This article originally appeared in i-D’s The Homegrown Issue, no. 355, Spring 2019.

Streetwear was born out of the hyper-specific locations and hobbies of American bi-coastal youthcultures, practical-but-cool clothes for skaters and surfers in Cali and NYC in the 70s and 80s. It evolved as a DIY reaction to the ideals of the luxury fashion industry and its seasonal schedules, eschewing boring professionalism and prohibitively expensive high quality fabrications in favour of rawness, attitude, creativity, and community. There will always be an argument about what exactly streetwear is, or was, or how it has changed and sold out and lost its soul, but more than anything it was a template, a blank tee ready to be screenprinted. It’s for those same reasons that, in the last 30 years, it’s become a ubiquitous fashion statement for a generation of consumers who are now as likely to be found wandering the endless malls of Seoul and Hong Kong as they are across the endless beaches and skateparks of the USA.

Streetwear may have come of age outside the framework of the luxury fashion industry but soon enough it got co-opted by it. Streetwear – a preserve of outsiders, artists, those weird kids at school – became luxury streetwear, just another fashion style, a worldwide costume for an age of Instagram-flattened taste. A generic silhouette of expensive tracksuits, logo hoodies and baseball caps emanating from the same fashion centres these garments were once reacting against. Just another product in a landfill of products, a profit mark-up in the spreadsheets of another multi-national fashion conglomerate.

