Headlight (d), 2012.

This article originally appeared in i-D’s The Family Values Issue, no. 347, 2017.

Wolfgang Tillmans is standing in front of a giant photograph, detailing in high-definition an ass and a pair of balls, and laughing. When pressed for an interpretation of the image, he says, with another laugh: “It’s just the facts of life.” One of his assistants is listening to the theme music from Indiana Jones in the background, the sounds of triumphant violins drifting in from another room, lending a surreal air to our discussion. It’s just over a week until Wolfgang’s second Tate retrospective opens, and in the galleries he’s busy putting the finishing touches to the show. There are assistants methodically working away on boxes of prints. There are pictures resting against the walls. Plans for arranging small prints plastered around the space. One room is still full of building materials.

p.p1 {margin: 0.0px 0.0px 0.0px 0.0px; text-align: justify; font: 8.5px Helvetica

The image we’re discussing is nackt, 2 (nude, 2) from 2014. Upon a deep blue carpet rest a pair of testicles, legs splayed slightly open, a semi-circle of ass cheek covers the top half of the image. It’s shot with the crystal sharpness and intense clarity that’s defined the artist’s recent work. Every hair is visible. Wolfgang states it’s not on display as a provocation, it’s simply “what we are. It’s free of charge and it doesn’t hurt anybody. To look at a butt and a pair of balls from this angle is not harmful, yet it seems completely scandalous. It’s very difficult to photograph nudity in a new way, but it warrants its place in the exhibition, or so it seems.”

It may surprise you that Wolfgang, for all his unflinching representations of everyday life, sex, dancing, love, and politics, is a photographer who gets easily embarrassed and has to overcome shyness to take even a clothed portrait, but especially to take a picture such as this. “It’s very embarrassing! Very!” he states. “That’s why there aren’t many nudes here. In the 2003 Tate Britain retrospective there were two penises in an exhibition of 350 photographs. Three reviews in the newspapers described the show as being “littered with genitalia,” but I very rarely take sexual pictures, or nudes, because I get so embarrassed.” So does his self-consciousness ever hold him back? “No, embarrassment is a good thing,” he states. “It’s a threshold you have to cross if you want to take a picture. Photography has to be painful almost. I have to want to make that picture so much that I have to overcome my embarrassment.”

Wolfgang’s second Tate show, simply titled 2017, is not a strict retrospective as such, more a survey of the work he’s created since his first Tate Britain retrospective, If one thing matters, everything matters in 2003. So there are no images of Alex and Lutz, no Concordes, no Deer Hirsch and none of those groundbreaking early images from i-D that made his name either, just 14 years of work by maybe the best artist-photographer in the world; densely beautiful abstractions, blown up black and white photocopies that revel in grain and noise, delicate and humanistic portraits and luxuriously detailed still-lifes. Wolfgang is, of course, rightly heralded and lauded for his work. In 2000, he became one of the youngest winners of the Turner Prize, as well as being the first non-Brit, and the first photographer to win too. He’s almost 50 now, yet still full of boyish charm and enthusiasm, his work still propelled forward by a genuine engagement in the world around him. 2017 feels like an apt title for the exhibition. If one things matters, everything matters might be a mantra for those of us trying to find ways into the beauty of Wolfgang’s work, defined by its lack of visual hierarchy and openness. 2017, then, is more about Wolfgang “looking for a sense of now” and “uncovering the state we’re in.” It’s the work of an artist uncovering the world around him.

The state we’re in, Wolfgang suggests, began in 2003, with the Iraq War and the massive global demonstrations against it. In particular the “wilful ignorance of the evidence,” that propelled us towards war, and “the disconnect between people and politicians,” when the protests proved unsuccessful in preventing it. It was an event that ended Labour’s post-Thatcher honeymoon years and proved a political millstone around the neck of a generation. “You know the whole ‘post truth’ thing that we’re supposedly living in now?” Wolfgang asks. “Back then that was something that drove me and concerned me very much, and that’s how the Truth Study Center projects came about.”

The Truth Study Center is a series of works arranged on mazes of overlapping narrow tables. It presents a constellation of fragments; newspaper clippings, emails, images, quotes, and pieces of text curated from 2005 to the present day. Truth Study Center is of course a tongue-in-cheek title, but the series isn’t about finding meaning in a confusing world. Instead, the alternative-facts and fake-news era we’re currently crashing through has put these works into stark relief. In response, Wolfgang has created a new Truth Study Center work for the retrospective that explores “the backfire effect” which is “the psychological effect observed in people who hold a belief that might not be supported by facts, and when they are faced with the facts about it, it will not change their view, but reinforce it.”

