Originally from Switzerland, Robert Frank arrived in America in 1947, finding work as a fashion photographer at Harper’s Bazaar. Travelling between Europe, South America and the States, by 1950, he’d shifted to documentary, and in 1955 seven of his images appeared in The Family of Man, Edward Steichen’s ambitious group show that toured internationally for the next eight years. That same year he received the Guggenheim Fellowship. He set off on a series of road trips, producing The Americans, a book of 83 photographs (edited down from more than 27,000) that interrogated traditional aesthetics and how people engaged with photojournalism, provoking audiences at the time but ultimately reshaping the medium.

“Americans were used to photography presenting life in an idealistic way,” says Aimee Pflieger, a specialist from Sotheby’s, where On the Road: Photographs by Robert Frank from the Collection of Arthur S. Penn is currently on display in New York. While Magnum Photos had been established a decade earlier, and Walker Evans (who recommended Robert for the Guggenheim Fellowship) and Dorothea Lange were widely celebrated for their work documenting the Great Depression, Robert’s images were perceived as an assault on convention, conflicting with the polish of Eve Arnold’s Marilyn Monroe photographs and the fashion images of Irving Penn and Richard Avedon, then in vogue. Subsequently, no one in his adopted country would handle the work, and in 1958 Les Américains was released by French publisher Robert Delpire, accompanied by essays from writers such as Simone de Beauvoir.

