The emergence of queer rappers in the past decade has spawned a cultural identity crisis for hip-hop, tempering the genre’s traditionally hyper-masculine tone into something more sexually abstract. The sudden prominence of artists like Cakes da Killa, Mykki Blanco, or queer performance/rap collective House of LaDosha is as intriguing as it is inevitable. The LGBTQ community, previously one of rap’s most ruthlessly targeted groups, has taken both the reins and mic, aesthetically and lyrically expressing themselves within a genre whose opinion on anything outside of the male hetero-norm had been made offensively clear.

In distorting hip-hop’s homophobia, queer rappers have created a niche space where male chauvinism, one of the genre’s undeniable staples, becomes virtually defunct. Queer rap stands in direct opposition to a genre in which Queens rapper Action Bronson, who recently got kicked off of Toronto’s NXNE roster for his song Consensual Rape, pens such lyrics as “Then dig your shorty out cuz I geeked her up on molly,” or “Have her eating dick, no need for seasoning / If seven dudes in the room, then she’s pleasing them.” Another straight rapper, Rick Ross, has no issue thrashing out the whole rape thing in his song U.O.E.N.O: “Put Molly in her champagne, she ain’t even know it / I took her home and I enjoyed that, she ain’t even know it.” Ok, noted: steer clear of straight rappers who offer girls molly.

But in a world where anti-feminist slanders like those of Bronson and Ross are gloomily widespread, the rise of queer rappers and their predominantly male-on-male focus has brought about a few interesting questions: What happens to a genre of music after you eliminate one of its most pervasive themes? How are queer artists discussing sex, as well as sex partners, considering the absence of a two-gender dynamic?

While both straight and queer rappers dabble in sexual objectification, the latter group uses the same terminology to describe themselves as their objects of desire. By boasting with jargon traditionally used to offend, queer rappers help the words lose their lewd, offensive connotations and become harmless—even humorous. For example, Brooklyn-based gay rapper Big Dipper, known for being a heavy-set “bear,” spits “Cause I’m a skank and a lady and I’m down to fuck” in his track Skank. He goes on to say, “You wanna bust a nut to my stiletto strut,” a rare line about lusty, male-to-female cross-dressing. In calling himself a skank, Dipper softens the offensive blow of using similar wording on others.

Rather than their straight counterparts, who brag about six-packs or the size of their manhood, many queer rappers shift the focus of their sexual narcissism to another body part: their rears. Internet darling and critically acclaimed gay rapper Le1f (Khalif Diouf) brags “Papichulo got his hot paws all over my boy-culo” in his track Boom. Cakes Da Killa (Rashard Bradshaw), another one of the scene’s most prevalent gay voices, vaunts, “I’m looking right, pussy tight” in Living Gud, Eating Gud. Slightly less explicit, Zebra Kats (Ojay Morgan), a gay rapper whose single Ima Read was referred to as “queer rap’s crossover hit,” spits about his “dirty city kitty” in Tear That House Up. These guys are familiarizing a male body part that’s rarely mentioned elsewhere in the genre.

In certain cases, queer rappers appropriate female-bashing terms about sex workers to actually empower themselves. In Get Right (Get Wet), Cakes dives in with “Pockets stay on swole, peep the motherfucking cash flow/ Niggas pay my loans just to finger fuck my asshole.” He goes on about twerking like a stripper, noting that he’ll “Charge that nig** double if he think he finna fuck for free.” In hijacking language usually applied to disparage women and instead using it to boast, Cakes eradicates the words of their offensive undertones. Referring to himself as a stripper and borderline prostitute makes these terms seemingly less derogatory or hateful were he to use them on an object of desire.

Many lesbian rappers take a similar approach, often pushing themes of empowerment through female sexuality through their music. Artists like SIYA, Angel Haze, and Brooke Candy are inching their way toward mainstream recognition with swaggering lyrics. For example, in her song Pussy Makes The Rules, Candy boasts, “Ladies don’t be fussy, let the pussy make the rules” and “When you call your hustla play it cool and keep it real / I’ma teach you how to turn ya pussy to a meal.” Perhaps more so than their gay male peers, these girls seem to maintain a similar style to sex as their straight counterparts, like Nicki Minaj or Lil Kim.

However, the purge of misogyny in queer rap has not prevented these artists from exploring the genre’s characteristic vulgarity. In March of last year, Houston rapper Fly Young Red (Franklin Freeman Randall) sent hordes of rap-loving gay boys and perhaps the Interweb at large into a titillated frenzy with Throw That Boy Pussy, a club-ready sexual anthem whose visuals and male-on-male lyrics hold their own against the likes of dirty wordplay mavericks Lil Wayne or Danny Brown. Red redirects the genre’s longstanding sexual objectification from women toward scantily-dressed men, telling boys to “clap that ass like a bitch,” and teasing, “I hit your ass with this dick / Send that ass home limping.” Red’s dominating style aligns more closely with hetero hip-hop artists than his queer peers, possibly empowering gay rappers by blurring the line between the two groups. But this begs the question: is mirroring hetero rap’s attitude toward sexuality something we should admire?

