This article originally appeared in i-D’s The New Fashion Rebels Issue, no. 352, Summer 2018.

By the time of the 2007 riots in Nørrebro, Copenhagen — prompted by the Danish government selling the notorious Youth House squat to a far right Christian sect — 15-year-old local Elias Bender Rønnenfelt had already resolved in his own way to smash the system. Elias is the singer of the propulsive rock band Iceage, who are currently prepped to release their exquisite fourth record, Beyondless.

“The years leading up to the riots were my formative years,” he says, drinking an impressive midday pint of Stella Artois in Hackney Central Wetherspoons one spring Monday. “My neighbourhood was a very eclectic, radicalised place.” Inside Elias’s teenage bedroom, ideas both cerebral and muscularly musical were germinating hard and fast.

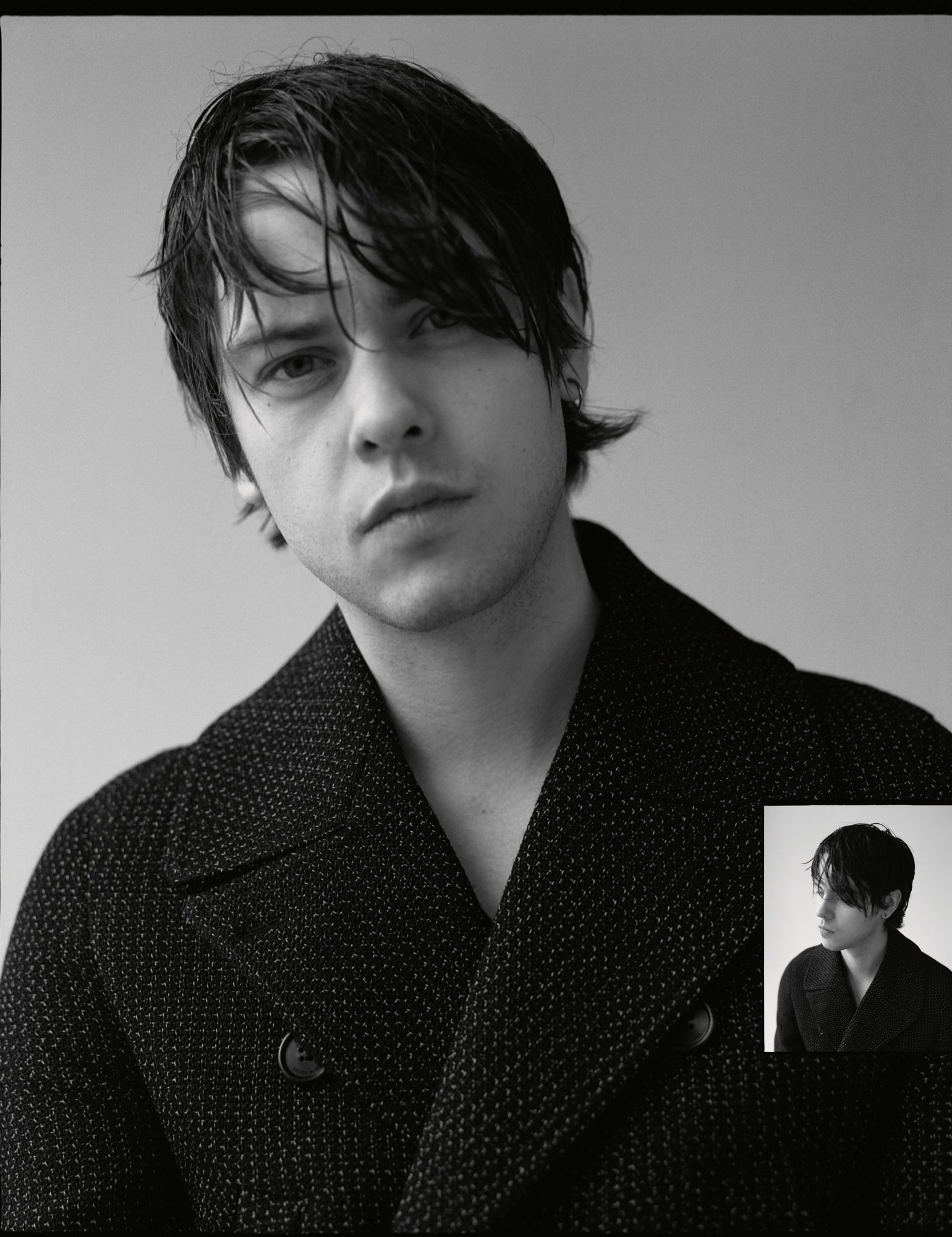

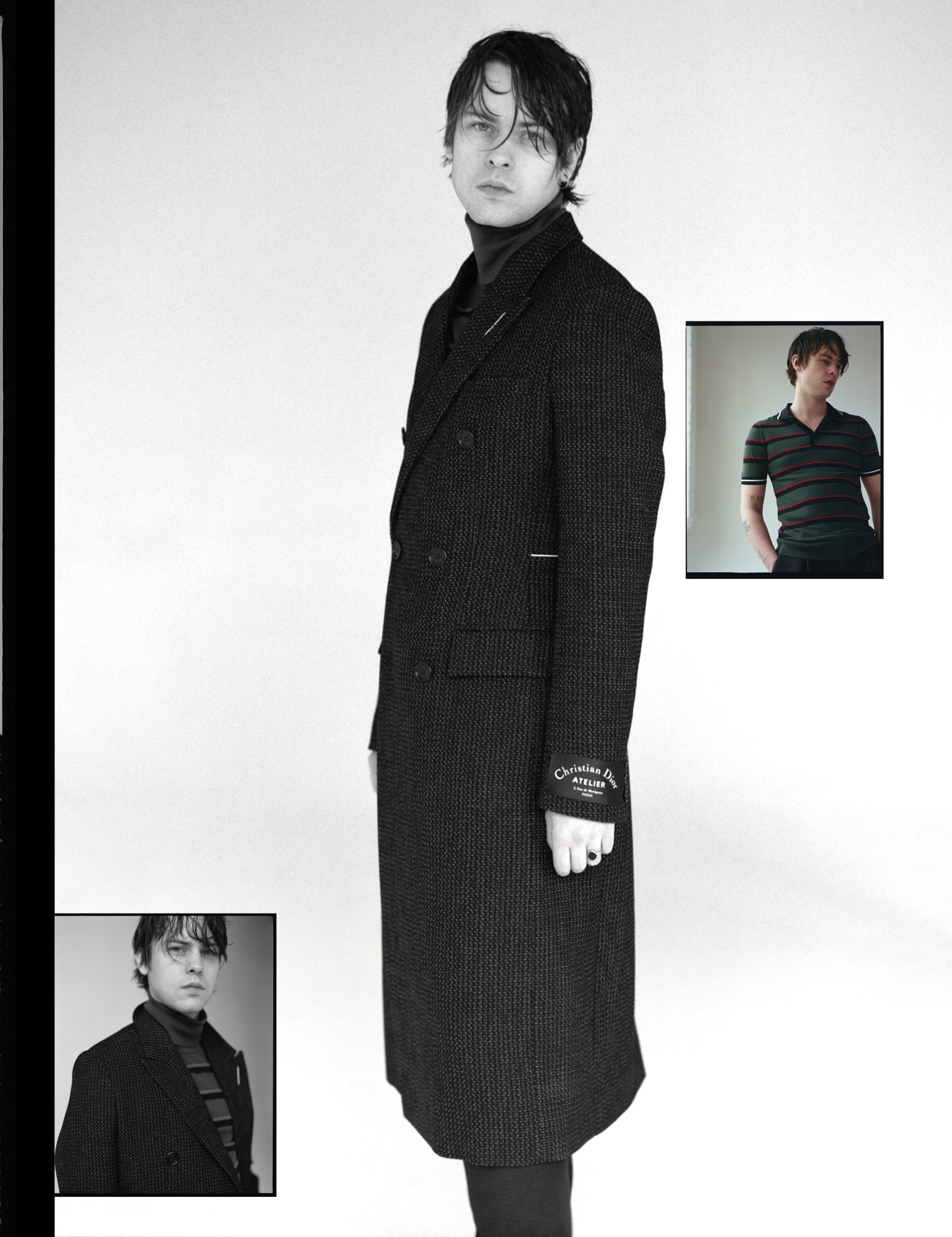

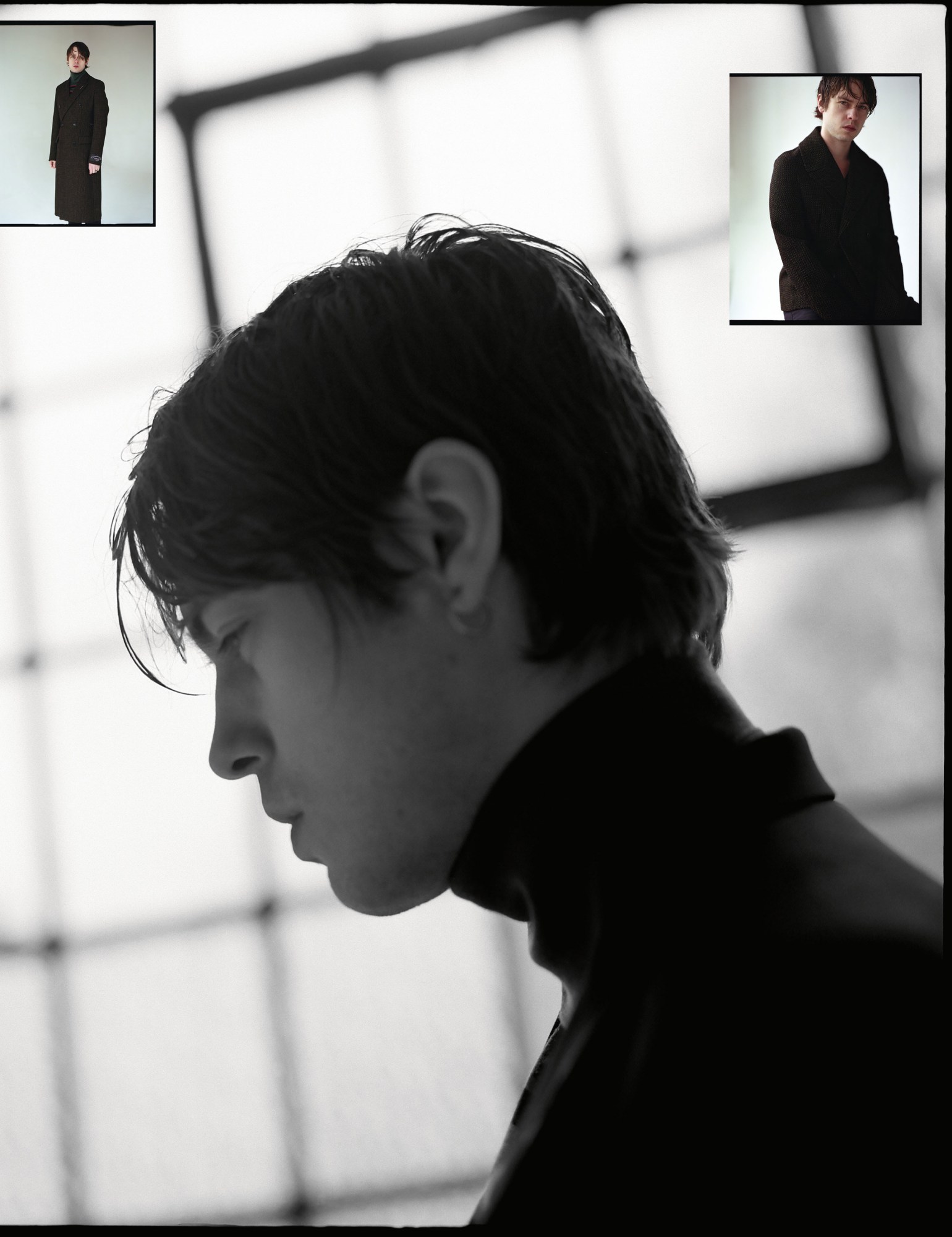

Elias is a rewardingly taciturn subject. He looks as if he’s been carved from the gods, a face sculpted with soft features and hard expressions. He’s a prepossessing, formidable figure who reminds you of a different epoch’s idea of the frontman’s responsibility, an irrational demand to be looked at. To reinforce the timeless nature of its endeavour, Beyondless arrives with a personal endorsement from Richard Hell and a contextualising quote appropriately robbed from Jean Genet’s The Thief’s Journal. “What we do,” he notes at one point, “is extremely traditional. Our relevance doesn’t lie in our ability to innovate. It lies in its soul.”

The riots on his doorstep as a teenager, the biggest display of public disquiet Denmark had seen in decades (The Guardian headline: “Anarchy in the DK”) and one in which up to 700 mostly teenage arrests were made, appears to have formalised the outlier in Elias. Prior to the event, he says, “you’d get into all sorts of meetings, everything from creating paint-bombs to very dry, boring discussions about the Bolsheviks. There was a lot of grassroots activism around.”

