The Great Frog is the ultimate emblem of rock and roll. Established in 1972, to purchase one of its sterling silver skull rings — the original sterling silver skull rings, might we add — is to purchase a one way ticket to a world of outlaws and rebels, outsiders and misguiders. Little wonder it’s become the mythmaker of choice for everyone from Slayer to Led Zep, Motörhead to Iggy Pop.

While rock and roll has, in recent years, become little more than an £8 Rolling Stones T-shirt from Sports Direct, The Great Frog has managed to pull off the impossible. Avoiding the shameless snare of Jack Daniels cliche, it’s turned what was a single London shop, tucked just off Soho’s Carnaby Street, into a genuinely cool global brand. One that feels as much at home collaborating with Dover Street Market as it does with Iron Maiden, supplying rings to Kate Moss, Post Malone and Gigi Hadid from stores in LA, New York and New Orleans.

With its latest outpost, the Brinkworth-designed Shoreditch store, now open to the public, we spoke to Reino Lehtonen-Riley, The Great Frog’s creative director and son of the founder Paterson Riley, about the pride, glory, heroism and attitude behind the name.

What are your early memories of the shop when you were a kid?

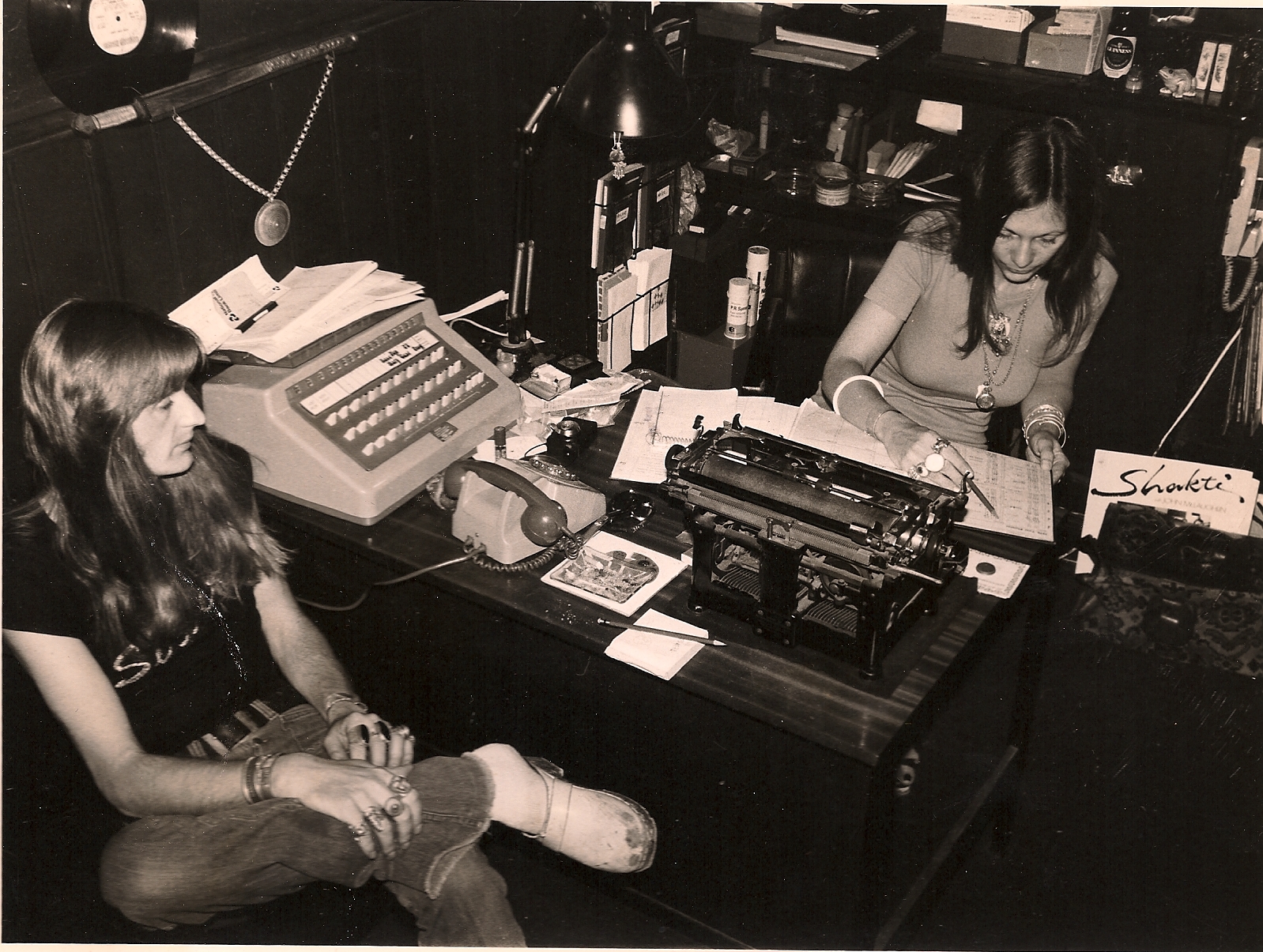

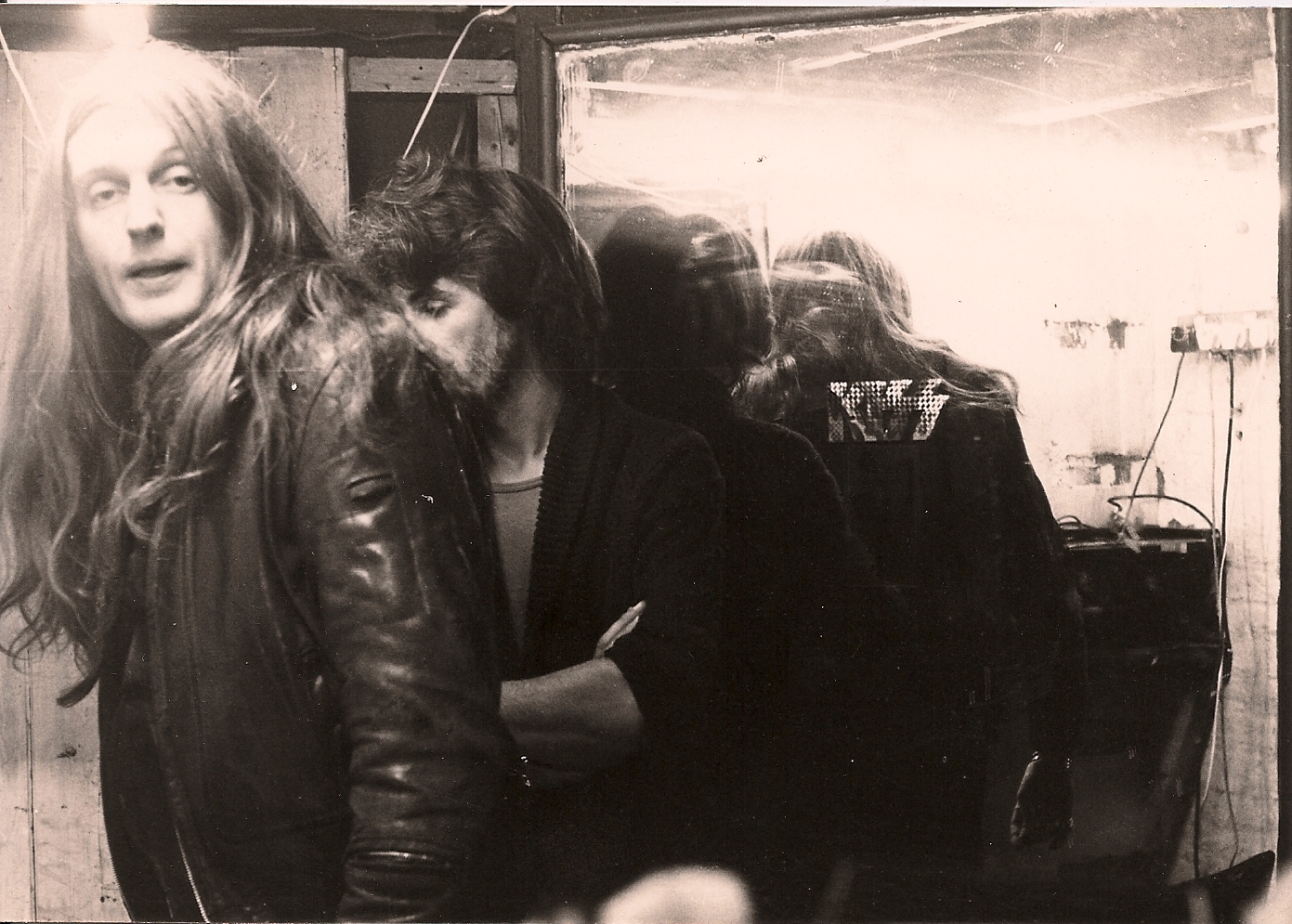

I mean, it was kind of strange. My parents started off having a shop in Wimbledon. It was a bit of a squat and they sort of had a shop front there. And it got demolished, so my mum campaigned for them to give us some money to get a new one. They found one in Harrow, and for some reason they decided it would be a great place to sell rock and roll jewellery. So we had this great big shop with a house above it. Basically a place for them and all their mates to hang out in, get wasted. It had the workshop and the shopfront and about ten floors with all sorts of people. There’s be drummers from Africa, Hells Angels, rockers, drug dealers from Morocco selling hashish. It was this really kind of Wes Anderson upbringing that I was deeply embarrassed about at the time. Growing up in the suburbs you just want to be a normal kid. And if you get sent to school in snakeskin cowboy boots and a leather jacket, dropped off on the back of a chopper it’s like literally the most embarrassing thing that can happen. Now you can look back and think it sounds quite cool. But back then you just wanted to look completely normal, not have your parents driving to school in a hand-painted hearse.