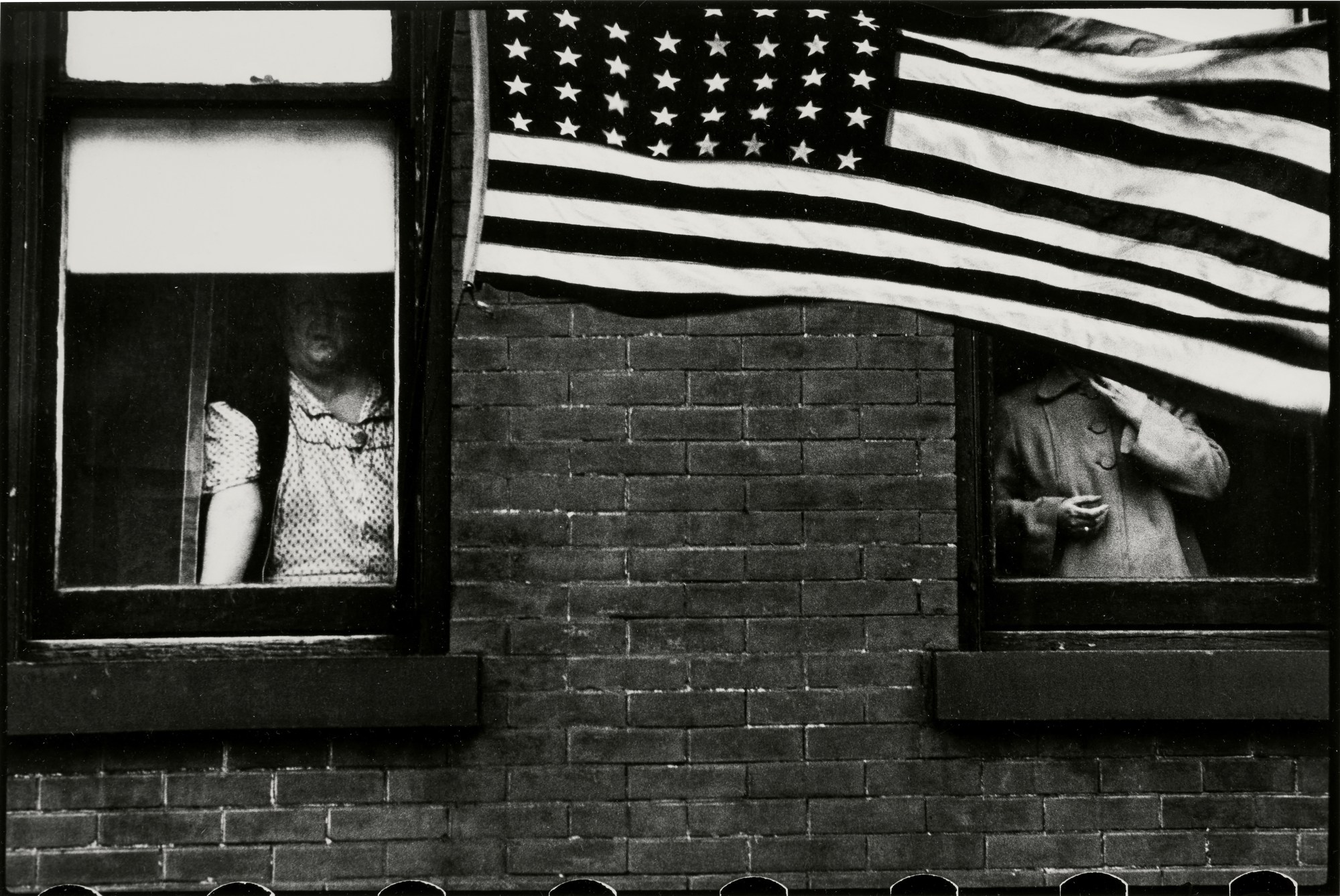

By the following year, an American publisher had been found in Grove Press, and an introduction was prepared by Walker Evans. Too academic for Robert’s liking, Walker’s text was scrapped and replaced with a piece by Jack Kerouac, with whom he’d become acquainted at a party. “The humor, the sadness, the EVERYTHING-ness and American-ness of these pictures!” marvels the novelist in the published text. “Robert Frank, Swiss, obtrusive, nice, with that little camera that he raises and snaps with one hand he sucked a poem right out of America onto film.” Using a simple 35mm Leica, the photographer rejected the era’s common formalities, legitimising a more relaxed snapshot approach. “He was taking the camera off the tripod and really shooting by instinct, literally from the hip,” Aimee says.

