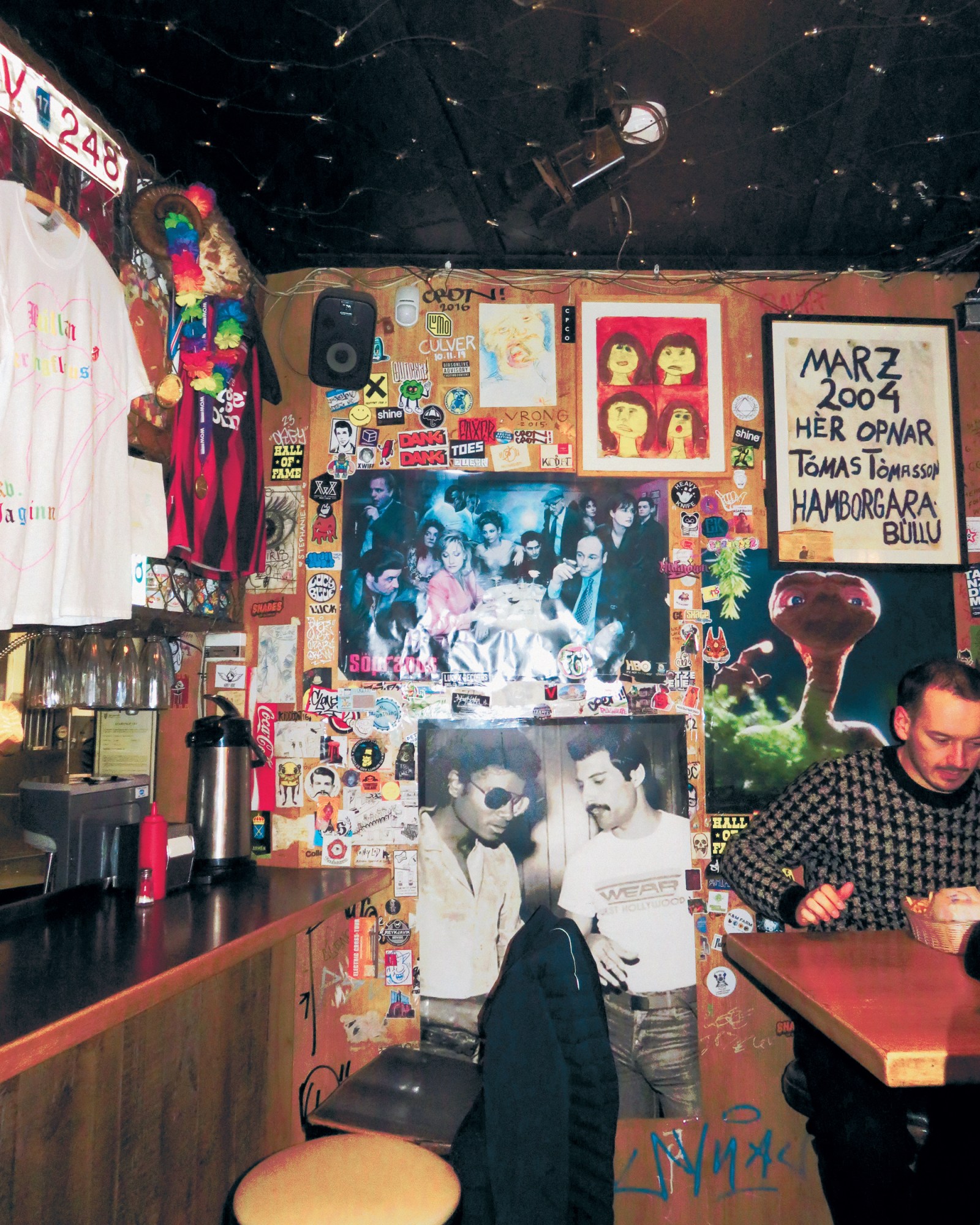

In a country where alcohol is notoriously expensive, it checks out that Reykjavík locals love a happy hour. When the festival Iceland Airwaves is on, happy hours also turn out to be a great place to meet new bands. During one at Bingo, a “drinkery” on the city’s famed rainbow street, I meet a high octane stranger with a near-translucently blonde buzzcut, who I later find out is part of Inspector Spacetime, a local band who bagged a Band of the Year award in 2022. We soon dash off and head for a shawarma around the corner. While sitting down at Kebab Sara, with garlic sauce dripping down our hands, he and his friends tell me to come catch their sets, listing places I cannot possibly write down correctly on the spot: Gaukurinn and Lækjartorg. Luckily there’s a buzz around both acts, so it’s not hard to track them down.

