This article originally appeared on i-D Germany.

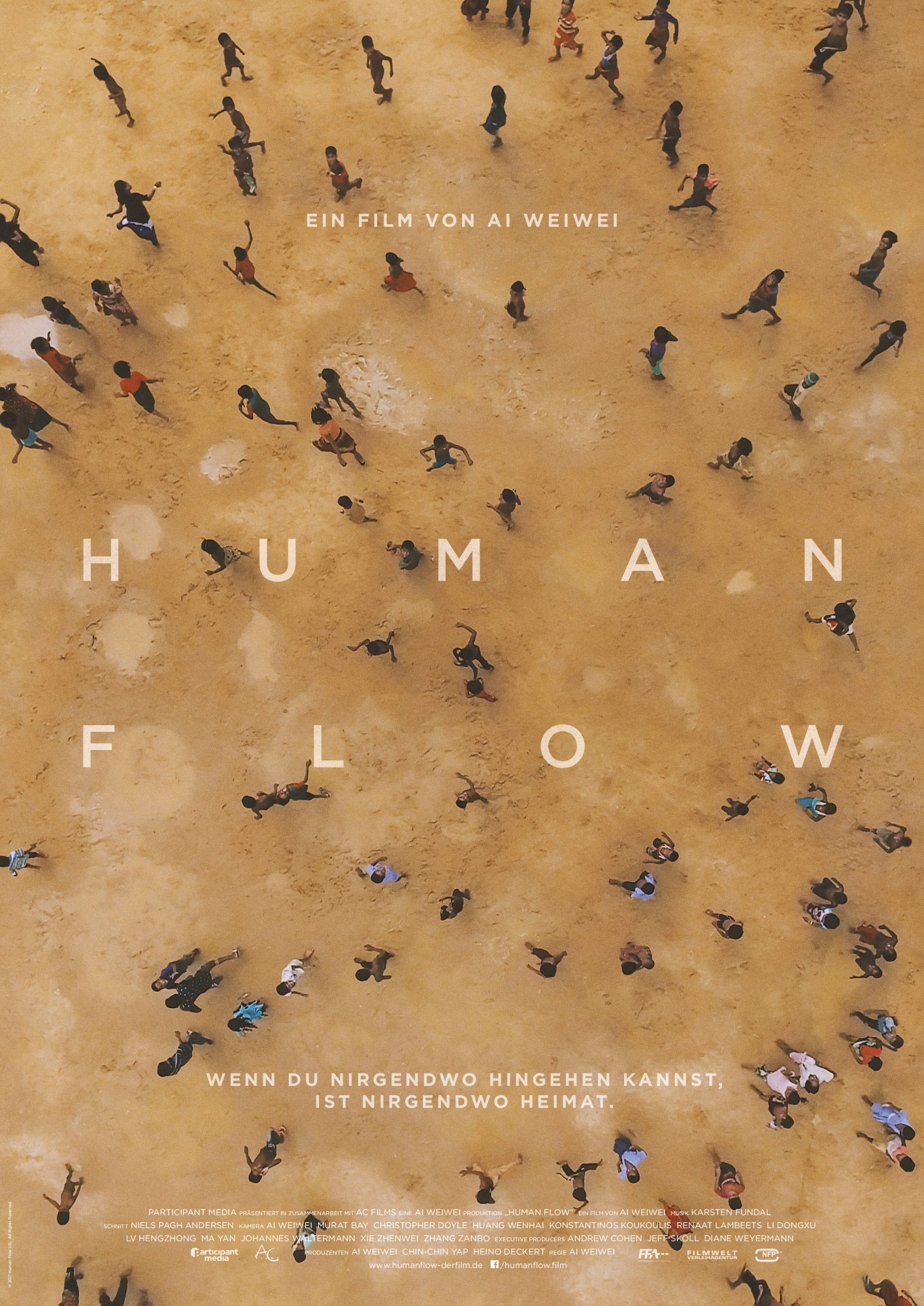

“When there is nowhere to go, nowhere is home,” reads the new film poster for Human Flow, Ai Weiwei’s latest movie. Not only does the quote refer to the current refugee crisis — which Weiwei calls a “human crisis” — it also applies to the artist himself. Ever since the documentary Ai Weiwei: Never Sorry was released in 2012, it’s apparent that he, too, is a refugee. The director, Alison Klayman, documents Ai Weiwei’s release from prison in China, his arrest at the airport in Tokyo, and the destruction of his studio in Shanghai.