The fact that these rappers are queer inherently deviates their approach to sexuality and gender relations. They’ve invented a world essentially free of male chauvinism—or, at least more free than the straight world. This is due in part to queer rappers reappropriating vernacular traditionally used by hetero artists but within a different context, wherein gender roles have become nearly nonexistent. By using the same words to describe their own sexual competence and that of their sex partners, the lyricism loses its typically degrading and offensive edge. Queer rap has all the raunchy appeal of straight rap, without the abuse.

Credits

Text Mathias Rosenzweig

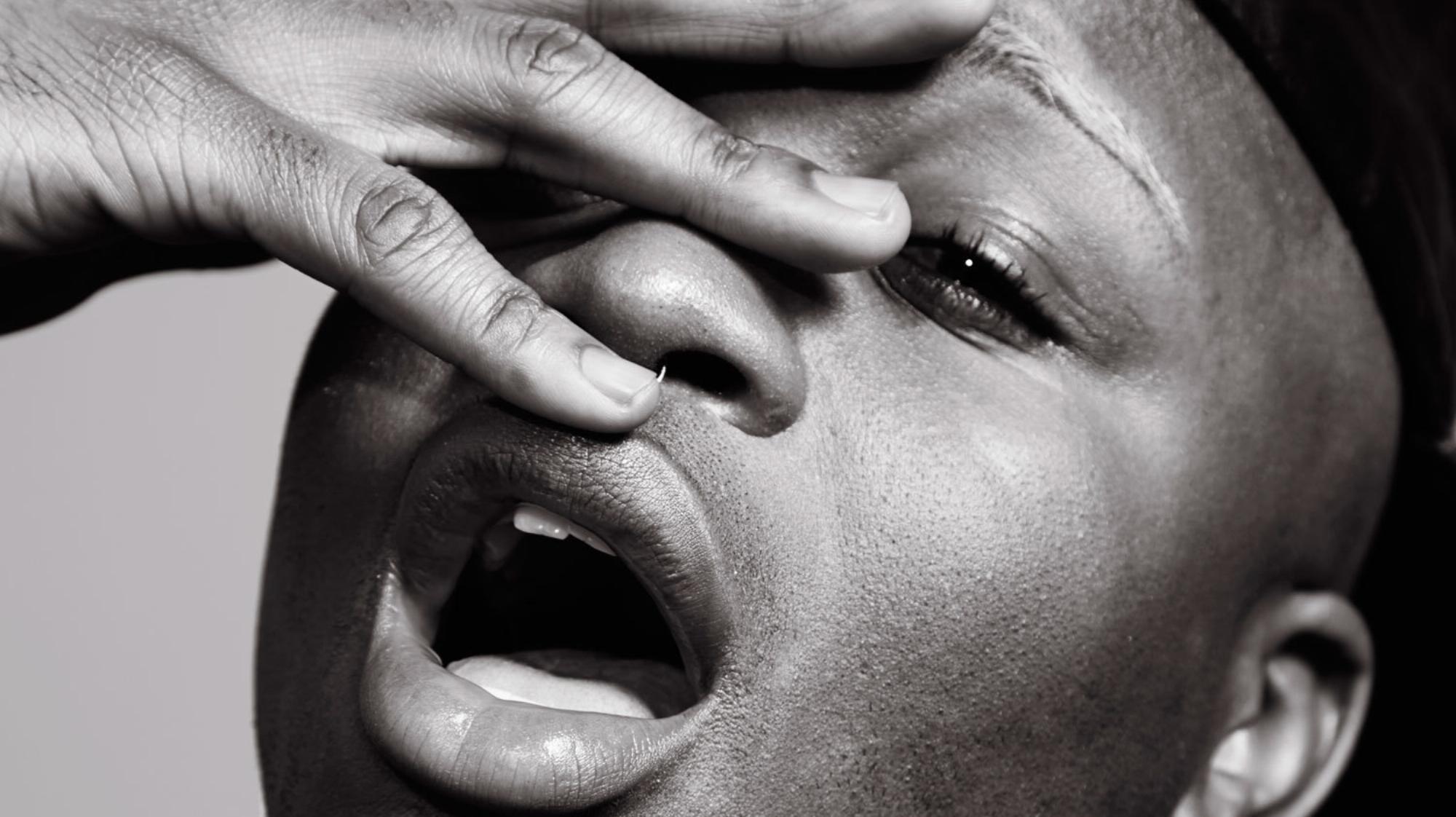

Photography Sam Evans-Butler