Stretched across the ceiling of a chapel-like gallery in the Brooklyn Museum is the painter Kehinde Wiley’s 2003 large-scale panel Go. It’s a mural of young black men, floating through a blue sky scattered with large cumulus clouds, wearing our era’s streetwear: baggy blue jeans and oversized T-shirts, bomber jackets, Timbs, and Air Force 1s to perfectly match the backwards fitted caps on their heads. One figure, body crawled inward, eyes wide and wandering, appears weary. His head, encircled by an ornate doily-like gold halo, is covered by a shimmering sign of black protection, style, and beauty: the du-rag.

Go, and later Wiley’s Tomb of Pope Alexander VII Study I of a black figure wearing a white du-rag, are the first works of art I remember seeing where a figure sports a du-rag. The du-rag has its roots in the decorative headdresses of sub-Saharan Africa and subsequently, the rags American slaves used to tie their hair back in the the field and on Sunday morning to praise God. During the Harlem Renaissance, the du-rag (sometimes made of women’s stockings) began to be worn by black American men inside their homes to protect their hairstyles. Into the latter part of the twentieth century, they were used by men of the diaspora to create waves in their fades and to protect their cornrows while they slept.

By the 1990s and early 2000s, it became a fashion accessory for young black men, worn outside in the world–despite the protests of many black parents, who wanted to protect their sons from easy stereotyping– as a point of self imaging, black cool, and a gesture of their own representation. Rappers like Nelly and 50 Cent wore them in their videos and on red carpets and basketball players like Allen Iverson stylized them off the court. These men were owning their blackness in a whitewashed world.

The trend was short-lived. The culture has largely moved beyond waves, as a hairstyle, and the du-rag, as a signifier of black male personal style and marker of masculinity. But recently, it has re-emerged in both fashion and art as a powerful symbol of self care and individuality.

It was arguably Rihanna who brought the du-rag back to the fashion world of late, including it in her Fenty Puma spring/ summer 17 collection. The pop star-cum-designer refashioned the utilitarian headdress in soft shades of lilac, olive, and pink stretch lace, giving it a feminine bent.

Artists are also finding inspiration in the humble garment today. Kevin Beasley’s Chair of the Ministers of Defense, an installation of altered jeans, T-shirts, housedresses, and du-rags, surrounding a 1970s vintage wicker “peacock” rattan chair, is currently on view at the Hammer Museum in Los Angeles. The piece alludes to both Gian Lorenzo Bernini’s seventeenth-century altarpiece for Saint Peter’s Basilica in Rome and the iconic 1967 photograph of Black Panther Party founder Huey P. Newton wearing the party uniform while holding a shotgun and a spear in a peacock chair. The du-rags and other garments are covered in resin and adorned with guinea fowl feathers and Maasai and Zulu war shields, and hung by the artist in a way that suggests they are black figures guarding a throne.

“I was trying to consider in material choices how can the objects that I’m familiar with in my personal life, be elevated,” explains Beasley. “The du-rag for me becomes one of the most interesting garments because it’s been relegated to present a very particular stereotype and image of black men.”

The du-rag outside of the black community has become, as Brian Josephs’s recent GQ essay argues, “criminalized,” loaded with stereotype as a symbol that suggests the black males who wear them are menacing “thugs.” Josephs notes that both the NFL and NBA banned the “$2 dollar piece of headwear” in the early 2000s. Historically black colleges including Hampton University have banned the du-rag.

“They’re a major asset to the black community hair self care image,” explains Beasley, “I think in some way [Ministers] is about reclaiming the potential and even possibility in what they are and allowing them, as an object that has a lot of power, to exist very prominently.” Beasley, who has used the du-rag as source material in other works like the sculptureUntitled (Dome) and the performanceYOUR FACE IS/IS NOT ENOUGH, says,”They’re elegant.”

The portrait series Du-Rags, by New York photographer John Edmonds, features close-ups of the back of young black men’s heads covered by these “objects of adornment—like a crown, hijab or burqa.” “Du-Rags are very black,” explains the artist, who recently completed an MFA in photography at the Yale University School of Art. When Edmonds was growing up in Southeast D.C. in the 1990s, he, his mother, and many of the men and women in his neighborhood wore du-rags. That early universality made him see the piece as a comment on black gender expression. “I don’t really understand them as being gendered or prescribed to men, like many people do,” he says. Untitled (Du-rag 3) is an image, printed on silk fabric, of a black male with a Cerulean blue du-rag tied neatly around his head. For Edmonds, it represents an opportunity to consider the individual as a universal black body without the limitations of gender.

Edmond’s use of the du-rag to deconstruct gender and sexuality echoes its depiction in Barry Jenkins’s black queer coming of age film Moonlight. Chiron’s black du-rag is one symbol among many that subtly communicates how his queerness clashes with traditional notions of black hyper-masculinity. A sign of how intersectional identities often clash.

