In October of last year, we invited a series of young writers to reflect on what Britishness means to them for The Superstar Issue of i-D. From the nostalgia of home, to fears over rising rents, to the sense of displacement from the place we thought we once knew, our identity has never been more complex. So what does being British mean for a country facing its biggest shift in decades? And does it still matter? Read the full series here.

It often feels like it’s not possible to say what Britain is today, only to remember what it has been. This is because usually, Britain doesn’t seem like a tiny island floating in the North Atlantic as much as it does a ridiculous argument that has been going on for centuries, constantly recalibrating our ideas about who we are and what we should be doing with our lives, which trousers we should wear and whose wisdom we should listen to, where we should drink, how we should defend ourselves and for whom we should reserve our love and loathing. Britain is a ridiculous argument that has been fought at various points in history by gentrifiers and locals, Catholics and Protestants, pub bullies and Pubwatch, Netto and Safeway, grungers and townies, Jeff Bezos and the high street, logic and daytime fireworks, cops and black bloc, Blur and Oasis, mad cows and fire, Keane and Vieira, storm clouds and cricket, farmers and crop circles, ecstasy and Section 63, the iPhone and the attention span, tarmac and the Green Belt, traffic and the rain, Friday night and Saturday morning.

Your British identity, the coordinates that your life has progressed along, has been defined by this endless succession of squabbles, character-building tiffs that push you in and out of love, find you friends, toy with your self-esteem, buy you new trousers. Fighting helps us figure out who we are. The problem is the sense that Britain is loud and arguing barely leaves us these days, for all the usual, clichéd reasons that have become clichés precisely because they’re only getting more true – we have too many screens and not enough money, the former making us profoundly aware of the latter. Brexit is an argument that feeds like a happy leech off of screens and poverty, such a huge and ubiquitous argument now that it’s hard not to recoil from the word itself, harder still to believe there’s anyone left in Britain with the authority or nous to actually settle it. Rather than enrich the life experience of anyone living here, all it seems to have done is make Britain groundbreakingly stupid, petty and divided.