Back then, Weiwei was forced to leave his home country of China for political reasons. In an interview with i-D, the artist explained in his calm, slow voice that he doesn’t have a home — just like the 65 million people worldwide who have been violently driven from their homes. “It is the highest number since the end of World War II,” as we learn in Human Flow. Marrying facts with moving pictures of a journey around the world, and quotations from poets from the Middle East, Weiwei tries to pinpoint something that often goes unnoticed: the individual fate of each refugee.

“It’s not enough to only show the situation in Syria. You have to take a look at the [entirety of] human nature to see where it is coming from and how it could end like this.” That’s why the Chinese artist and activist traveled with his team to 23 different countries — including Syria, Greece, and Mexico — to bear witness to a situation he’d originally known little about, until he saw the tragedy of humanity with his very own eyes. Right before the release of Human Flow in Germany, i-D met with Weiwei in his studio in Berlin to discuss what each and every one of us can do to overcome this social crisis.

i-D: For your latest movie, you traveled to 23 different countries to see this human crisis with your own eyes. What was the biggest challenge on your journey?

Ai Weiwei: There were lots of problems, because you need a special team for every country. Everything had to be arranged because we had to be super punctual to get to everywhere to integrate the people — whether officers, smugglers, or refugees — in the camps. Sometimes it can get quite dangerous, but the most difficult part was actually leaving the camps after all the interviews, knowing that I didn’t really help [anyone]. I had to keep telling myself that the movie would serve its purpose later, and hopefully raise awareness among people.

You wanted to put a face to the statistics about refugees and tell their individual stories. What’s the message you want to convey with your movie?

The movie is the message. We have to ask ourselves why it was necessary to make this kind of movie in the first place; after all, the topic is [discussed] a lot in the media. But Human Flow tries to understand [the situation] instead of recreating fragmentary descriptions of [it]. And that’s necessary, because you have to see these things in order to understand the human struggle. The pictures are too fragmental, and that makes it difficult to see what’s really behind these situations. We don’t get a lot of information about that, especially not through the mainstream media. Many people have been in the camps for three generations, so they basically spend their entire lives as refugees. They’re suffering, we all know that, but we don’t reach out to them. The world should be one but it doesn’t behave that way. It is broken.

On the film poster reads the following quote: “When there is nowhere to go, nowhere is home.” You also had to leave China for political reasons. Does this sentence speak to you?

Yes, I think it reflects the concept of home. It’s a place where there’s more tolerance and where you are accepted as a whole and not rejected. If your home is against you, it no longer is your home. In my home country, I’ve never been accepted. They put me into prison, beat me, and exiled me. Now I’m in Germany and I’ve chosen freedom — even though, at the same time, it’s a very limited freedom if you don’t speak the language.

What does home mean to you?

I have no home. I’ve never felt like I could go home — not even in the most private situations when I visited my parents. For political reasons, they’re living at constant risk, their entire lives, and that’s why I’m not safe with them either.

You’ve been imprisoned for more than 80 days and were left with nothing more but your own thoughts. What did you realize during that extreme situation?

I realized that the worst situation is not the one where you’re beaten, locked up, or considered an enemy, but the one where you’re deprived of any kind of communication. During that kind of arrest you lose your entire vocabulary, because there’s no way you can talk to someone — not even the guards. So you have to learn an entirely new vocabulary: Each movement and each look [takes on] a completely new meaning. It’s very hard to accept that — and that’s exactly what all refugees experience when they come to a foreign country.

What can each and every one of us do to stop this human crisis, as you call it?

We’ve always hoped and thought that in the 21st century, we would have better conditions through globalization and greater tolerance regarding political situations. But today there are more borders than ever and it seems as if we’re strongly divided. We have to start really dealing with this situation instead of repressing it.

I believe that all these crises are man-made, so man has to find a solution now. We all have to believe that we have the power to bring about change. If we lose that faith, we will also lose our hope, our trust, and our humanity.