The next morning, after being knocked out by a mere two Icelandic pints, the wind nearly blows me off my feet as I walk towards an old folks’ home just outside the centre, where the 25th edition of the festival is formally opened. The nursing home is near a locally-loved graveyard and is definitely not a music venue. I rub shoulders with a 90-year-old lady as the minister of culture, Lilja Alfreðsdóttir, delivers a speech. “Don’t be afraid of the weather,” she says. “It’s what makes us strong, resilient and creative.”

Iceland Airwaves is compelling because you don’t just get a line-up of typical names – it books artists across pop, indie, rock, metal and electronic. Roughly half the bands who play during three days are from the international circuit – including Mary in the Junkyard, Magdalena Bay, Lambrini Girls and Personal Trainer – but as a foreigner, you grab the plane for the diverse homegrown talent. And, of course, to try to catch a glimpse of the Northern Lights and jump in one of the many hot springs.

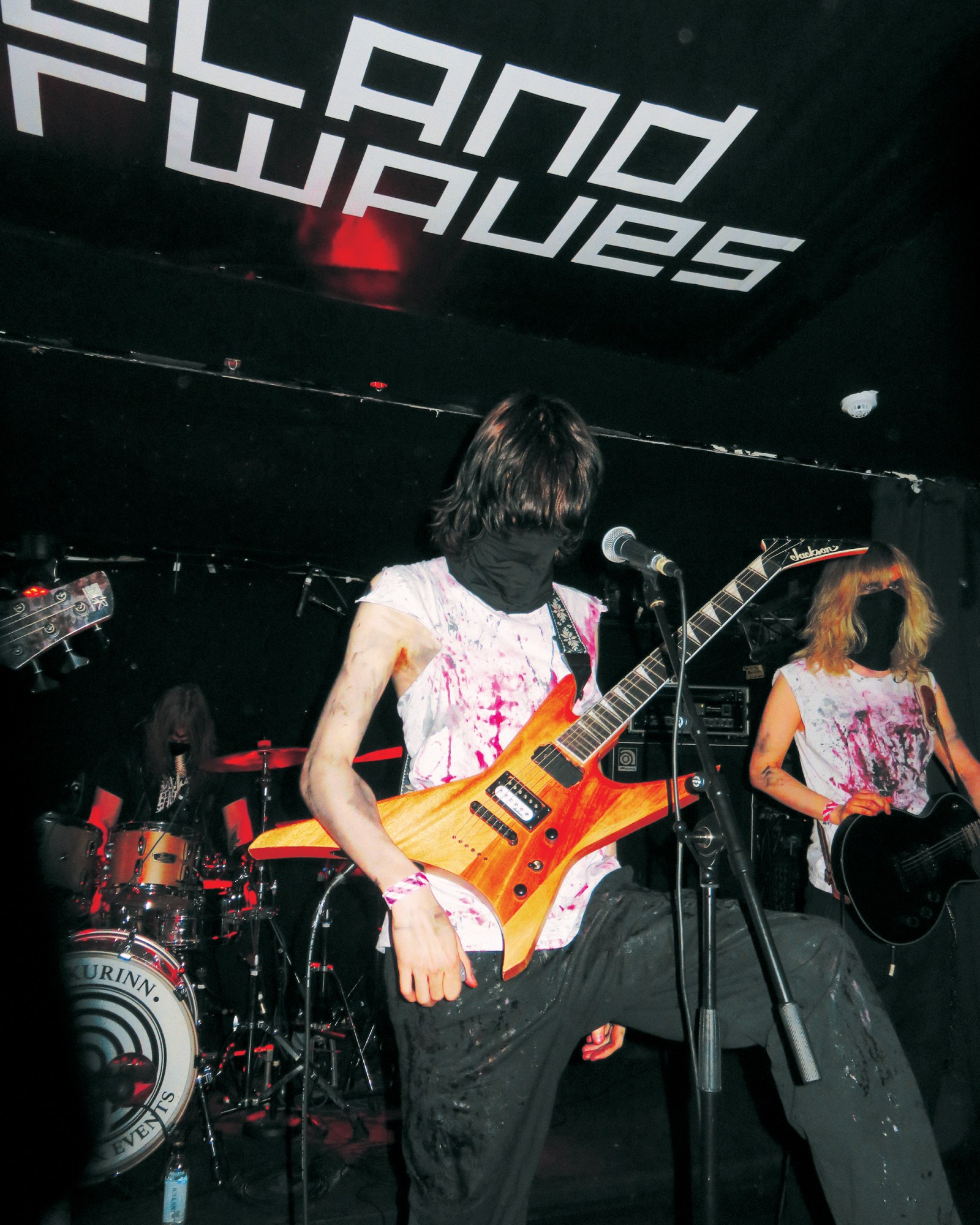

I lost my black metal virginity listening to Vampíra at 7pm on the first night – an atmospheric band with hints of goth – before dashing off to see the much hyped art-pop project Supersport!, whose enigmatic frontman Bjarni Daníel Þorvaldsson croons and dances jerkily like Thom Yorke. Later, as I conspicuously sip duty-free whiskey from a thermos, I’m deeply enthralled by Berlin artist Uche Yara, whose voice makes me question if she uses a pitch-shifter on stage (as it turns out, she doesn’t). Like Caroline Polachek, who’s technically skilled enough to make her voice sound like autotune, Uche seamlessly swings from a high register to the depths of a 60s Sarah Vaughan.