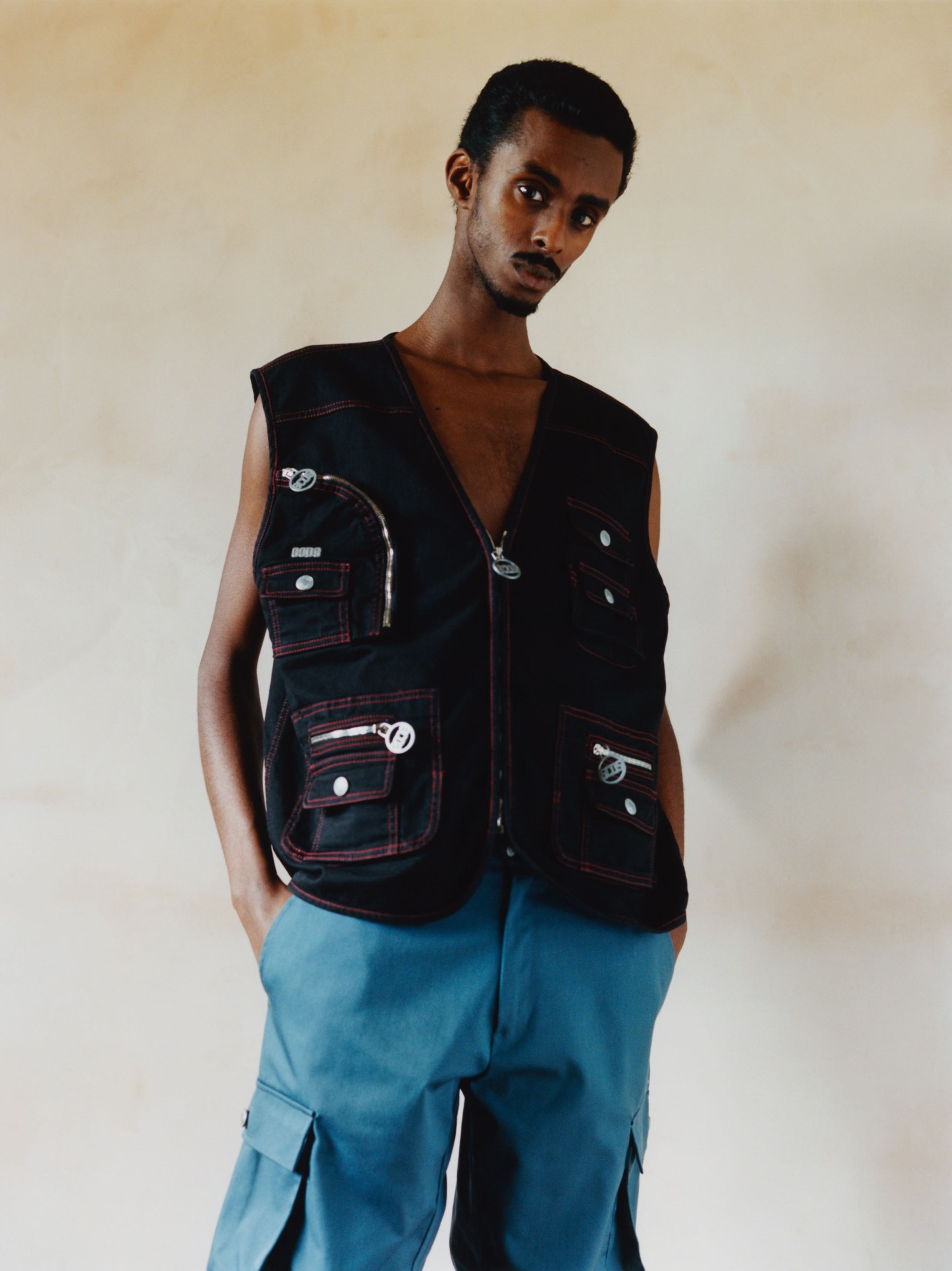

And yet, looking away from the catwalks of New York, London, Milan and Paris, and looking across the globe, a new wave of streetwear has been emerging. From Singapore to Lagos, from Greece to Eastern Europe a generation of talented kids are turning to streetwear’s open template to create fashion that reflects their personal lives and realities, it is fashion that represents the progressive politics of 21st century youth, the inclusive attitude of a generation raised in communities fostered and developed online.

In 2015, after the terrorist attack at the Charlie Hebdo office in Paris, France witnessed a surge in anti-Islamic hate-crime and violence. In response Theodoros Gennitsakis started up the clothing label Pressure with a desire to counter the negative stereotypes swirling around Arabs in the country. The first piece he created was a simple T-shirt with the word “pressure” written on it in Arabic (aping Supreme’s red-on-white box logo for added impact) “because of the pressure Arabs in France were feeling at the time,” he explains. “The pieces are simple but the message is strong.”

Pressure has now evolved into a dedicated clothing label but it remains rooted in that initial creative idea. “The goal was to create a feeling and a story, the product comes from that.” The product reflects a modern European story, a crashing together of cultural references from across the continent, slogans are written in Arabic and Greek and English, the symbols and motifs drawn from the ancient and modern mythologies of these cultures. Pressure’s cross-cultural synthesis suggests a pan-European pan-racial positivity, a utopian union, the Med as a space of integration rather than division.

