When you walk around Budapest you are immediately aware of the overlapping political eras that have formed the city, like many others in the region that fell behind the iron curtain. Dusty fashion shops consisting of polyester skirt suits on chipped and greying hand-painted mannequins share streets with new ‘Candy Stores’ filled with the vast array of sweet brands imported from America.

The current environment of this place is not, however, so easily explained as simply ‘before’ and ‘after’ communism. The current government, led by Viktor Orbán, has many Hungarians worried and protesting due to the mix of right-wing ideology and communist-style control, the later specifically exemplified in a worrying change to the Hungarian constitution in 2013.

What has this meant for art? Many of the major museums are now run by government approved directors and curators, turning institutions such as the Ludwig Museum from coherent spaces tracing the semi-underground histories of art in the region, to spaces with jumbled programmes that are often described as ‘populist’ and ‘apolitical’. The irony being that when an institution is ‘apolitical’ it still pushes an implicit politics and demonstrates just how divisive culture is within society. Refusal to engage with politics is, in itself, a political statement, especially when living in such a politicised state.

In this vein, and as a productive counter perhaps, many ex-curators from the Ludwig, as well as other artists and curators, have set up the Off Biennále – the first of its kind, taking place across the city between April 24th and May 31st. For this first iteration of it, everyone involved is giving their time to the project, in the most charitable/DIY sense of the word. The curatorial team – Nikolett Eross, Anna Juhász, Hajnalka Somogyi, Tijana Stepanovic, Borbála Szalai, Katalin Székely and János Szoboszlai are supported by players from across Budapest’s art scene – to make up fundraising, press, and international teams. The main thread that is stitched through the Off Biennále’s programme (and hinted at in the name) is that none of this has state funding, and all of the spaces involved are also not funded by the state. This has created a mixture of project spaces, temporary locations, and even some commercial galleries, forming an eclectic mass of places in which to see the art managing to flourish outside of state-sanctioned bastions of culture.

It is truly astounding that in its first year there are nearly 80 venues included, curators have described the positive effect of working together, in what they see as almost a federation, or a collective institution that is Off from the institution itself.

Highlights of the Biennále include a new not for profit gallery 115-106, who are showing artist duo Laci&Balazs, and a group exhibition subjectively reflecting on the theme of migration, titled Horizontal Standing,and produced by curator-artist couple Katalin Simon and Zsolt Vásárhelyi, in the apartment Simon abandoned when they left for Berlin two years ago. Galleries Knoll, Telep and Centrális are all showing accomplished group exhibitions, and Neon gallery will be presenting work and a talk by Marina Abramovic’s former partner Ulay.

One of the coolest young galleries in Budapest is Supermarket gallery, showing work by Ovidiu Anton, Lprinc Borsos, Anna Witt and Hannes Zebedin. Three of the artists live in Vienna, and the fictive contemporary artist Lorinc Borsos (born in 2008) works in Budapest – the international edge to this exhibition is evinced in the theme of the exhibition: “which forces in society work on which visions of coexistence”. Zebedin’s installation What’s Happening In Tottenham? uses burnt carpet, referencing 2011’s London riots, with neat espresso cups and a video of Molotov-style candles burning in various sites along Tottenham High Road. Anton’s anarchy symbols, collected in photographs and then remade through tight biro scribbles, draws on the general feeling in the show, of European discontent in a post Financial Crash world, but also reminds us of the potency of the Biennále in its silence (not acting directly against government, but simply outside), as the bare areas of paper that have not been attacked with the pen, are the areas that reveal the symbol itself and are the most loud.

