute. The idea of that now is just crazy.

Do you think relations with the police were worse back then?

I’m not saying it’s all gone now, but they were outrageously racist back then. Can you really imagine someone being able to sieg heil and being protected by the police? The police were laughing at me and I was going, “You fascist bastard” and the police were just grinning and laughing.

Can you tell us about your biggest demonstrations?

There was a carnival that we did, which was the most phenomenal demonstration we did in Vicky Park. We decided we didn’t want to just do a concert, but a mass demonstration. It took six hours to get from Trafalgar Square to Victoria Park and there were 100,000 people. At four in the morning, people were coming down Charing Cross Road singing Clash songs. I went to the square at 7am and it wasn’t due to leave until 11.30am and there were already 10,000 people there. There were trains, coaches, people coming in from all over the country. There was an old lady who I used to buy cigarettes from on Bethnal Green Road, Mrs Greer, an old Jewish woman. She’d fought when she was very young against Moseley and the Black Shirts in the 1930s and she said she stood outside her shop and applauded for six hours. She said it was the best day of her life: “All these amazing young people with their amazing haircuts and their clothes. Where have they come from?”

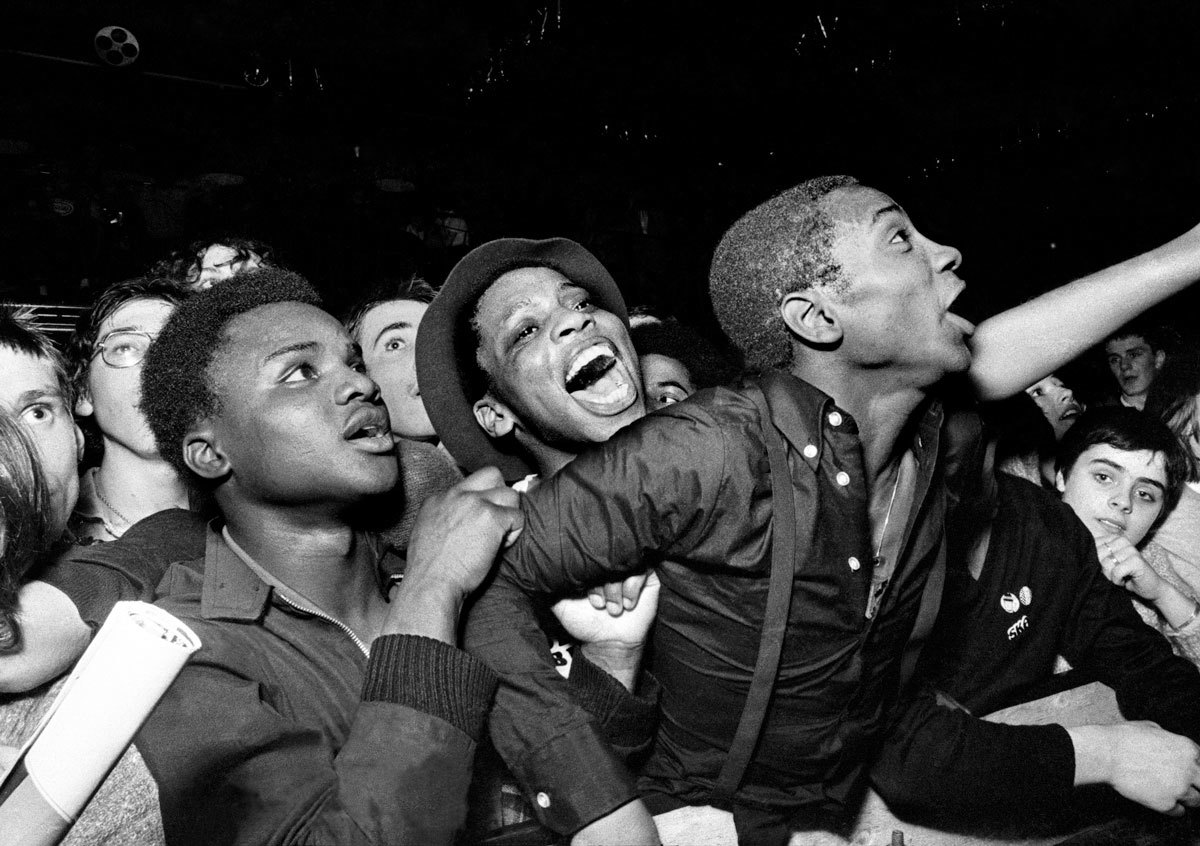

What about the above picture at the Victoria Park concert?

This has been my most successful photo ever. The other thing that was fantastic was the energy factor. There’s a film called Rude Boy that The Clash made that has footage of this and it’s playing White Riot and the whole 100,000 people are pogoing. It’s just extraordinary to see the energy. And this is after they’ve marched for seven miles and danced the whole way as well.