Politics is never far from Wolfgang’s work; something evident last year when he took an active and very public role in campaigning for Britain to stay in the EU. 2016 also saw him actively take a stand against Trump’s presidential campaign; utilizing his public platform to try and prevent the slide towards racism and nationalism we’re experiencing right now. But in the last two years Wolfgang has also immersed himself in his work as a musician. He was in a band in Germany in the mid 80s before he even picked up a camera, and recently returned to it, fronting a “traditional’ band,” called Fragile, and also embarking on an electronic project under his own name; one of his songs appearing as the coda to Frank Ocean’s Endless visual album. “I didn’t embark on all these projects last year because there was a stagnation or a vacuum in my art practice,” he begins. “The music just wanted to find a way out.” But even now, back “concentrating on the main thing I do” as he puts it. Politics and music are always inescapable for Wolfgang. In the exhibition itself, music finds form as a listening room dedicated to work of the 80s avant-garde pop group Colorbox. Part of his mission to get people to take pop music seriously as an art form, something he’s been pushing at his Between Bridges project space in Berlin. But music is there in many of his photographic works, 2017 features portraits of musical idols old and new, from Morrissey to the aforementioned Frank Ocean, through to images of clubbers lost in passion.

“In some ways I see myself as an amplifier,” Wolfgang explains. “It’s not the only role I have, but photography lends itself to amplifying things because it is a medium of mechanical multiplication. I felt from early on in my career that I could give physical space to ideas through my work. That was what my early work in magazines was about, in particular i-D. I wanted to use photography to give that space over to something I liked, like the peace movement. Or, for example, we’re sitting in front of this portrait of Patti Smith, a very unusual portrait because she’s being portrayed on a 15 meter digital screen at Glastonbury. To place that here is giving her space, giving Glastonbury space, giving what Glastonbury means to people in that space. Or the picture next to it, which I think will move by the time the exhibition opens, of six or seven people in intense conversation in a bar in St. Petersburg. It’s giving space to the very human act of talking to each other, instead of the act of buying designer handbags.”