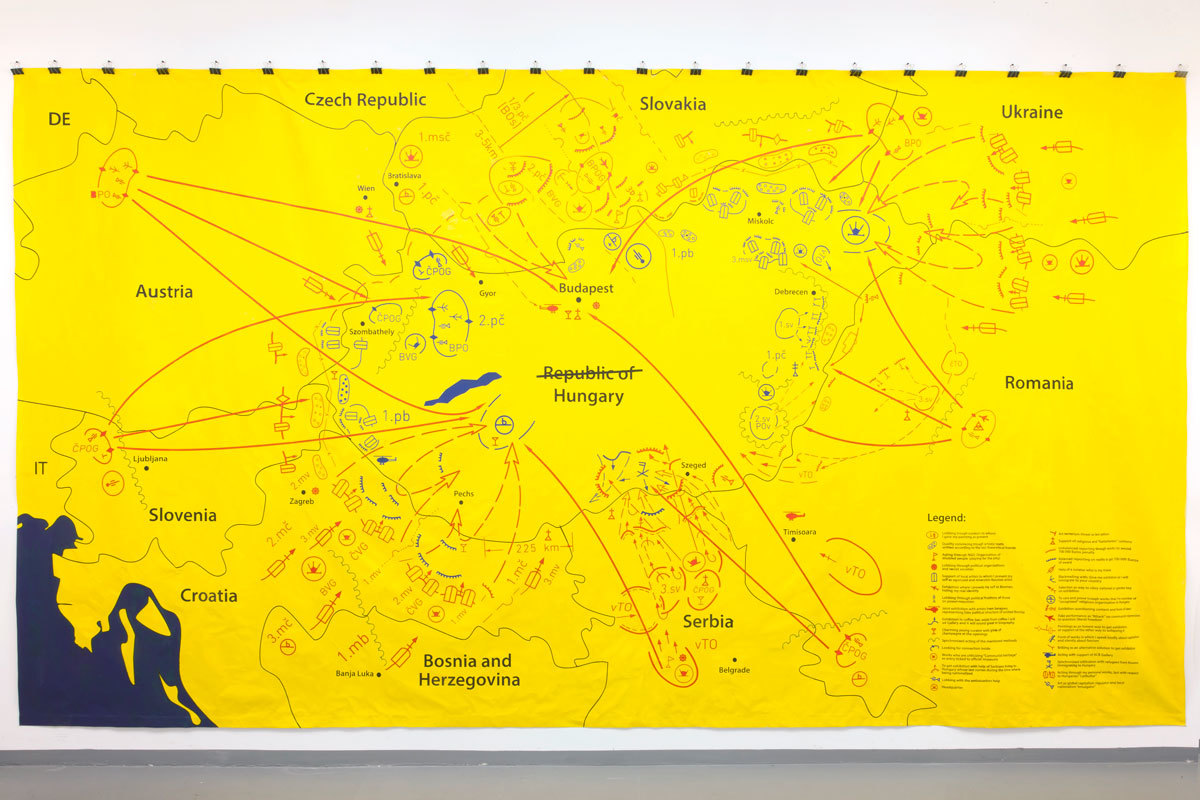

Notable solo projects include Eva Kotátková at Kisterem Gallery and Mladen Miljanović’s (Bosnia and Herzegovina’s representative at the 2013 Venice Biennale) Operation Hungary at acb attachment, which is a hand painted map of his attack on the art world rendered in the style of army plans and particularly remarking on how we view the region from the West, with symbols on the map to signify: playing up to a Bosnian identity, buying young curators champagne and threatening to emigrate to your country if not given a show.

