Selin, the hero of Elif Batuman’s new book, The Idiot, was brought up by Turkish parents in New Jersey and went on to study literature at Harvard in the 90s; all of which is also true of Elif Batuman, 39, the author. Batuman is an established non-fiction writer but this is her novelistic debut, and at heart it is a book about nothing. Selin, by her own account, doesn’t really learn anything concrete about language over the course of the freshman year described in these pages, nor does she have much to teach anyone; she has a go at teaching in the English as a Second Language (ESL) programme but her student, Joaquín, goes blind after three lessons. So the book is about nothing. It’s a sexless love story without love and a life story without any lessons.

It’s also a book in which the hero and the author are to all extents and purposes the same person (they are both the idiot of the title) and this makes it an example of autofiction; meaning the novel is a loosely fictionalised passage of autobiography, usually told from the first person. Autofiction is surely the most popular genre of literary novel at the moment, as demonstrated by the success of titles such as Teju Cole’s Open City (2011), Ben Lerner’s Leaving the Atocha Station (2011), Tao Lin’s Taipei (2013) and Rachel Cusk’s Outline (2014), and also one that mirrors changing attitudes towards authenticity.

Speaking five years ago in an interview, Batuman was asked to comment on the phenomenon of publishers requesting memoirs rather than novels. This sometimes happened, she suggested, because those publishers wanted things to be true, “And it’s actually an odd thing to want. The rationale is that people these days are no longer interested in novels, because we live in a newsy age, we care about facts, we care about the truth.” As we’ve seen lately, this is no longer the case. But Batuman doesn’t think it was ever really the case and believes instead that we enjoy stories for what they can tell us about the world and how it works, or doesn’t. In this sense, autofiction is an ideal form for a post-facts age: it reflects a moment in which we all tell our own, carefully edited, largely dishonest stories about ourselves online; and in which the personal essay is one of the dominant forms of journalism.

Batuman’s first book The Possessed (2010) was a collection of essays about her love of Russian literature. Selin loves Russian literature as well and at Harvard she falls in with an Eastern European crowd, making friends with a Serbian girl called Svetlana and falling in love, from a distance, with a tall Hungarian mathematics student named Ivan. Because of its setting, the story is also entwined with the modern tradition of great American East Coast college novels such as Bret Easton Ellis’s Rules of Attraction (1987), which was set at a liberal arts college in New Hampshire, Donna Tartt’s The Secret History (1992), set at a liberal arts college in Vermont, or Jeffrey Eugenides’ The Marriage Plot (2011), set at Brown, Rhode Island. Like those books it offers a warm slice of coastal elitist escapism and nostalgia, in this case for the 90s. It’s a coming-of-age autofiction: an autobildungsroman.

Autofiction is an ideal form for a post-facts age: it reflects a moment in which we all tell our own, carefully edited, largely dishonest stories about ourselves online; and in which the personal essay is one of the dominant forms of journalism.

The story comes from a 300,000-word draft Batuman wrote at the turn of the century when her college days were still fresh in her mind, forgot about, and then found again in the cloud while she was writing a different first novel. Before long she had floated that project away into the cloud and was working on this forgotten one instead. It’s like finding an old, embarrassing diary and, rather than burning it, publishing it internationally. The result is a book that dwells on the existential confusion of youth, and it begins with a quote from Marcel Proust, from the second volume of In Search of Lost Time (1913-27), praising the spontaneity of those awkward years and claiming, “adolescence is the only period in which we learn anything.”

Selin and Ivan, her love interest, often struggle to hold a conversation in person so they mostly communicate by college email. Their messages are long, like letters, and strange and intense, and often left unanswered for long days of ghosting. But she likes this new way of speaking because it allows her to spend ages crafting herself on the page. It’s another form of rewriting: as the author can rewrite herself into a novel, so Selin can rewrite herself into an email correspondence. She also likes that she can spend ages reading and analysing Ivan’s sentences, which is essentially what she came to college to do: textual analysis. Together, she thinks, their letters form a twisting narrative of their own, as “each message contained the one that had come before, so your own words came back to you—all the words you threw out, they came back. It was like the story of your relations with others.”

This was at the dawn of the information age. Selin thinks that email, the first form of popular communication in which such a shared record was kept, is great. Ivan, who is something of a downer, thinks that it is very detached: “you wrote something, and I wrote something else, and then you wrote something else. It was never really a conversation.” Even these halcyon days of online flirtation—all longwinded philosophical showboating and no pictures of dicks, unfolding a full decade before Mark Zuckerberg would drop out of his own studies at Harvard—were marred by a certain disconnect. Selin’s child and adolescent psychologist, whose desk is decorated with toy pigs, doesn’t like the sound of her email correspondence with Ivan, and says it makes him think of the Unabomber (a terrorist, mathematical prodigy and Harvard Graduate who orchestrated a nationwide mail-bombing campaign against figures associated with modern technology). She asks him why. “I don’t know,” he says, “I just keep thinking about the Unabomber.”