You didn’t want to be part of the company when you were older, then?

I wanted absolutely nothing to do with it! I was adamant. You know how kids want to rebel against their parents? There was literally nothing I could do to rebel. So what I did was become pretty square. I did an engineering degree. I’d wear a button-down Ralph Lauren shirt with chinos and loafers. And my dad was just like, I can’t believe my son has turned out like this. But that was me rebelling, doing the opposite. The music I was into at the time was hip-hop and he’d just shake his head at the shame of it all.

How did you come to be involved?

Well, from an early age, my dad had me on the bench, learning jewellery. So I had the skills. Then I went to university, did my engineering and product design degree. After I finished I got a job working for Armani in Australia. So I got a bit into the fashion side of things. And while I was over there, my dad phoned me up and said the business was bust. They were in trouble, had no money left. This was the early 00s, but it had been on the rocks for years. He owed a lot of money to the banks. So he said ‘can you come back, I need help moving out of the shop because the bailiffs are coming’. So I flew back over to London and started chatting to him. And I realised it is a family business and it was something that I wanted to be part of. I looked into it and realised that the money owed wasn’t a huge amount. And I just thought if we went to the bank and pleaded with them and I took on the name so it wasn’t my dad’s credit, then there were loads of things we could do. So we thinned everything out, got it down to just me and my dad and really skeletal staff. We got rid of the stock and redefined it. Because there were some great things about the brand. And I thought if we could get rid of the last ten years then there was a lot there.

Did you have a vision for what you wanted to do?

