When Kanye West wore a $43 Dickies workwear jacket to this year’s Met Gala, it signalled a shift for the American workwear manufacturer that began in 1922 and came to epitomise humble uniforms worn by working-class labourers. It also presented a paradox. One the one hand, workwear is fashionable, and is worn by plenty of people (Kanye included) who don’t really require it for their everyday life — least of all for their profession. On the other, it’s an anti-fashion uniform for many who do; people who wear it out of necessity, rather than as an accessory.

Workwear, after all, was once a cipher of social standing, quite literally distinguishing the socio-economic hierarchy between blue-collar and white-collar workers. It was practical and durable, made for comfort and utility: designed quite literally for physical work, to get dirty in and to be worn every day. In some ways, it is the antithesis of fashion, in that it emphasises collective anonymity over any expression of individuality. More than that, for so many people Chore coats, carpenter trousers, cotton overalls and utility vests aren’t just clothes; they are denominators of working-class life, a sartorial embodiment of a hard day’s work.

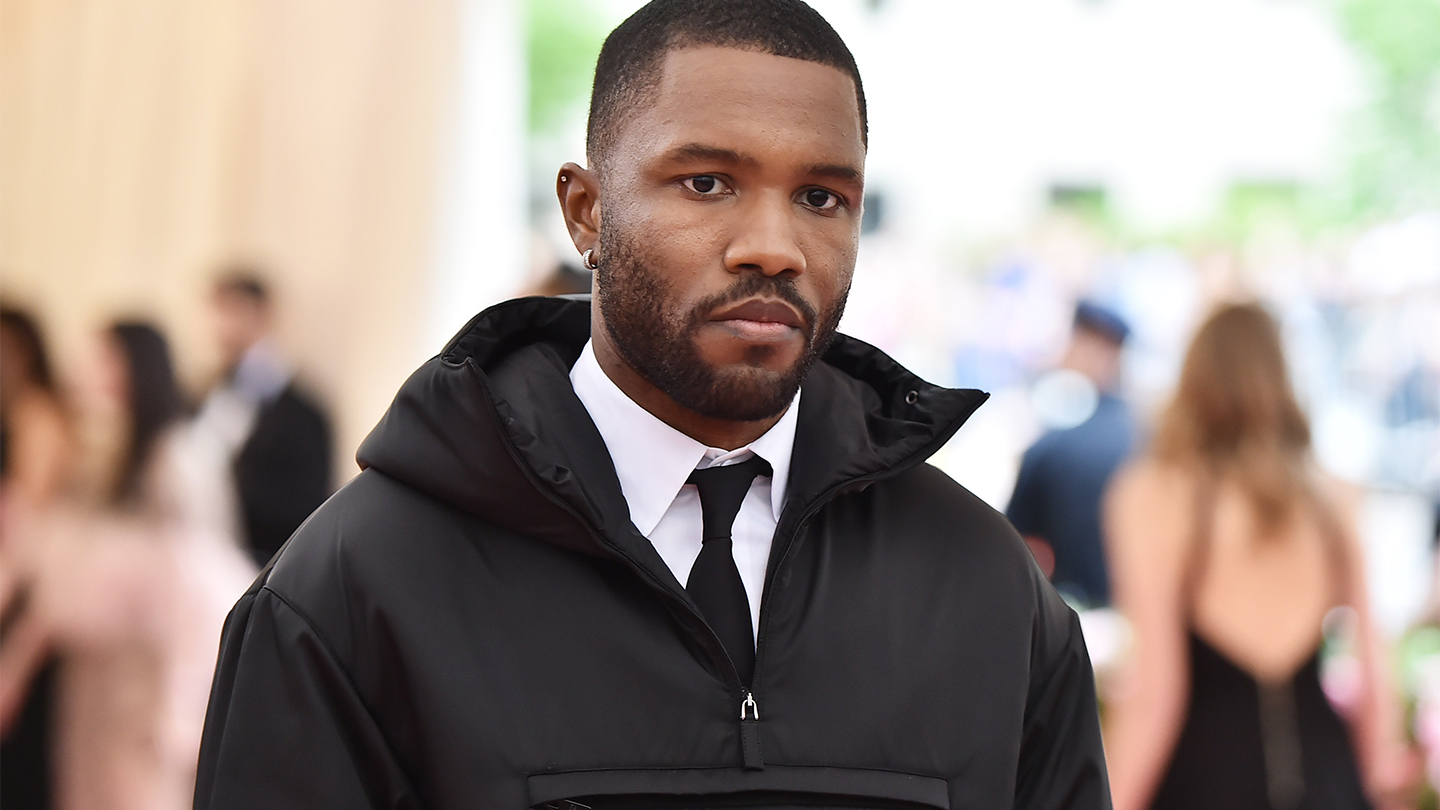

You would think within millennial professional life, there would hardly be a need for clothes like this. More people work remotely on their laptops than ever before, or in beanbag-strewn offices of tech start-ups and in jobs that didn’t exist five years ago (hello, influencers!). Yet fashion has co-opted plenty of workwear over the years. There have been clip-on ID badges at Prada, nurse’s uniforms at Louis Vuitton, Raf Simons’ high-vis firefighter jackets at Calvin Klein, Martin Margiela’s paint-splattered plimsolls and that Vetements DHL t-shirt. Yohji Yamamoto has been making luxe-workwear for decades, and Junya Watanabe pioneered collaborations with workwear giants including Dickies, Carhartt, Hervier and The North Face. More recently, Timothée Chalamet wore an oversized Off-White shirt that wouldn’t look out of place at a Midwestern gas station, and Frank Ocean resembled a dashing Boots security guard in a Prada nylon anorak over a white shirt and black tie at the Met Gala earlier this year.