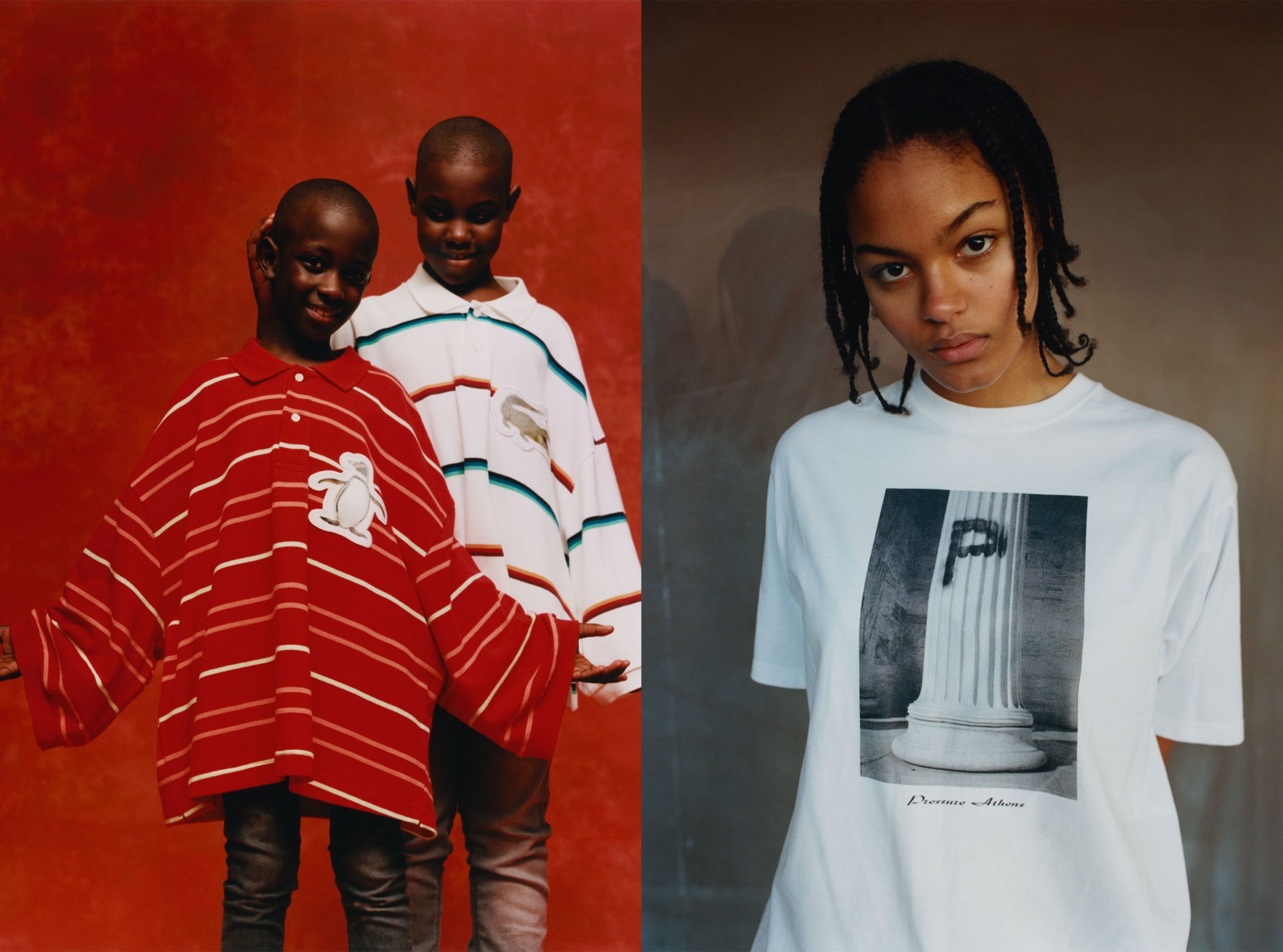

The pieces Pressure create are bold, colourful, simple, fun, communicative, and they utilise the simplicity of streetwear to make a big statement. Theodoros has seen the brand get taken up by everyone from fashion IT kids to old dudes into politics. But Pressure is also indicative of a new feeling in fashion, an openness to diversity, an inclusiveness, a new attitude. Streetwear is the easiest mode for channeling that expression, especially for untrained youth who didn’t go to fashion school. “The children of immigrants working in fashion are the most exciting thing right now, pushing their roots into the industry. Street culture made this moment because most of these kids came from the street.”