The young Elias was closely acquainted with every groove of The Stooges’ Funhouse and Raw Power. He’d found and embraced the work of local punk heroes, Sods, aged 12 and become transfixed by the power of their guitarist Peter Schneidermann, who took him under his creative wing after Elias introduced himself at a gig by Peter’s early 00s band The Bleeder Group. “That something being created out of Denmark could speak to me maybe subconsciously gives you a boost of confidence.”

Schneidermann encouraged Elias to forge his own education. He began truanting from school, and hanging out in his studio while Schneidermann crafted the soundtracks to early Nicolas Winding Refn films, taking home bootleg DVDs of work by Crispin Glover and Larry Clark. So taken was he by this unusual urchin charge that he personally booked the studio time for Iceage to record their first 12” single.

“The motivation was to break with punk. Not necessarily out of spite, but because this thing I was looking for didn’t exist. I was trying to find something of my own.”

Elias says the band were formed from the classic punk language of disenfranchisement. “Copenhagen has always had a thriving punk scene, in the more traditional sense, and that environment was inviting to me. But it also wasn’t what I was looking for because it was so traditional. The motivation was to break with that tradition. Not necessarily to spite them, but because this thing I was looking for didn’t exist.” Around him there was nothing that he could look at to satisfy his artistic leanings. So he invented them. “I was trying to find something of my own.”

He says the early Iceage shows were ramshackle occasions. “We never wanted to do the whole band thing. We were just snotty-nosed kids killing boredom.” He isn’t sure how he felt about being looked at back then. “In the beginning I was oblivious to it.” As teenagers, they had no idea of the potential reach of the band. Nor did they care. “When you grow up thinking that the culture around you doesn’t do it for you and you see a lot of things that frustrate you because it’s not what you want, the best thing might be to smash that world up.” That wheel continues to turn.

The full blossom of Iceage has happened satisfyingly speedily. The journey to Beyondless includes three records of their own, New Brigade (2011) and You’re Nothing (2013), both incendiary, noisey and anthemic visions of hardcore punk, and Plowing Into The Field of Love (2014), which slowed their sound down, into more emotional territory. Elias has made extra use of his time away from the central project in his esoteric offshoots, Vår and Marching Church. The progress toward Beyondless — what may yet turn out to be their masterpiece — feels particular when listened to in the context of the band’s canon of work.

Elias spent a year cultivating the brilliant ideas for Beyondless before borrowing a friend’s workspace to formalise his thoughts prior to recording. Iceage in the studio, he says, is about finding a place of danger. Because they have played together since their youth, there is an intuition to it, “a sort of seasickness between the drums and the bass” as he describes it. The record is ten electric songs long. New references are brought in, most notably a pile-driving take on Jacques Brel on the swaggering penultimate track, Showtime.

Despite its sheer force, the record feels romantic, sexy even. “I don’t know how deliberately sexy it is,” he says. “But I don’t disagree with that term.” It’s easy for a band to be propelled by sex as teenagers, but sometimes it only starts to manifest at full effect in their 20s. “You can argue that we are playing a bit more from the hip rather than the chest. I don’t really want to elaborate more than that.”

Elias is proud of the record. “Yes,” he says slowly, quietly. “It’s not that we want to write ourselves into a lineage, but it’s certainly informed by 100 years of musical tradition. Songwriting as a pursuit is something that we’ve realised, as we’ve been going on, that we are interested in. The song.” It has come as something of a surprise to them all. “We went into it out of sheer intuition.” In some sense, all of Iceage has come as a surprise to Elias. “The fact that we had written enough songs to put on a 12” was pretty wild for us. I don’t think we realised that it could reach anyone outside of Copenhagen.” When it did, there was no sense of congratulating themselves. “We didn’t have an attitude of, yeah, we’re making it, we’re breaking into the music world. We were more apathetic towards it. We put our guards up.”

They were 18 years old. “For people like us, maybe we subconsciously needed to have a certain amount of healthy spite towards what was going on around us. I’m not talking about the people identifying with the music. That was mind-blowing. That passion was so nice to see but there were so many other parts to it, especially the music industry.” The words are practically spat out. “We had a certain amount of spite towards everything until we… well, there’s probably a bit of spite left in there. You learn how to map out things and not fall into any of the easy traps. Or maybe we fell into a bunch of them and survived.”

Credits

Photography Anna Victoria Best

Styling Max Clark

Hair Blake Henderson

Photography assistance Philip White

Styling assistance Louis Prier Tisdall