Running between four venues and twenty artists each night may sound exhausting – it certainly would be if you were at Glastonbury and tied to a large crew of friends – but it isn’t when you’re flying solo and the venues are all two minutes from each other. Hunger strikes at 9pm and I dash to the port-side restaurant Seabaron, a small local haunt famous for its relatively inexpensive lobster soup. As I open the creaky door and step inside, I join a Californian I just met hours earlier. We did not arrange this rendezvous. She’s in the middle of sharing her life story with a total stranger from Buffalo, New York, while munching on seafood skewers. Naturally, I join. (We avoid the obvious topic on any American’s mind that day: the election.) About twenty minutes later my lobster soup is shaking violently in my stomach as I enter the moshpit at the Icelandic hardcore band Une Misère’s show. When my head hits the pillow past midnight, I know I totally missed the Northern Lights.

Before music started each day, I joined a few of the festival’s panel discussions, including a compelling talk titled “Shut up and play: Artistic integrity and commercialism”. It dealt with questions everyone seems to be asking right now: Is there space for dissidence in today’s hyper-capitalised music industry? Can all artists afford to speak up, or is this privilege reserved for a few? AJ, a promoter from Beijing, spoke about the Chinese Communist Party’s influence on both local and international music while Diana Burkot of Pussy Riot lamented how Russia’s stifling regime leads to self-censorship across the board. “Totalitarianism is on the rise worldwide,” reflected moderator Anna Hildur. The solution for artists? Be subversive through a show-don’t-tell approach. “We cannot be out of politics, we cannot escape it,” Burkot said. “Please try to figure out what’s going on in your country and be active in what’s up in your country and life.” The program highlighted the festival’s commitment to engaging in dynamic conversations about the state of the industry, with panelists from all over the world – an approach you don’t often find at festivals.