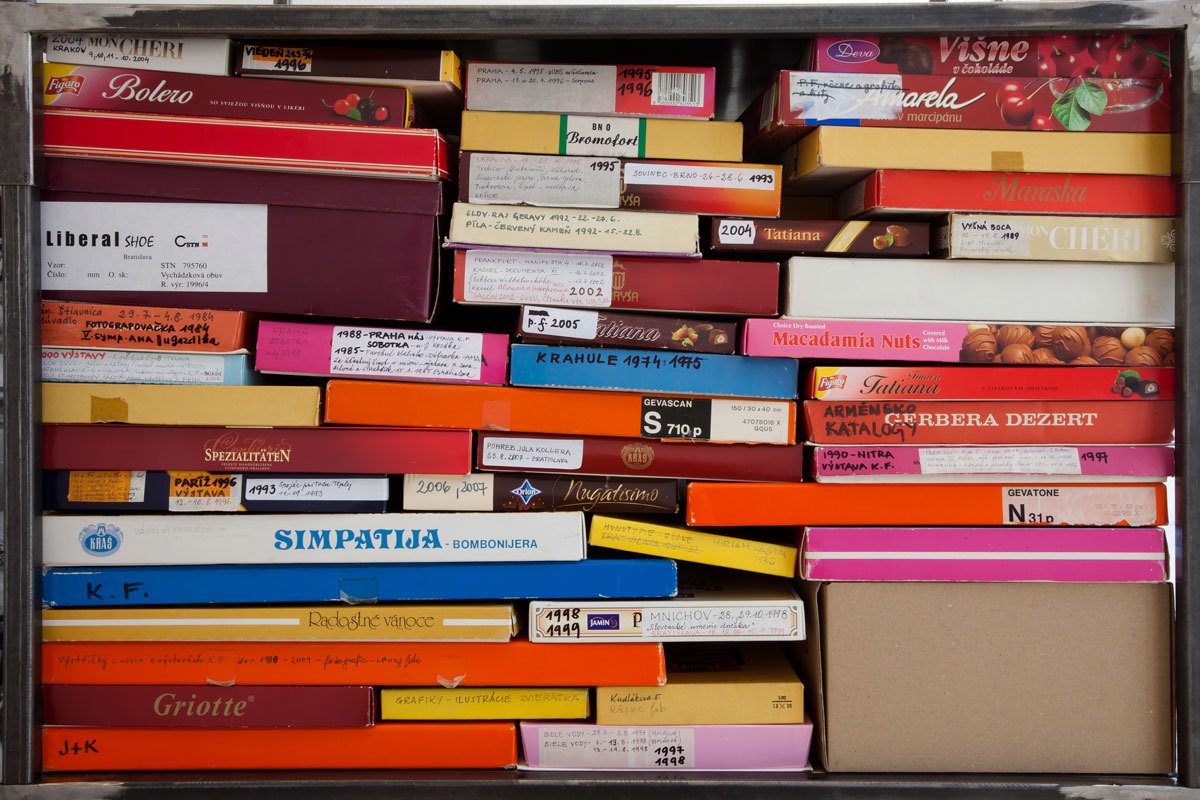

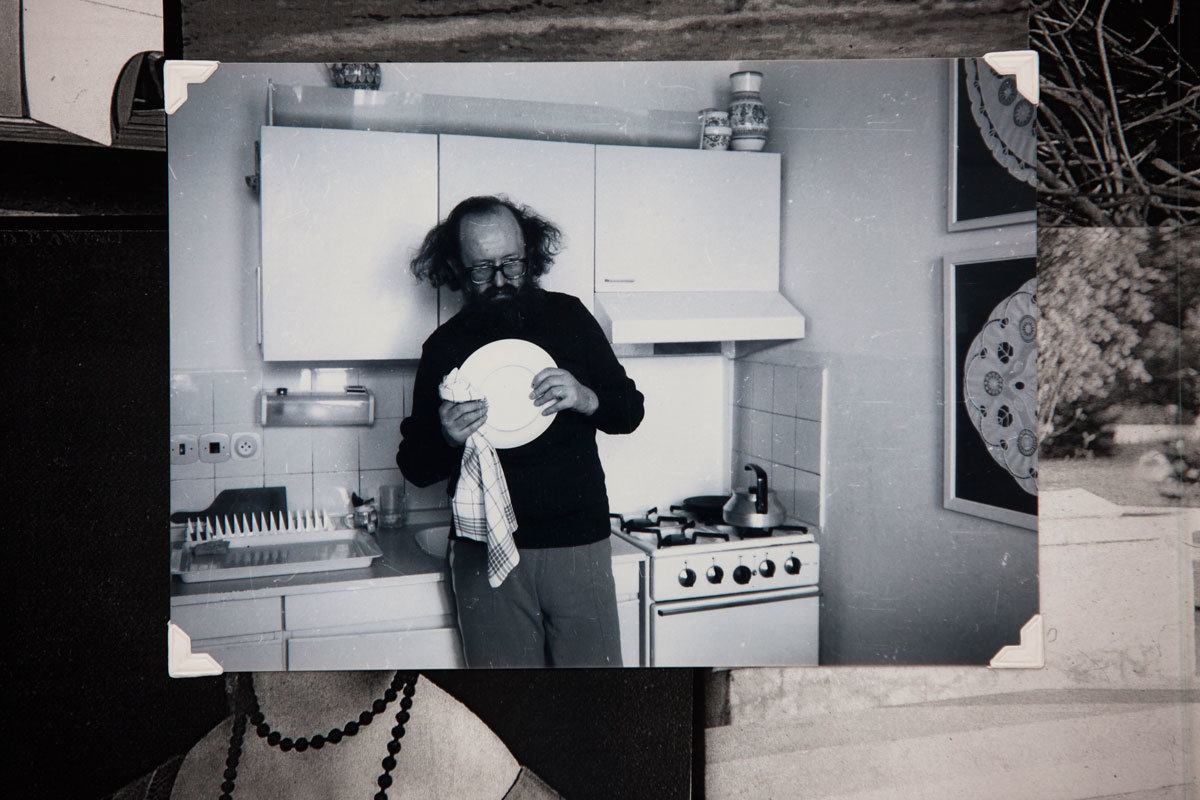

The star of Hungarian art, Dóra Maurer (who recently had a solo exhibition at Kostyál in London) has a small solo exhibition at Vintage Gallery, and is also part of the impressive Bookmarks show – a collaboration between Vintage, acb and Kisterem. Bookmarks is housed in a former leather factory, turned private museum, turned redundant space in the wake of the recent financial crisis, and is located outside of the city centre. The title, Bookmarks, alludes to the fact that organisers see the exhibition as moments from, rather than an overview of, the last few decades of Hungarian contemporary art – in particular the Hungarian neo-avant garde art that flourished between the 60s and 80s, and the post-conceptual art which took influence from them, and was made by younger artists emerging after the fall of communism in 89.

What is important with this show is the context of Hungary after the 1956 uprising – where exhibiting work that did not depict ‘reality’ (or fall into the state approved style of social realism), that is, abstract art, was prohibited. Works by Dóra Maurer, as well as Imre Bak and István Nádler, became trangressive in their conceptual rationality. And you can see the influence their work continues to have on a younger generation of artists such as Little Warsaw, Ádám Kokesch and Tamás Kaszás, which is one of the core feats of the Bookmarks show. It demonstrates a stuttered, as opposed to linear, landscape and timeline of Hungarian art, one that is at the mercy of those in power, yet often recuperated or nourished by other artists and supporters themselves. Political tension resulting in creative repression and expression has existed in Hungary for a while, as it did in many other Eastern Bloc countries.

The tension around, and community recuperation of, visual art, is what the Off Biennále reiterates. Where Bak and others produced Budapest’s first abstract art exhibition in a completely DIY fashion (that was swiftly shut down by the communist authorities at the time), the Off Biennále too is in existence through the hard work of those working outside of the state. The Biennále is not ‘Off’ in a negative way – it is not in opposition to, but rather it is a productive Other.

Credits

Text Rózsa Farkas

Images courtesy The Orbital Strangers Projet and OFF-Biennale Budapest Archive