Not initially, no. Basically there was a lot wrong with it. There would be imported jewellery from India and crystals and that sort of stuff. It looked like a secondhand Camden market sort of thing. And I’d go into the basement where my dad had his record collection and there was no work going on, just loads of ashtrays and booze bottles lying around. But it had a great essence and there was some cool stuff. I’d go through these old magazine articles and think, this is fucking great. There are all these great pictures and stories, but they’re not being told. So in terms of direction, it was strip away all the crap stuff, hide the sort of lost 90s period, and go back to when it was really cool and current. I’d pull stuff out and go, ‘Dad, what’s this?’ And he’d say, ‘Oh, yeah, Bruce Dickenson wore it on stage at Wembley.’ I was like, fuck! We need to get this out there. I made a few stupid moves too. I didn’t know about licensing deals so we relaunched a load of Iron Maiden and Motörhead stuff, because my Dad bought Lemmy a pint in 19-fucking-81 one and he said it was fine to sell them. Of course, as soon as we relaunched them we got cease and desists. But they liked what we did and invited us in for a meeting. Next thing we knew, we were signing merchandising deals. So there was never a grand master plan. A lot of it was just accident and hard work.

And the people who wear it have really changed over the years too, right?

Yeah. I mean, it used to be when you’d go to Carnaby Street and you’d be sitting outside the shop, you’d know when there was a Great Frog customer walking down the street. They’d be a goth or a biker or a metaler. And now everyone’s wearing it. Before it was seen like you were an occultist. People used to cross the street from the shop. We’d have people holding crosses and bibles protesting.

What are your hopes for the new store?

With the Shoreditch store, I kinda want it to show the business as a whole. We’ve got the workshop downstairs where people can see it and view it and understand the jewellery isn’t shipped in boxes from China. It’s handmade. We’ve got a coffee bar, we’ve got seating. I want people to come in and get a feeling of the energy. It’s gritty, dirty, hard work making jewellery. It’s not all pretty. And you kinda want people to have some investment in it. Investment in the Great Frog world.

The Great Frog Shoreditch is at 1 Holywell Lane, London. A new collection, Lock Down, launches this week. For more information visit www.thegreatfroglondon.com.