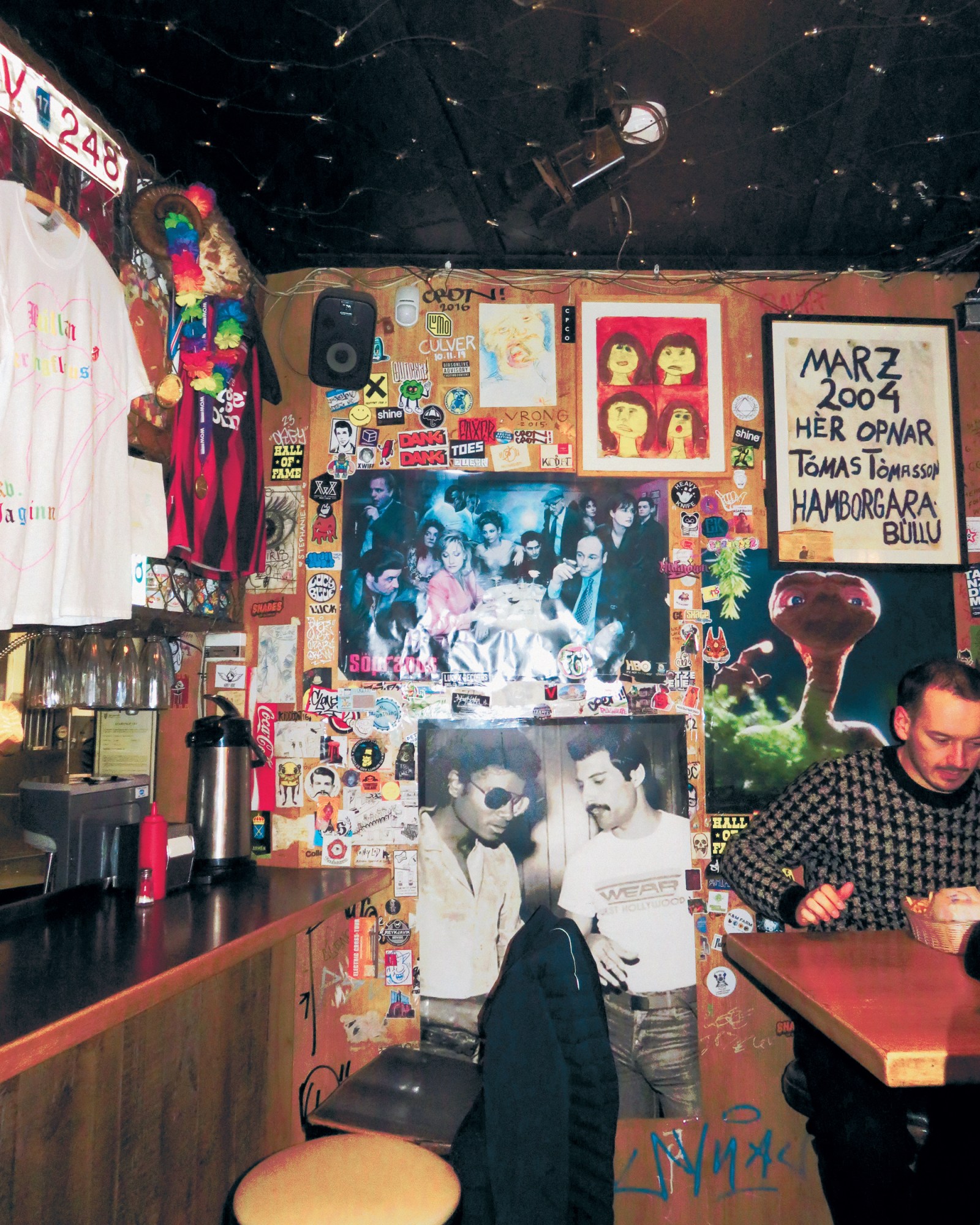

More than 80 acts play “officially” from 7pm each night, but there’s at least the same amount of shows happening outside main venues throughout the day. The festival shares an extra events schedule, which features gigs at record shops and breweries, but there’s also the off off-schedule – where the cool Icelandic kids are at. They’re gigs, documentary screenings and parties which are a little harder to find because they aren’t clearly advertised. You’ll instead discover them through talking with locals or randomly stumbling upon them walking down the street. Word-of-mouth was how I found out about Amor Vincit Omnia’s show, a Grimesy electro-pop project by two of the blondes I met at Bingo. Playing in the foyer of arthouse cinema Bíóparadis, the crowd of 20-somethings were dressed up in bathing robes, night gowns and other sleepover props, seemingly just for fun. One gig-goer was dressed up as a nighttable, complete with condoms, a Tolkien book and Strepsils.

But then what to do with spare time between shows, if ever there was such a moment? Make a local friend to show you around. A woman named Lilja, who I met 48 hours earlier, introduced me to the swimming pools all locals swear by, guiding me through the hot-cold-hot-cold ritual. It affirms why everybody recommends this as a hangover cure. More on the locals: they really do support locals. At many of these off-schedule venues with a capacity of 30 max, main-stage artists like Bjarni from Supersport! supported new blood like MC Myasnoi’s doom electro-rock. Perhaps that’s because the population in Reykjavik is 140,000 people, which is roughly half of Hackney. You would support your neighbour, wouldn’t you?

Credits

Words and Photos: Jorinde Croese