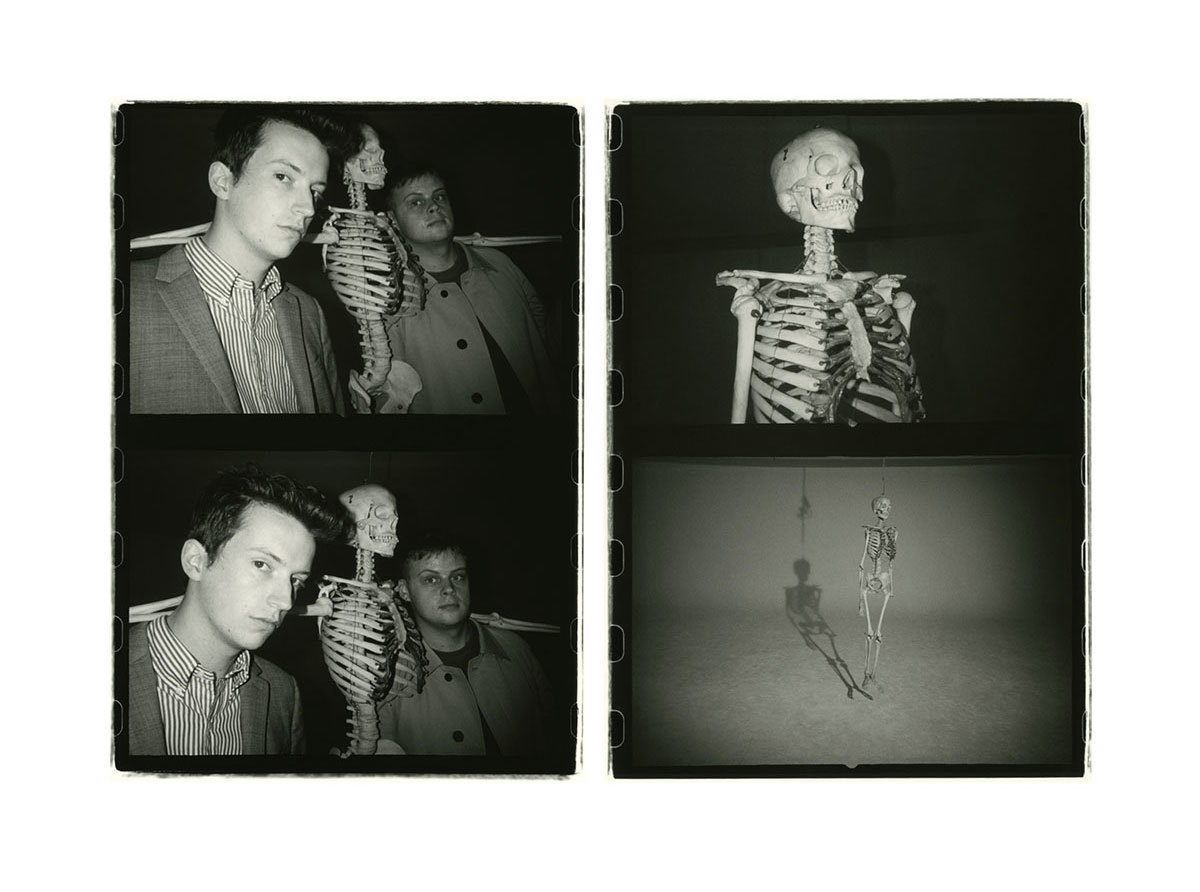

We’ve written about how excellent The Rhythm Method are so many times now that we don’t even know where to begin. South London boys with the sharpest pop nouses (sic) in the game, Messers Joseph Bradbury and Rowan Martin are the latest in a long line of storytellers from the city — pretty handy when you’re sitting down for a bit of a natter. Half Pet Shop Boys, half Chas and Dave, to listen to The Method — as we affectionately call them — is to listen to all the cars, bars, laughter, and fights of the capital (and still feel as though they’ve got a couple of tales up their sleeves). Put simply, when a man is tired of The Rhythm Method, he is tired of life. They’re going to the toppermost of the poppermost, Johnny, and they’re taking you with them.

Name: Joseph Bradbury, Rowan Martin

Age: 27, 26

From: J: Putney in South West London. R: Originally from Twickenham and now I live in a place called Hornsey in North London.

How would you describe what you do?

