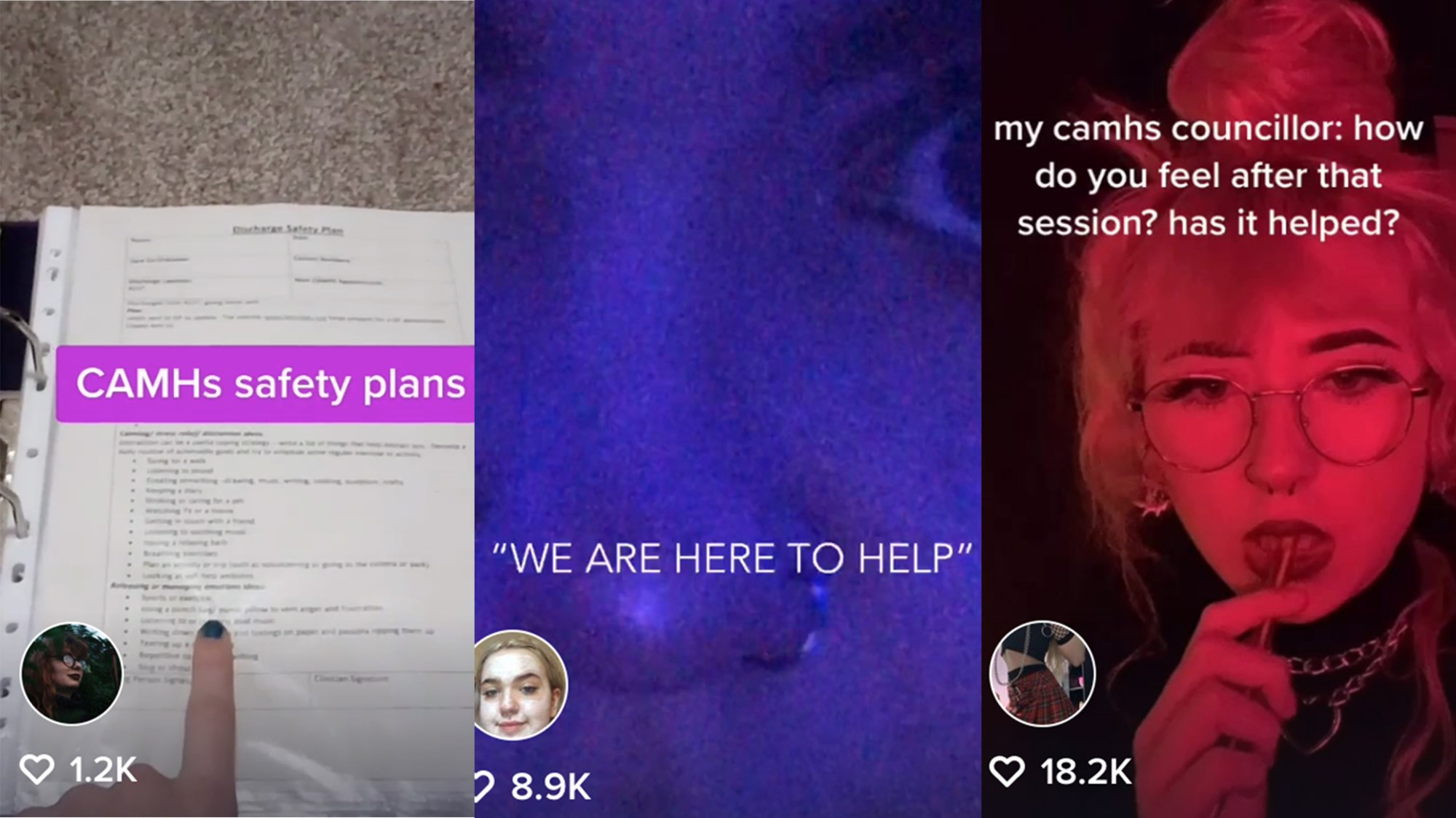

For most of us, TikTok is known for some largely pretty silly — albeit hilarious — stuff. There’s the cursed memes, the dancing ferrets, the dance challenges, that weird content where someone roleplays as a stranger who sits next to you in class… But the app is also being used as an important springboard for discussion. Along with providing a platform for young Muslim women to speak out about Islamophobia, and LGBTQ+ people to discuss coming out to their parents, there’s a whole subgenre emerging where teens are speaking out against the failings of mental health services.

Videos with the hashtag #CAMHS – standing for child and adolescent mental health services – share between them 6.1 million total views. #MentalHealth has 85.8 million. What those millions contain is a legitimate and extensive online community.

In typical TikTok style, the issue is approached with a tongue in cheek, absurdist approach. The videos are simple, funny and angry. One features a girl dancing to Lorde’s “Royals”, captioned “me aged 16 explaining all my problems and trauma”. The dancing stops and the caption changes to “CAMHS:” in time for the punchline: ” we don’t care”. It has nearly 23,000 likes.

In the comments, people are inspired to open up about their own experiences with mental health care. “They told me I had ‘a great family life’ and to ‘drink more water’,” one comment reads. “I was straight up told to ‘not focus on feeling bad’ when I was talking about my depression,” says another.

