Teenage suicide, bullying, and depression aren’t themes you’re used to seeing in anime. And sure, how could something so complex, so multi-faceted, be rendered in two dimensions? Well, here’s proof that it can.

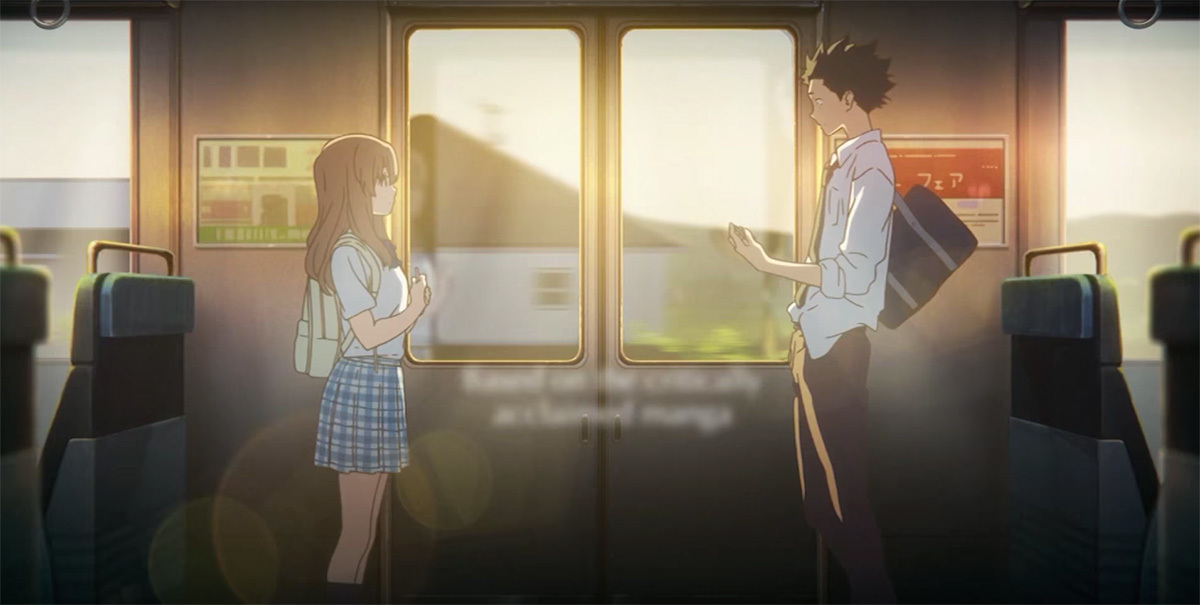

A Silent Voice, adapted from the wildly popular manga by Yoshitoki Ōima, is about a teenage boy, Shoya, desperate to make amends for bullying a deaf girl back when he was a hot-headed punk kid. Directed by Naoko Yamada, the anime packs an emotional gut-punch as it depicts the life of a depressed teen who can barely look people in the eye.

The film’s release follows the crazy success of Makoto Shinkai’s body-swap anime Your Name. In fact, A Silent Voice opened behind that film at #2 at the Japanese box office, with early signs suggesting it’s going to be another smash. So are we entering a new golden era of anime that swaps demons and spirit animals for teens saddled with emotional baggage? We sat down with A Silent Voice director Naoko Yamada to see how she tackled such issues in two dimensions.

Read: Your Name is the smash hit Japanese anime about body-swapping teens.

A Silent Voice started life as an insanely popular manga. Was it easy for you to envision it as a film?

Yeah, in a way. But it was difficult in other ways, because everybody has an impression of what it is like. So I really had to deconstruct the impression that many people had of it, and reconstruct it as a feature film. I had to find new angles.

Were you nervous about meeting fans’ expectations?

I was very nervous, obviously, but I deliberately didn’t dig into it, I didn’t do any research about fans’ impressions or anything, because as a director I wanted to be honest to what I felt about the story. And also my impression was more important to me than expectations. I had quite a lot of meetings with the author, Yoshitoki Ōima, so what I had to do was convey her passion and the essence of the manga.

How did you approach the delicate issues around depression and suicide, given that you’re working in two dimensions?

Yes, these issues are very delicate and I had to be quite sensitive and cautious about it. But what I really wanted to avoid was making all of that look funny or making these things overly sensational or dramatic. I wanted the audience to feel for each character — and yes, I was very cautious about that.

And yet, it is funny too, with the goofy sidekick character providing moments of light relief…

Yes exactly — him and also Shoko’s sister Yuzuru. They were a nice counterbalance to the darker side of the story.

Could you personally grasp the issues in the film?

The themes were there but it’s not from my personal experience at all. I wanted to be fair. I didn’t want to be judgmental anywhere.

Did you look into bullying in Japanese schools?

No, because… obviously the bullying bit is important, but in the bigger picture for me, it was not the most important aspect of the film. So I didn’t think I needed to get details, I didn’t think that was necessary.

So what was the most important aspect?

Emotions, human emotions, and connections with other people. For me it’s about what’s inside everyone. You want to be understood but you’re always misunderstood, so you want to say “I love you” to someone but you can’t quite do that. You want to be wanted but you don’t know how to do it. So the importance of what you’ve got inside that’s not necessarily shown outside.

The decision to have literal crosses on characters faces (as seen from the protagonist’s perspective) was a bold move. How did you come to that?

That was in the manga so I just had to follow that. And also the author requested it, she wanted the crosses on the faces. And I thought that was really cool visually and would express what Shoya was thinking.

Did you change much from the manga?

There are actually a lot of minor changes, but the major ones: a huge episode was cut out where that sidekick guy wants to be a film director and he makes a movie. That wasn’t in the film. That was difficult because it was quite important in the manga, and I expected fans would like to see it. I didn’t want to let them down but I really wanted to leave it out without the fans really noticing it in a way.

Though it’s about teenagers, the film is handled in a mature way, with some distance. How have teens responded to the film and its themes so far?

I’ve had really good feedback from teenagers overall. I didn’t want it to be seen as a teenage movie for teenagers made by grown ups. But I’ve had really good feedback.

Was there anything you wanted to avoid?

I try not to have character templates, I don’t want blanket characters. And also, how to deal with negative emotions — I didn’t want to really stay with those negative aspects.

With the extraordinary success of Your Name, and now this, how do you feel about the future of anime?

It’s more sort of a hope for me. I’m in London promoting this film. I really think that we have all come a long way and it’s just a great pleasure that all over the world people are looking at Japanese animation films, and that’s just wonderful. So I think most of us creators are looking globally, we’re not just thinking of the Japanese audience. Hopefully it will happen, that more people will be watching good-quality Japanese animations. That will be a great pleasure.

You’ve worked in TV and film; what are your hopes and dreams for the future?

I’d like to do both. I want to do more TV and more feature films, but the projects I want to be working on are to do with human emotions, movies and TV shows that deal with basic human emotions, empathies, and sympathies.

Favorite anime?

Studio Ghibli [laughs]… All of them. I love them.

Read: These are the anime movies that perfectly capture coming-of-age. Put down the Larry Clark boxset!

Credits

Text Oliver Lunn