J: Musically it’s pop music, basically. We thought… Well, we haven’t thought long and hard about it, to be honest.

R: We thought about it.

J: Yeah, we thought about it briefly. And we get asked it a lot and the easiest way to describe it is pop music. It’s verse, chorus, verse, chorus. It’s around three minutes long. And it’s attempting to be catchy. So it’s pop music.

R: Kind of from the old tradition of lyrical, British pop music. Which we think is a great tradition. Pulp, Squeeze, Prefab Sprout, Madness. All these bands, going back to the Kinks. We want to take that lineage, rather than hark back to anything. We want to use that lineage now, in the same way that they did then.

What’s the best and worst thing about where you’re from in London?

R: One is that it’s very hard to get back to. It’s got very hard connections. Which, in a way, was a bit of a blessing for us because we spent a lot of time with each other on first trains and last trains and also night buses and long fucking walks as well.

J: We’ve walked back from central London a few times.

R: So it has that going for it, I suppose.

Who’s your favorite Londoner?

J: Suggs.

R: Michael Caine. I’ve read Michael Caine’s book, The Elephant to Hollywood. At the back of it there’s a list of his favorite dance albums and then his recipe list.

J: Have you listened to his Desert Island Discs? He actually makes chill-out music.

R: Yeah, he’s really into chill-out. Does a bit of spoken word on some of it.

J: He’s never released it, I don’t think, but I’d love to hear it. Unfortunately he’s a Tory.

If your life was a short story, what would be the key points that have got you to where you are today?

J: Meeting when we were 16/17 outside Nambucca on Holloway road, which was described by the NME at the time as “North London’s Indie Mecca.” Everyone was in bands back then, which was great because we had a place to go every Friday night. I mean, the majority of it was shit, including our own bands. Rowan’s was better than mine. Fundamentally he’s always been a good songwriter, it was just the presentation that was a bit off.

R: It was a flamboyant era.

J: And then the next stage would be, I guess we grew up together from that point onwards.

R: We lived together.

J: Yeah, that was the main start. But the band, I guess, started just me when I was going through a particularly bad time. An extended period of unemployment and smoking a lot of the old ‘erb and eating a lot of Subway sandwiches. Just purely out of boredom.

R: Such a great time! Not for you, just to talk about.

J: It was 18 stone, I got to. It was really my Gary Barlow, my Brian Wilson period.

R: You were in the sand box?

J: Yeah. Gary Barlow in the sand box. So, yeah, out of boredom, I was just mucking around on my mom’s iPad on Garageband and somehow managed to get the hang of that, almost. And then started putting words that I’ve always been writing to it. And then a year later we moved in with each other and that’s where it all sort of began properly.

What do you want to say with your music?

J: It was never really thought out. It was actually accidental almost. The first song we wrote was “Home Sweet Home” and we were trying to come up with the chorus and we just literally had that lightbulb, yeah, we need to make this a London centric song, kind of thing. So, can’t really do much better than literally saying “London” over and over again. And then we kind of discovered that, I mean, naturally the way that I write lyrics and he writes lyrics and songs, it’s very London influenced anyway. So that it the main aim really, to be about where we’re from. A sort of “say what you see,” kind of thing.

What role do you feel you play within the UK music scene?

R: We kind of want to do what we feel isn’t being done by our contemporaries. There is good music being made, but it’s quite a narrow field. There’s a certain type of sound. So we kind of want to resurrect some old sounds and invent some new ones. Bring back personality to music is our main thing. There’s good songs out there but you currently don’t know who sings them.

J: The in-thing is to be political now. And there’s plenty of so called political bands and a lot of them say, like, “No one’s saying anything nowadays” which is just bullshit because it is, as I say, the ‘in’ thing. But it feels like a lot of these political bands — I won’t name them because I’m not interested in trying to cause beefs or whatever, that’s bollocks — it’s a very easy kind of politics. I dunno. Retweeting Jeremy Corbyn doesn’t really make you a political force. Our kind of political songwriting is very much personal. Our politics is in our personal lives kind of thing. It’s not, like, wearing a beret and putting your fist in the air and talking about Marxism and shit. It’s just talking about everyday life. I think that’s how you be political really.

R: It’s much more political to talk about the mundane. We always think in terms of the small screen rather than some sort of gigantic big screen revolution. It becomes self-aggrandizing. And we always want to avoid that.

What are thoughts on the UK post-Brexit?