Long before it hit the red carpet (although Tupac was an early trailblazer, wearing a marquee-proportioned denim workwear to the Soul Train Music Awards in 1993) workwear was a subcultural staple in the 80s and 90s, mixed-and-matched with military garb, skatewear, sportswear and thrift-shop finds. Back then, it was distinctly anti-fashion — but fast forward to 2019, and streetwear is the fashion industry’s favourite buzzword. Once-subcultural labels are veering further towards the mainstream, and as a result, there’s something about traditional workwear that maintains that anonymous, authentic sensibility which so many streetwear labels have lost as they’ve mutated into global brands.

So what does fashion’s obsession with these humble clothes say about the shifting symbolism of them? So far, it’s that luxury pundits love nothing more than playing dress-up in blue-collar uniforms. That can be problematic; some critics have labelled it as class appropriation. It turns out workwear may not be woke-wear.

But hold off on rage-tweeting for a second, and consider the fact that a generation of fashion designers are handling it with a sincere and very personal point of view. At London Fashion Week Men’s this past weekend, there were several designers — Craig Green, Kiko Kostadinov, Samuel Ross of A-COLD-WALL* — whose canon includes utilitarian workwear-esque clothes that are far from the black-and-yellow cliché. Theirs is an altogether more nuanced take on the workwear and uniforms that they grew up seeing their working-class families work in every day. It speaks to functionality, yes, but also of a romanticisation of the everyday hero; an exploration of clothes with cultural meaning — rather than just another feathered cape with millions of sequins.

Take Kiko Kostadinov, whose dad works in construction and mum as a cleaner. When he moved to London from Bulgaria as a teenager, Kiko would work part-time with his father on weekends and despite never seeing their work clothes as anything extraordinary, he began to explore it when studying at Central Saint Martins. His first collection was brimming with fuss-free navy cotton shirts, alongside weatherproof Ventile trousers with twisted pleats that cleverly concealed spacious pockets. He took his inspiration from the clothes he saw his parents in, combining it with references to Danish, Japanese and Swedish workwear catalogs, while turning it into something new, cleverly constructed and thoroughly modern. “It was a natural thing,” he explains. “When you reference something like that, you need to smash it and turn it into something new so it’s not so literal. Why would you want to buy it from Prada when you could buy it from Patagonia?”

Kiko’s show last Friday explored the uniforms of the horseracing world in three sections: the jockeys in colourful silks, the well-to-do equestrian patrons in tailoring, and the horse handlers in utilitarian hoods and panelled anoraks and shorts. It illustrated a microcosm of society, pointing out clothes is a signifier of social rank. “Three sets of uniforms, three different groups of people blending into one and divided at the same time,” as he put it.

Craig Green also grew up in suburban London, in a family of plumbers, carpenters and electricians. Like most British children, he went to school in a uniform, attempting to subvert it at any given chance, whether that was swapping his trousers with tracksuit bottoms, or replacing his school shoes with black sneakers. Nowadays, Craig makes a very modern kind of uniform — one that “romanticises old technologies” — in a lo-fi, adjustable-drawstring-tied kind of way. “I’ve always been fascinated with that idea of communal way of dressing and ways of grouping people together,” he once told me. “My [first] collection was about the relationship between workwear and religious wear, and how one was for function and one was for spiritual function, or an imagined function. They have such similarities between them in terms of their utilitarian, simple nature.”

Craig’s latest collection had brown cargo trousers with strapped external pockets, terracotta leather overalls spliced with knitwear, and his signature panelled work jackets in quilted pink silk, grey nylon, cobalt cotton and tarpaulin-like marigold. It was workwear re-worked into something beautiful, special and individual. It spoke to something banal and mundane, but also to something extraordinary — with disparate references to apotropaic mirrors, Erastian anatomical drawings, shirt-folding utensils, Egyptian funeral rituals and celebratory Mexican Easter flags.

His exploration of workwear is especially pertinent as industrial jobs are becoming increasingly mechanised. For him, functional clothes designed for physical labour is romantic — and perhaps quaint — in a world of drone-delivered packages and zero-hour contracts in Amazon pick’n’pack warehouses. Rust Belt America, with its abandoned factories, and northern England’s deserted mines, are certainly not thriving with the employment that would have instilled in uniforms and workwear a sense of collective identity. It’s only natural that those garments have transformed into a symbol of something that once was, a distant memory of simpler times, a relic of a more deferential past.

A couple of years ago, designer Heron Preston collaborated with New York’s Sanitation Department (DSNY) for a collection that riffed on the uniforms of its workers. Without an ounce of irony, he told me at the time that “people who use their hands, people who sweat, people who do hard work is kind of like one of the most honest ways of working, and that’s my point of view.” Since then, he’s also collaborated with NASA (yes, as in the astronauts) and Carhartt, remixing the utilitarian garments with a sustainable bent. His debut show in January, held in Paris, explored the notion of security guards and Transportation Security Administration agents (customs officials) with plenty of padded utility vests and pocketed shirt-jackets. In many ways, he is toying with the tropes of Americana and transfiguring them into urbane clothes for a generation of like-minded people: creatives, DJs, graphic designers. In his case, it feels organic, and indicative of a sartorial interest in the people he encounters on the street — rather than just people in streetwear.

So, workwear is now firmly on the fashion agenda. But for all the spectacular reimagining of it by talented designers, the best thing about it remains resolutely anti-fashion. You can only get your hands on the real thing by working for it.