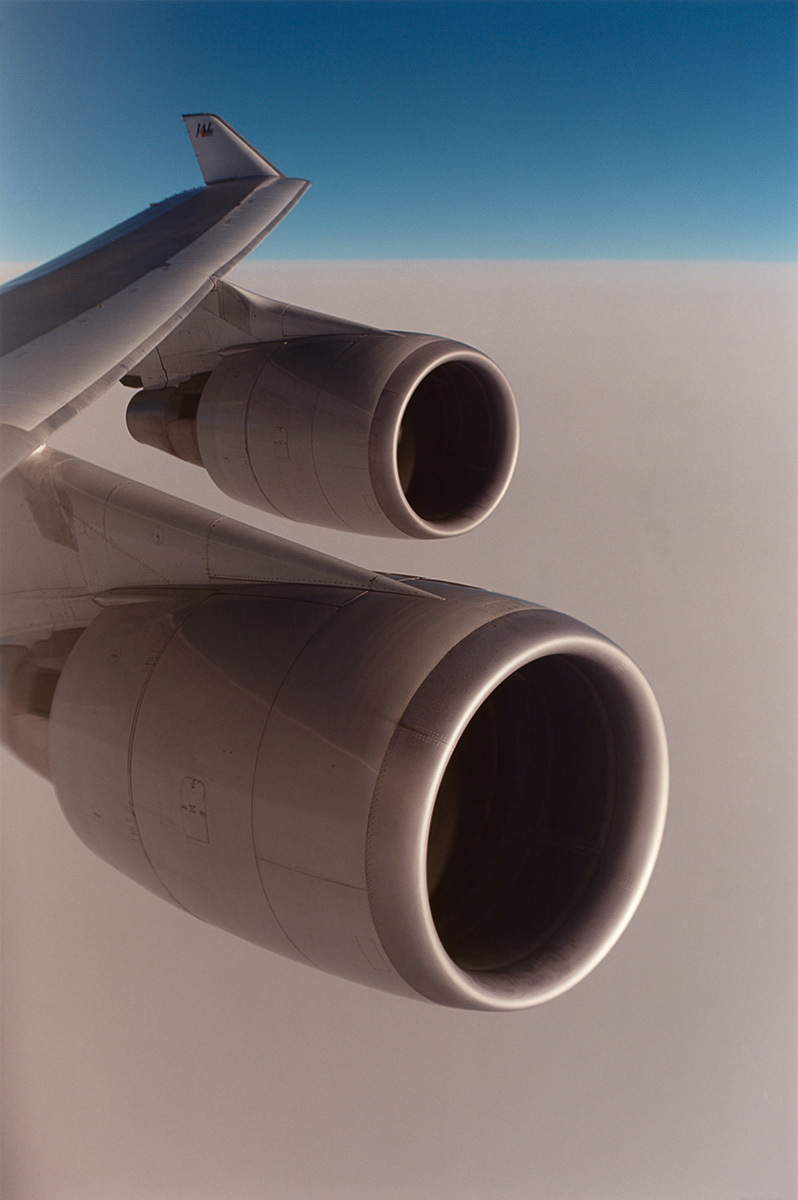

For all this talk of politics, music, and space, it’s easy to lose yourself in the beautiful imagery Wolfgang creates — even if he insists, “beauty is only a concept, a definition, something different to different people.” Specifically the large scale, super detailed photographic works he’s been creating recently. Wolfgang started using a digital camera in 2009, and stopped shooting analogue in 2012. One image that stands out from this recent period is a simple shot of a bright green weed sprouting out of concrete, captured in hypnotic high resolution. The detail these images capture gives them an almost 3D quality in the way they squash together depth and flatness. Another image, almost entirely white, called In A Cloud, was taken through a plane window as he flew through a cloud. “Every photograph is an experiment,” Wolfgang continues, whether it’s of a person, an object, wildlife, or the whiteness inside a cloud. “It was an experiment to see whether I could take a picture of it. People are afraid of using the most common subject matter — and that’s what I get accused of doing by some critics — but it’s really about seeing whether I can take a picture that captures the nature of something, but also the very specific feelings of that moment, in this time, in this place.” It’s this that lends such simple subject matter such resonant emotion, such depth, beauty, and visual complexity.

It’s hard to describe what gives Wolfgang’s portraiture its essence, its Wolfganginess. You can recognize his work a mile off, somehow. There’s a humanity and simplicity to the way he captures people. There’s no trickery, no showy concepts, just an image that captures the soul. One photograph, of an artist called Philip, is particularly memorable, especially amongst the more famous names on the walls. And we could discuss all the famous names he’s shot over the years, but this image seems more him, in its humbleness, openness, heart, and soul. Dressed casually in a green baggy T-shirt and jeans, Philip is staring right into the camera, fiddling with his hands.

“It’s so fascinating about photography, isn’t it? That you can tell from a mile off who a picture is by,” Wolfgang laughs. Not that there’s a formula to the way he works, each portrait “has to be felt new each time.” And this portrait of Philip, for all its apparent simplicity, took years to shoot. “I had been observing and noticing him, and wanting to take a portrait of him for some years, so in my mind it matured. But because I was embarrassed, I could never ask him if he would sit for me. Then this picture was taken backstage at a Meadham Kirchhoff show at London Fashion Week, the most unlikely setting for such a personal portrait. It took me literally five minutes, but years as well. That’s the amazing thing about photography, it can condense years of thinking into a moment.”

Wolfgang is not one of those photographers taking pictures all the time. “I’m not walking around all day, every day, with a camera,” he says, standing in front of a portrait of an anonymous young man, dressed in purple robes, in front of a purple car in the Saudi Arabian city of Jeddah. There’s something sphinx-like and intriguing in the man’s expression and circumstance. “I have a strong sense of embarrassment, which means that only occasionally is there a clarity that overrides it, that means I can take the picture. In this moment, in the old town of Jeddah, when there was a lucidity. I was seeing everything with such clarity. I just felt I had to take these photographs.”

“I thought Saudi Arabia would be the worst place to ever go to as a gay person,” he continues. “Then, when you are there, you realize there are five million people living in Jeddah, and the people I met were, of course, nice human beings. Wherever I go that’s been my experience. People are people, as the Depeche Mode song goes. This whole demonization of the other doesn’t work when you are up close and face to face.” Which maybe stands as a nice closing mantra for the exhibition, for Wolfgang’s work, and his approach to photography. It’s all about finding the humanity and universal emotional center of us all, collapsing us and them together.

As I leave Wolfgang to his boxes of prints, wall plans, and hard-working assistants, he seems remarkably calm — but then he’s done this all before of course. Few people get two Tate retrospectives. Less get them while they’re still alive. So if he doesn’t seem particularly nervous, maybe it’s because he’s rightly confident in the power of his work, it’s there for all to see. Before leaving he points to a large, beautiful, abstract print. “A lot of people want to know what these works mean,” he says. “They want a manual to read it correctly, but it’s just about accepting and bearing what is in front of us. The irrationality and absurdity of life is so powerful that sometimes you have to embrace it.”

Read: From one icon to another, Arca is shot and interviewed by Wolfgang Tillmans.

Credits

Text Felix Petty

Photography Wolfgang Tillmans