J: It’s exactly the same as it was really, isn’t it? Obviously on a grander scale, the worst thing was, I guess, racist and xenophobic attitudes have almost been legitimized and a lot of people probably feel as though they’re allowed to speak like that now. Which is obscene really. But, in general, life’s exactly the same really, isn’t it? I mean, I’m pretty certain it’s not even going to happen to be honest.

R: Nobody’s really up for it, by the looks of things. I always thought, one of the strong points of this country was its mildness. Our cultural ecosystem depends on quite mild waters. And I feel like that balance has been upset now. Maybe for a long period of time. And it’s going to become harder for things to flourish in the way that they did.

What’s the biggest issues facing you and your friends right now?

R: Definitely rent. Rent prices. Everyone I know has no money. Even the people who are doing alright. And I’ll go beyond that and say it’s basically the bonanza that like people in business or people in power are having. And the fact that they can basically do what they want. And who’s going to stop them? Everyone’s suffering as a result of that. And rent is just one of the examples.

How do you feel about the future?

R: The most optimistic that I can be is that people are caring more. They’re more engaged. And you might get some really good art out of that. But the thing that depresses me goes to that eco-system thing. I feel like we’ve positioned ourselves a little bit. And the places from which natural culture can emerge from are going away as well. So I’m a little bit gloomy about London’s future. I think you’re going to start seeing a lot of people moving to other cities now. But that might not be a bad thing. You might get these amazing little renaissances happening.

Biggest achievement of 2016?

J: Two solids singles, that we’re very proud of.

R: Getting the Elton John play.

J: Yeah, getting our debut single on his radio show. I mean, just having him say our names and say he loves it was just incredible. That’s literally something to tell the grandkids, kind of thing.

What are personal and professional goals hopes for 2017? And then after that, in five or 10 years?

R: We’re thinking in terms of an album. I know the album’s kind of a redundant concept, maybe in its form that people buy it, but we’re thinking in terms of a body of work and a story. And every song we write seems to add another chapter to that. It doesn’t matter how it comes out, but we want to have it out there.

J: I feel we’re very close to that. A few songs away.

What film would your music best soundtrack?

R: We always think cinematically. We love film soundtracks and stuff like that. It almost has like a musical element. A West Side Story sort of vibe to it.

J: It is basically a concept album but not in an overtly pretentious way. It’s a concept album in the way that it’s just about real life and it’s about our life. We’ve basically been experimenting with the songs that we have and putting them in an order and it does feel like a start, middle, and end. It just has a few gaps to fill at the moment.

Who would you most like to work with, from any discipline?

J: Timothy Spall. He’d be a great character in a video. A song that we have called Wandsworth Plane, he’d be the ideal character. It’s a song about marriage and divorce. It’s almost like a telling of the future. So he’d be a great character.

Did you both always want to be musicians?

R: I’ve always done it. I’ve written songs since I was 11. I basically started writing songs as soon as I could play songs, because I was never really into cover versions. I still don’t really like them. I didn’t think that I would do it professionally, but I would always do it in some respect.

J: I’ve always been an attention seeker, show off kind of thing so I always wanted to be an entertainer of some sorts. I mean, I remember one year, I think it was 2012, my aim was to become a published poet. And I did it within like a week of the New Year which was pretty cool. But then I was, like, oh, I’ve done it now. And I realized you can’t really make a career out of being a poet. It’s like a romantic idea in your head. Then I realized Philip Larkin was, like, a librarian. All the best poets had jobs and stuff. I wanted to find a route so that I didn’t have to do a proper job. And being in a band is still the best was to do that.

Who are you tipping for 2017?

R: M. T. Hadley. He’s a good friend of ours.

J: And… I dunno. I don’t really engage with new music really. Ourselves!

Who, what and where influences your creativity?

J: London.

R: Ourselves.

J: And depression. Social media-induced loneliness.

Meet the rest of i-D’s music class of 2017.

Credits

Text Matthew Whitehouse

Photography Hanna Moon

Styling Max Clark

Hair Maarit Niemala at Bryant Artists using Moroccan Oil

Make-up Athena Paginton at Bryant Artists using Kryolan

Set design Mariska Lowri

Photography assistance Alessandro Tranchini, Ilenia Arosio

Styling assistance Bojana Kozarevic

Hair assistance Benjamin David, Mikaela Knopps

Make-up assistance Billie McKenzie