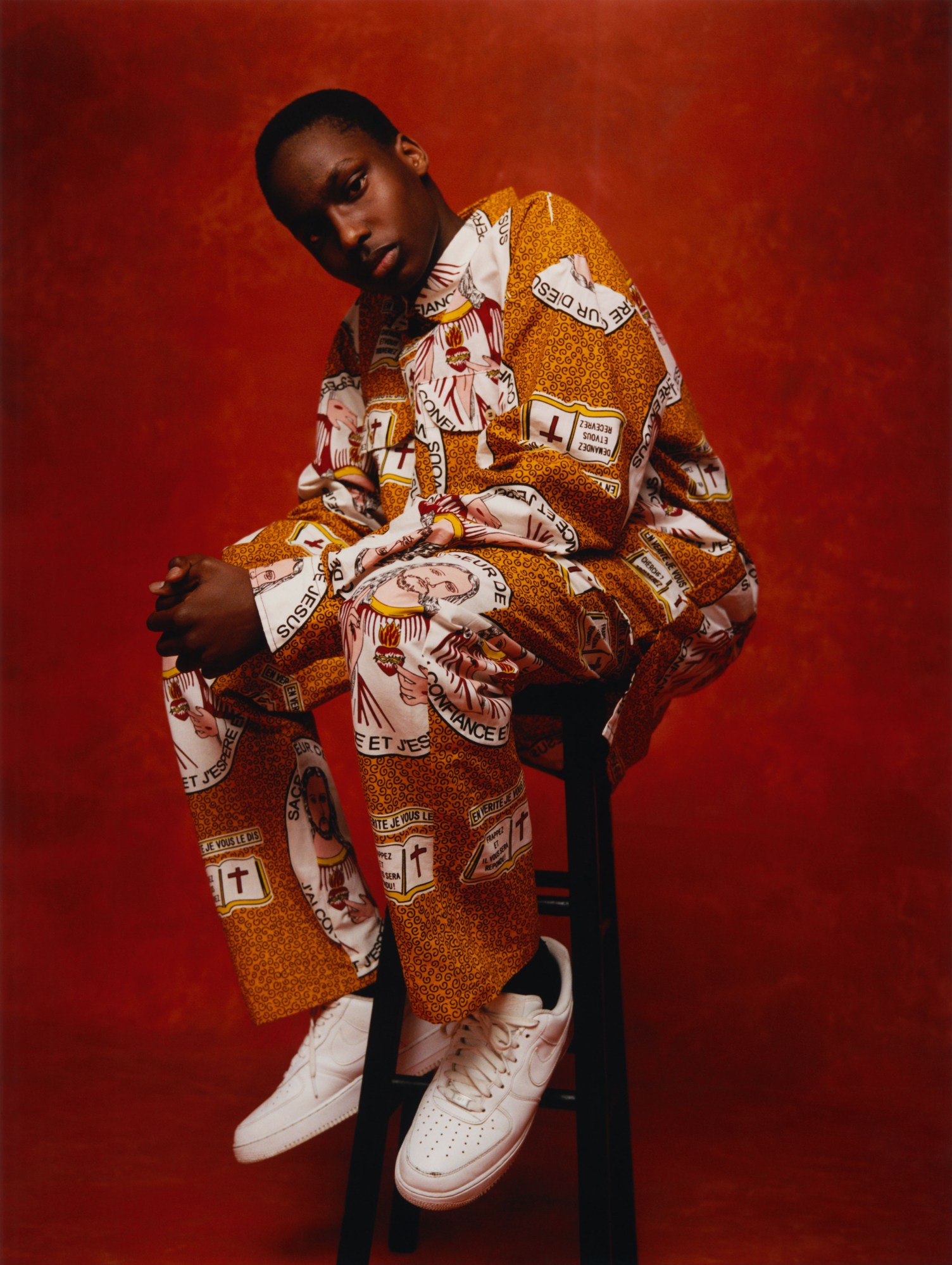

Nigerian streetwear label Wafflesncream are engaging in a similar cultural crossover. It was started in 2012 by Jomi when he moved back to Lagos – he’d got into skating whilst living in Leeds, and in the truest of streetwear moves, created what they wanted to see in the world. What they do is analogous to brand’s like Palace or Supreme, but run through with a Lagosian POV. “We’re designing for our aunties and uncles, mums, dads, pastors, priests, homies, our community, our environment,” they explain. “We’re just telling our stories and having fun. Showing the world the world we live in and how nice it is.”

Which is really the crux of this whole global movement, what streetwear has enabled for a generation of designers with something to say, but who are maybe not professionally trained. There’s a beautiful democratic openness to it all. You can start a label if you want to. The barriers to creation don’t exist anymore. We all have Photoshop and can bulk buy Fruit Of The Loom T-Shirts. You can get yourself out there via Instagram. All you need is something to say. “You already possess everything you need,” Youths In Balaclava, a Singaporean fashion collective, explain over email. “We had to sacrifice our savings to make our first collection but the desire to create was too strong, we wanted clothing we could call our own. Our inspiration comes from everything we experience in our everyday lives, we’re always looking, always noticing.”

Not that much necessarily unites these brands beyond this ethos, this DIY spirit, this desire to represent their lives. Streetwear at its heart is as an ideology as much as a fashion style, and some of the most exciting developments in that ideology have been happening in the land of streetwear’s birth, Los Angeles.

An axis of Some Ware, Come Tees and Online Ceramics, all more or less T-shirt brands formed by a cross-section of artists-musicians-designers, exist in the city. They are exciting because they are using this most basic of garments as a way of expressing progressive political ideals, but also because they approach this garment with the electric creativity that the couturier approaches the finest silks and satins. “I try to have as much complexity and content as the simple form of the T-shirt can bear,” Sonya Sombreuil of Come Tees explains. It’s something that might as well stand in for the whole scene. “I consider myself to be primarily an image maker,” she continues, “And my images contain my hand, my authorship, which I think is different from a lot of brands. Because of this limitation I try to keep the ideas, techniques and references as nuanced as possible.”

There’s an undeniable fashion craft to what these LA labels are doing, which is why the ‘regular’ fashion industry has taken note of them, but the industry came to them, rather than the other way round. They favour self-expression and the home-made, DIY artsyness – they have punk roots and a new age purity. “Sincerity and creativity” according to Online Ceramics, are what unites and drives them. “We’re all artists doing our own thing, and being accepted as ourselves into the fashion world.”

A lot of this springs from these brands’ roots in the DIY punk world. They have a political ethos that stems from that. Their “own thing” is progressive, pure, inclusive. Some Ware, for example, have engineered their garments with the purpose of working for all bodies, all genders. Indicative of Some Ware’s politics is their recent Election Reform project, created with Tremaine Emory of No Vacancy Inn, to encourage streetwear fans to get out and vote by offering them free tees in exchange for proof of casting their ballots.

It’s a gesture that goes a long way to explain what underpins this nascent and exciting scene. The success of these brands, despite existing outside of the traditional fashion orbit, also goes someway to show just how fashion is changing. Or at least, that there is an appetite for change.

“All these historical structures are disintegrating,” Sonya explains. “Fashion seasons, brick and mortar shops, the American marketplace… My favourite moments are when someone from the underground gets to operate at the apex of high fashion.” Which is where we are – underground fashion at the apex of high fashion, and now we’re seeing a new underground, a global underground, come of creative age.

Credits

Photography Maxwell Tomlinson

Styling Max Clark

Grooming Gary Gill at Streeters

Set Design Sophie Durham

Photography assistance Meshach Roberts, Kerimcan Goren and Rory Cole

Styling assistance Louis Prier Tisdall

Hair assistance Tom Wright and Chris Gatt

Handprints Labyrinth Photographic.

Casting Gabrielle Lawrence at People File

Models Marco and May at IMG, Fox, Skinnyman, Yasin, Narayin, Tyson, Tiago, Aljab and Jessica.