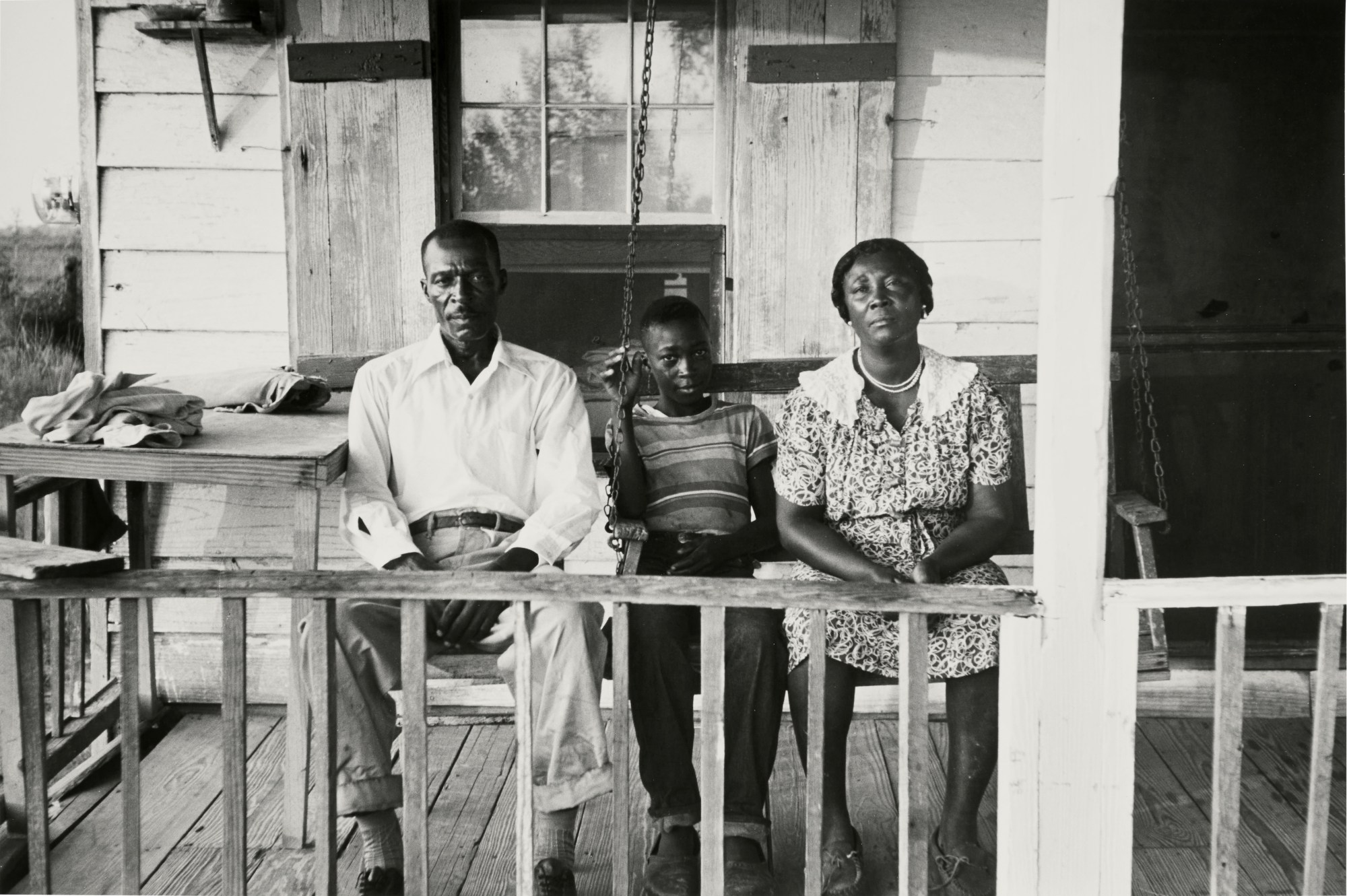

Published two years after On the Road, the author’s endorsement helped encourage people to seek out The Americans. However, reactions were largely critical. Post-war, the country was embracing the American Dream and championing a new affluent wave of consumerism, meaning most people were apathetic about the observations Robert was making — like his cover portrait of segregation on a New Orleans bus — which some considered anti-American. “It’s a book of such simplicity, really. It doesn’t really say anything. It’s apolitical. There’s nothing happening in these photos,” argued the photographer in Vanity Fair in 2008. “People say they’re full of hate. I never saw that. I never felt that. I just went out to the street corners and looked for interesting people. O.K., I looked for the extremes, but that’s because the mediocre, the middle, it’s bland, and that bores me.”

Journals like Popular Photography and US Camera disagreed, criticising him for a style they perceived as sloppy. “They were promoting photography that was not necessarily voyeuristic or experimental in any way, so when Robert Frank comes along and starts presenting photographs of people looking directly into the camera in this confrontational way — these almost drunken compositions where the horizon line is at a tilt, photographs that were super grainy, muddy, and the subject matter as a whole being very confrontational to American culture — people had a problem with it,” Aimee says. “He was reflecting what Americans were giving off to the world, and people didn’t like what they saw.”

The book initially sold poorly. Today it is widely regarded as one of the most influential photobooks of the 20th century. “Within less than 10 years, people were on board, but it took that first publisher to be brave, presenting his work to the world,” Aimee says. The shift mirrored America’s political and social landscape, which underwent a significant period of transformation in the years that followed. “Things were really moving fast. In the early 1950s, we’re dealing with McCarthyism, then later, the civil rights movement was in full swing. By the 60s, you have major political drama going on throughout the world, so people were thrust from this sort of isolated, insular community to thinking about these really heavy political and social concepts. It was not Frank that changed people; people were adjusting to this new world that they were living in.”

New Documents, MoMA’s 1967 show which assembled the work of Lee Friedlander, Diane Arbus and Garry Winogrand, is perhaps the most direct example of Robert’s immediate influence within the art world. Similarly to reactions to Robert’s work, it was considered radical. “I think they were attracted to the immediate, gut instinct of the way he shot,” Aimee says. “That he was humane too; he wanted you to really understand the people that were in his images.” Reflecting on The Americans in 1971, Diane noted, “There’s a kind of question mark at the hollow centre of the sort of storm of [his pictures], a curious existential kind of awe, it hit a whole generation of photographers terribly hard, like they’d never seen that before.”

While momentum for the book only grew, by 1959 Robert had already moved on to directing. His first film, Pull My Daisy, was adapted from Jack Kerouac’s play Beat Generation (and is currently on display at the Barbican as part of an Alice Neel retrospective). However, his most famous film, 1972’s Cocksucker Blues, has barely been seen. Robert followed the Rolling Stones on tour but was later sued by the band due to the incriminating footage he caught. 60 years on, The Americans remains his most significant work, still resonating on a visual and social level. “His devotion to this project was intense and strong, and these images are not only striking for their documentary quality but also very raw and poetic,” Aimee says. “We’re still struggling with a lot of the same problems. His earlier photographs [from 1948] have a sweetness, but once you get to the 1950s he’s been sanded down — he really went through it with The Americans.”

The auction on ‘On the Road: Photographs by Robert Frank from the Collection of Arthur S. Penn’ begins tomorrow.

Credits

All images by Robert Frank, courtesy of Sotheby’s “On the Road: Photographs by Robert Frank from the Collection of Arthur S. Penn”