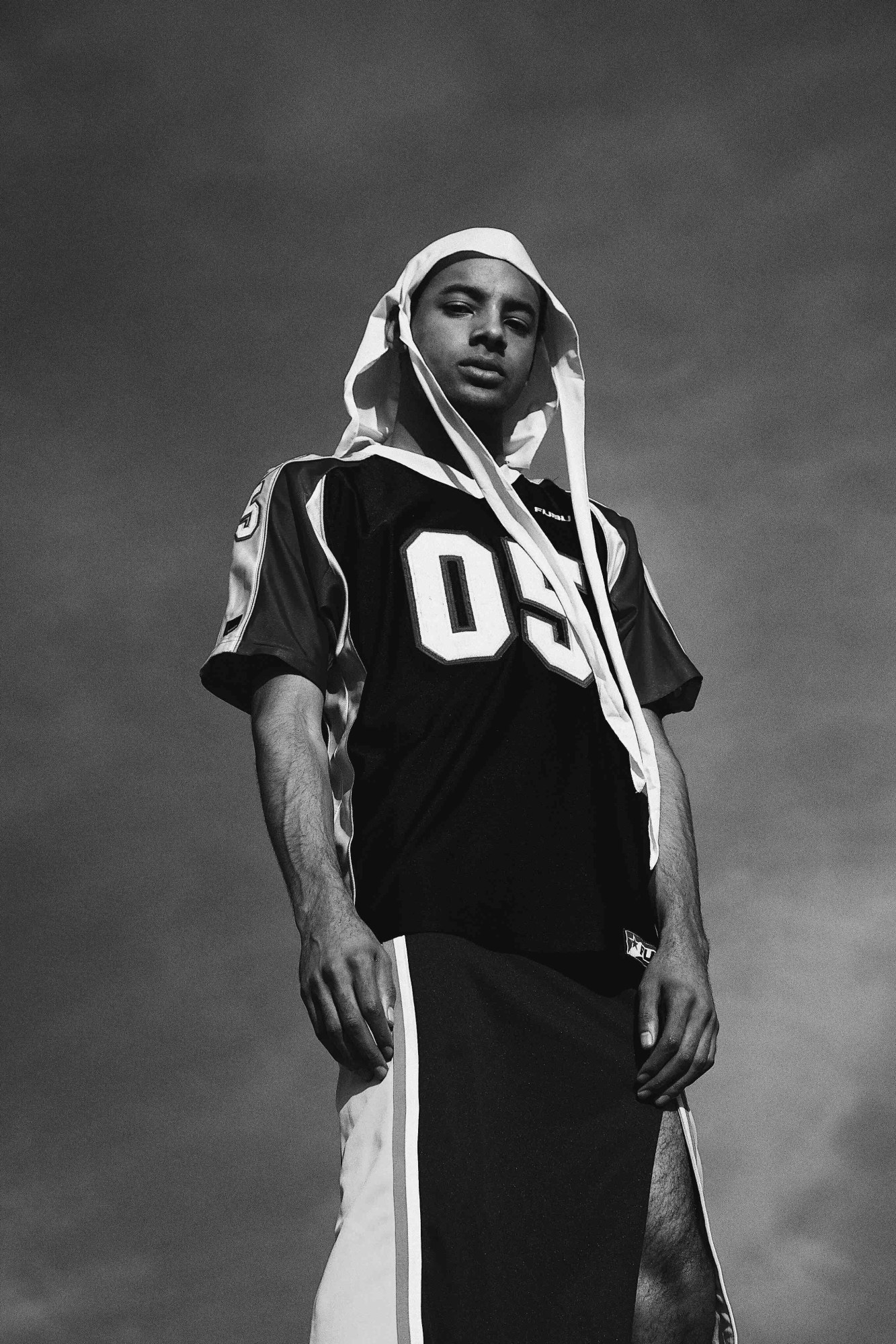

Reinventing the du-rag’s ties to sexuality and gender performance are also themes that animate DU-RAAAG, a fashion photo project by Los Angeles artist and SON publisher Justen Le Roy. The black and white images, shot by Russell Hamilton, of black boys in the desert wearing du-rags and styled androgynously, “represent the du-rag as a cultural headdress that is synonymous with the black experience, mostly represented by the black male body,” says Le Roy.

Le Roy’s work reclaims images of the du-rag as depicted by mainstream fashion designers like Rick Owens, who sent white male models down his fall/winter 14 runway wearing black and brown du-rags. Kylie Jenner, evoking rapper Eminem who wore them throughout the early 2000s, donned a white one during New York fashion week last September, which, for Le Roy and others, represented cultural appropriation. “The du-rag is automatically criminalized for being of use to the black body yet we’ve seen platforms praise it as an aesthetic when presented on non-black bodies in fashion and music,” he says. “These portraits put those who understand the history and use of the du-rag at the forefront.”

The, non-commodified, ritualistic history of the du-rag is sublimely captured in the photographer Micaiah Carter’s Orchestrated. The smoky portrait of a young black male, having a du-rag tied around his head by another, illustrates how the headdress represents community and coming of age. “Growing up in high school, no one really understood why I put a du-rag on my head at night,” explains Carter. With Orchestrated, he says, “I wanted to put back in context what putting on the du-rag means,” for the black community. This appears to be the goal of many of the black artists and creatives reclaiming its symbolism.

Credits

Text Antwaun Sargent

All photography courtesy the artists

*Kehinde Wiley, Go, 2003

Oil on panel, Each panel: 48 x 120 x 2 1/2 in. (121.9 x 304.8 x 6.4 cm). Brooklyn Museum, Mary Smith Dorward Fund and Healy Purchase Fund B, 2003.90.

© Kehinde Wiley. Courtesy Sean Kelly Gallery, New York

*Kevin Beasley, Chair of the Ministers of Defense, 2016

Resin, wood, acoustic foam, jeans, trousers, du-rags, altered t-shirts, altered hoodies, guinea fowl feathers, wrought iron window gate, vintage Beni Ourain Moroccan rug, kaftans, housedresses, Maasai war shields, Zulu war shields, 1970s vintage peacock rattan chair

154 x 162 x 84″ / 391.2 x 411.5 x 213.4cm

Installation view, Hammer Projects: Kevin Beasley, Hammer Museum, Los Angeles, January 21 – April 23, 2017. Photo: Brian Forrest, Courtesy the artist and Hammer Museum, Los Angeles