Later he elaborates that it’s something to do with the power of computers, and the idea of a person hiding behind their words: “thanks to this e-mail, you can have a completely idealized relationship. You risk nothing. … Now, here’s something I’d like you to think about. You don’t actually know a thing about this fellow, do you? It’s possible he doesn’t even exist.” But she’s fairly sure that Ivan exists because he’s in her class.

Everything that happens is treated with a refreshing, deadpan levity. At one point Selin goes to Paris with some friends: “When asked about her plans, Emery had simply said, in a contemplative tone, ‘I’m going to be walking some dogs.’ Svetlana had asked what kind of dogs. Emery replied, ‘I don’t know—just some doogs.'”

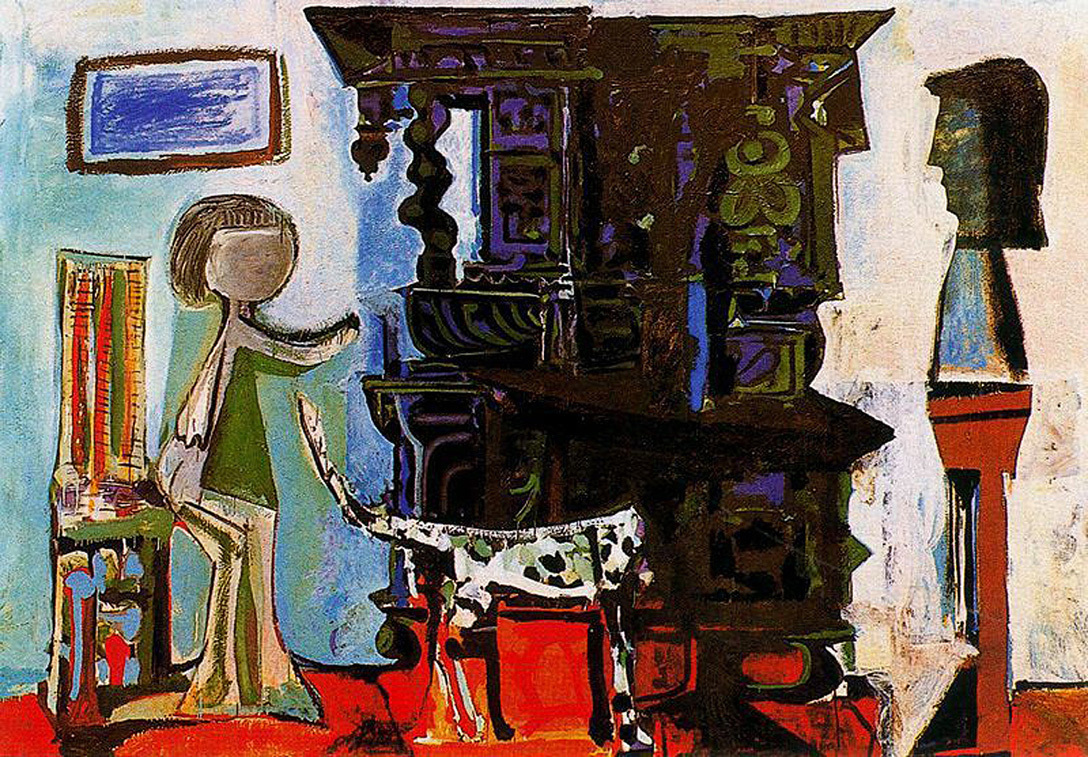

Afterwards, when she’s spending the summer teaching English in Hungary, one of her students makes an observation about Picasso, whose museum Selin had visited in Paris: “In class we worked on the conditional tense. ‘If I were Picasso,’ said Katalin, ‘I would love many women.’ A more beautiful girl wouldn’t have said that, I thought. Beautiful people lived in a different world, had different relations with people. From the beginning they were raised for love.”

Characters come and go like guests in a sitcom, popping up only to illustrate the absurdity of everything. In Batuman’s telling the world is absurd, but happily so, and everyone is an idiot one way or another, and nothing is neatly tied up at the conclusion.

When Selin is asked which figure from a painting she most identifies with, out of every painting ever made, she thinks about Picasso and identifies with the monstrous, unruly black sideboard in his Buffet de Vauvenargues (1959). Jokes like this, which are hardly even jokes, are what carry us through this narrative, which is hardly even a narrative; they are landed on and hopped off like lily pads in time. Characters come and go like guests in a sitcom, popping up only to illustrate the absurdity of everything. In Batuman’s telling the world is absurd, but happily so, and everyone is an idiot one way or another, and nothing is neatly tied up at the conclusion.

So the story concludes, more or less, with the introduction of a new character on the penultimate page: a small child named Alp who is living in an empty hotel on an unfinished golf course in a dismal snake-infested swamp in Antalya Province, Turkey—and really doesn’t have anything to do with anything—and decides to give Selin and her mother a tour of the uncertain grounds on a golf buggy, culminating in my favourite joke of the whole book. Although it’s not really a joke, so much as very funny and uplifting writing condensed into three perfect punchlines.

The Idiot is published by Jonathan Cape on 1 June

Credits

Text Dean Kissick

Images Pablo Picasso, Buffet de Vauvenargues