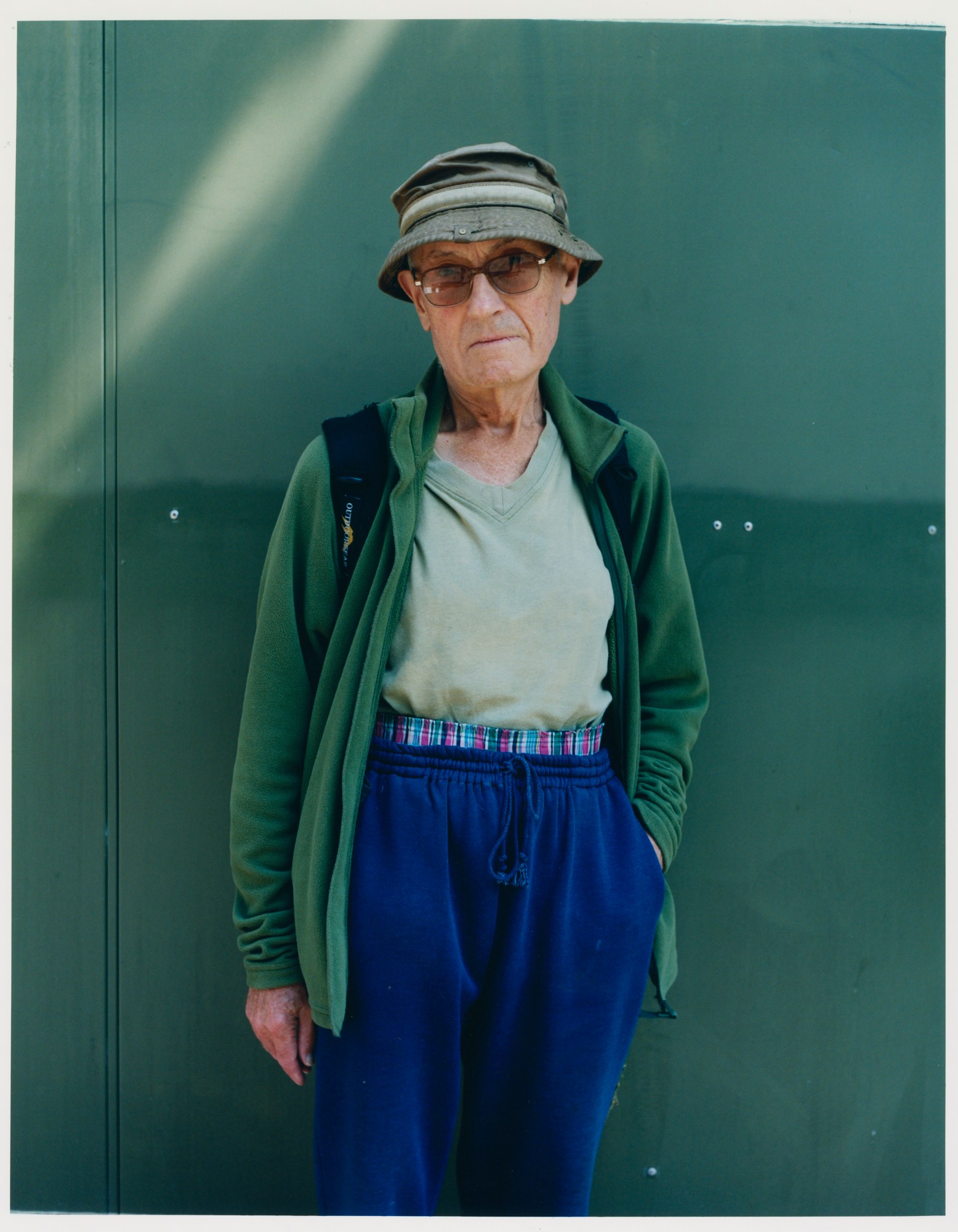

Take the man in the street. He used to seem like a decent sort of chap, someone you’d meet in the queue for the barbers or down the pub and be able to have a lively but good-natured chat with about the state of the modern world. Now, as the internet functions as a digital fight club training everyone in the art of not backing down, it can be difficult to hold on to the notion that the man in the street isn’t a cat-calling, dog-whistling data-bigot, gleefully drowning in his own cruel rhetoric. And so people retreat back into their online echo chambers, their warren-like support networks of friends and family, their views becoming more unchallenged and more entrenched, rendering Britain a set of distant hills crowded with people waiting to die on them. In the age of Twitter, everyone is a newsreader, and the news always seems to be awful.

There has to be something more than this. Increasingly, it feels as though the internet and happiness simply aren’t compatible – you wonder if a human’s ever been born with the requisite serotonin to handle the amount of misery it can bring into your life, with its drip, drip, drip of Remain vs Leave, Trump memes, woke outrages, face tattoos, Instagram envy shots, football stream schadenfreude, planetary collapse photos and terrifying, backflipping dog-robots that someone, somewhere seems to think will improve the world. Britain isn’t the internet – not yet – but for most people born after 1990 being online is a near-permanent state, and to shoulder that amount of data poisoning and dread fatigue as a generation is exhausting.

Perhaps through the merciful drive of some internal motor of self-preservation, I’ve realised that I’ve started to seek out those parts of Britain and life on this island that can’t be argued with, the rare constants that have always been humming away apathetically in the background as tempers have flared and the digital has continued its invasion into the real. I find myself staring for prolonged periods at the sight of the wind lifting and dropping the leaves of the trees, an interaction between different natural elements totally untouched by man or machine; enjoying the sound of the irrepressible British rain hammering upon the roof of a parked-up car. I resist the urge to check my phone for the first hour of each day, listening instead to the dawn birds and trying to learn their respective calls. Most of all, I think about the lilac buddleia lining the rails to my hometown, and the way their seeds have gradually spread in the slipstream of commuter trains along the entire route, turning it into a purple gateway to a world I used to know, a world that I thought would be preserved in amber forever but that is changing, constantly and imperceptibly, behind my back.

Credits

Photography Sam Rock