How would people distinguish between the racist and the anti-racist skinheads?

Anti-racists would tend to wear RAR badges. Skins Against The Nazis was another badge they used to wear. There’s a picture of a woman called Sharon Spike who used to be a racist, then went to a RAR gig and changed her mind and became a real activist. She saw how positive it was with black and white bands playing together and thought, “Shit this is great.”

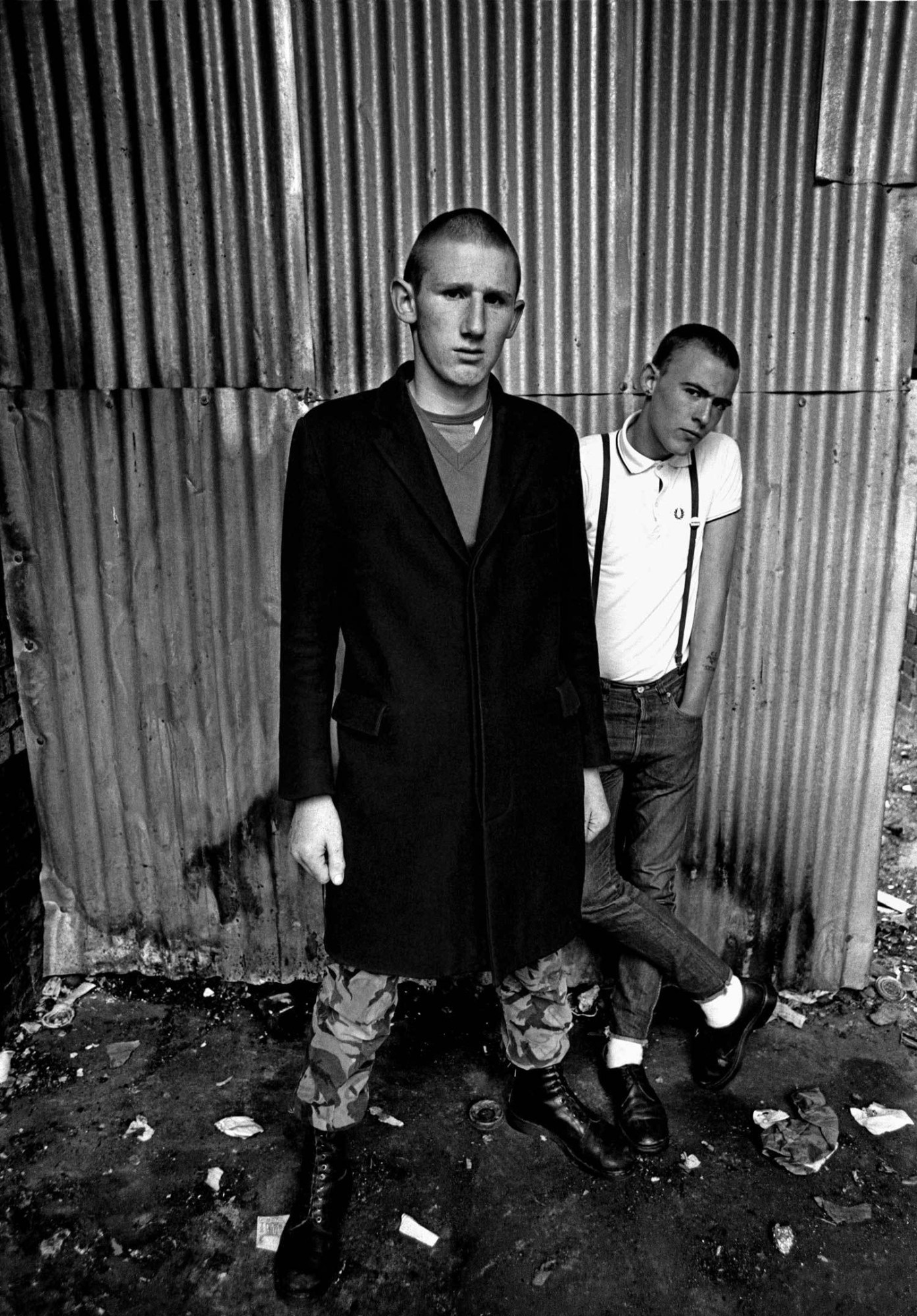

It’s good for people to realise that they can change. Why did you decide to include photos of actual racist skinheads?

Because that was the argument going on and I didn’t just want this to be a heroes’ gallery. I also wanted to show the enemy as well. I like this one photograph [below] I took because I was shaking when I took it. This guy was really heavy and I was talking to them and he was coming out with all kinds of crap and I was saying, “You’re full of shit man.” And you could see his fists clenching. He’s just about to hit me and I said, “Thanks” and I was off!

Credits

Text Stuart Brumfitt

All photography copyright Syd Shelton