The original video is from Autumn, a 22-year-old from Lincolnshire who’s suffered from mental health issues for ten years. For Autumn, TikTok has proved to be a good distraction when she’s down. “When I’m feeling low, I’ll pop on a bit of make-up, force myself to get dressed, and think to myself ‘I’ll just make a relatable video as a coping mechanism’”. With 11,000 followers, Autumn’s content is clearly striking a chord with a lot of people.

15-year-old Hayden is another TikTok producer using the platform to sound off on mental healthcare. In his video, background music gets progressively more distorted as the list of “bullshit” gets more ridiculous. It starts with “Everything is confidential” before climaxing with “pRaCtiCe MiNdFullneSs”. Comments include “TRUE TRUE TRUE” and simply “yes”.

Although he’s suffered with mental health issues for the past five years Hayden, from Nottingham, has only been using TikTok to talk about his mental health for around three months. “I was scared of opening up,” he admits. But on TikTok he has found a community, a “good safe space”. He even finds that viewing other mental health videos can help calm him down.

While this has spawned a community of supportive, like-minded people, the discourse is — naturally — not perfect. TikTok mental health content can be, many users tell me, triggering. Another issue is the fickle nature of online fame that comes with creating semi-viral content. “Because I have a decent amount of followers it’s hard to think people will be friends with me for any other reason,” says Hayden. “They only want to be my friend because of the TikTok popularity.” With 19,000 followers on an app where clout reigns supreme, he may have a point.

Author and mental health expert Beth Burgess agrees. Though she acknowledges that entering into an online community such as this can be a validating experience, the reality is that TikTok content remains largely superficial. “Young people may be looking for connection and support by sharing content on TikTok, but I’d question how real any support they get will be on this kind of platform. Overall, social media is more focused on attention-getting and image than it is on true connection.”

Beth may be on to something, but clearly for some people the experience is not a wholly shallow one. For every creator chasing likes through dark humour, there are those finding solace, support and community on TikTok. “Young people often use creative forms, such as music and humour, to both express themselves and make sense of the world”, Beth acknowledges. And it’s certainly something that rings true for 18-year-old David, a Pennsylvania native using TikTok to sound off on his experiences with depression and anxiety. With over 214,000 followers, David often posts about mental health, using his platform to open up important discussions. “[TikTok] gave me a place and a voice to talk when I was holding everything in,” he says. “People are always there for one another.”

Autumn, now 22, only got her borderline personality disorder diagnosis last year – but having suffered since she was 12, why did a diagnosis take so long? “I think there are some who look at it as though some people are attention seeking, or that they’ll get over it,” she speculates. (NICE guidelines state that borderline personality disorder symptoms cannot normally be formally identified before 18). Though refreshing to see such candid discussion of a stigmatised subject, the rise of TikTok as a platform to attack mental health services based on individual experiences belies deeper issues of government and institutional underinvestment.

Clinical psychologist Dr. Nicola Green has worked with CAMHS for over 15 years and is aware of this TikTok trend. She warns of the dangers of the community potentially putting off other young people from even trying to access CAMHS in the first place, but does believe that TikTok can be a good way to express yourself. “I think it is a good thing that young people have outlets where they can connect with others who may be experiencing similar things,” she says.

In terms of moving forward and addressing these complaints, Green calls for a systemic shift. She says that while adolescents may be referred to school counselling instead of a specialist CAMHS team, “it is not good enough that young people are experiencing this as not being heard or taken seriously.” She is aware that change is needed. “We have more work to do to ensure that this changes and that the whole CAMHS system works together to support the emotional wellbeing of adolescents in our care.”

It’s no secret that many of the issues CAMHS face stem from chronic underfunding – an issue compounded by the fact that adult mental health investment has traditionally been prioritised due to the economic impact of missed days of work. You need only glance at the comments beneath these TikTok videos to see the visible effects of an overstretched NHS. Comments such as “I’ve been on the waiting list for months” are disturbingly common. They aren’t unfounded: according to NHS statistics, in 2017 one in five suffering adolescents reported a wait of over six months to see a specialist. And that’s only if you get to a stage where CAMHS take you on – the Education Policy Institute recently found that over a quarter of referrals to children’s mental health services were rejected between 2018 and 2019. Although CAMHS are the target of these videos, the fact is that it’s a legacy of Tory austerity and a chronically underfunded NHS which should be the real target of ire. What TikTok does offer though, is a look into what it’s like to experience the cripplingly underfunded system first-hand.

Given that your first experience of mental illness can often be scary and overwhelming, and that the system isn’t set to change any time soon with another four years of austerity on the horizon, it’s great that TikTok is allowing this community to blossom. Autumn says that when she was a teenager she felt isolated by her early experiences of mental illness. But now she finds comfort in knowing that she’s doing her bit for young people struggling for the first time. She’s continuing to make TikTok content for fellow mental health sufferers and is considering branching out to start a YouTube channel. “It’s great to be able to make others realise that aren’t going through things alone.”