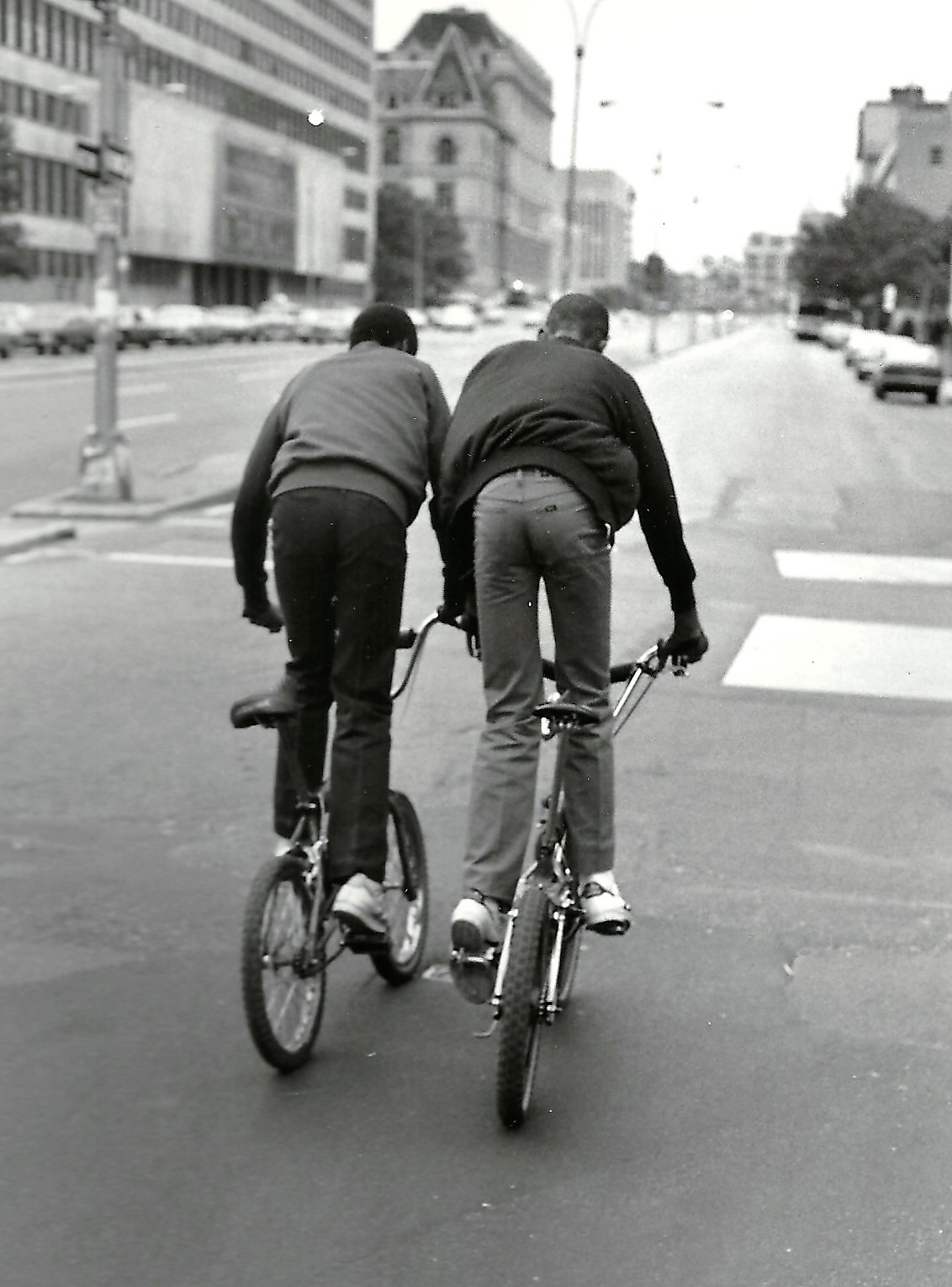

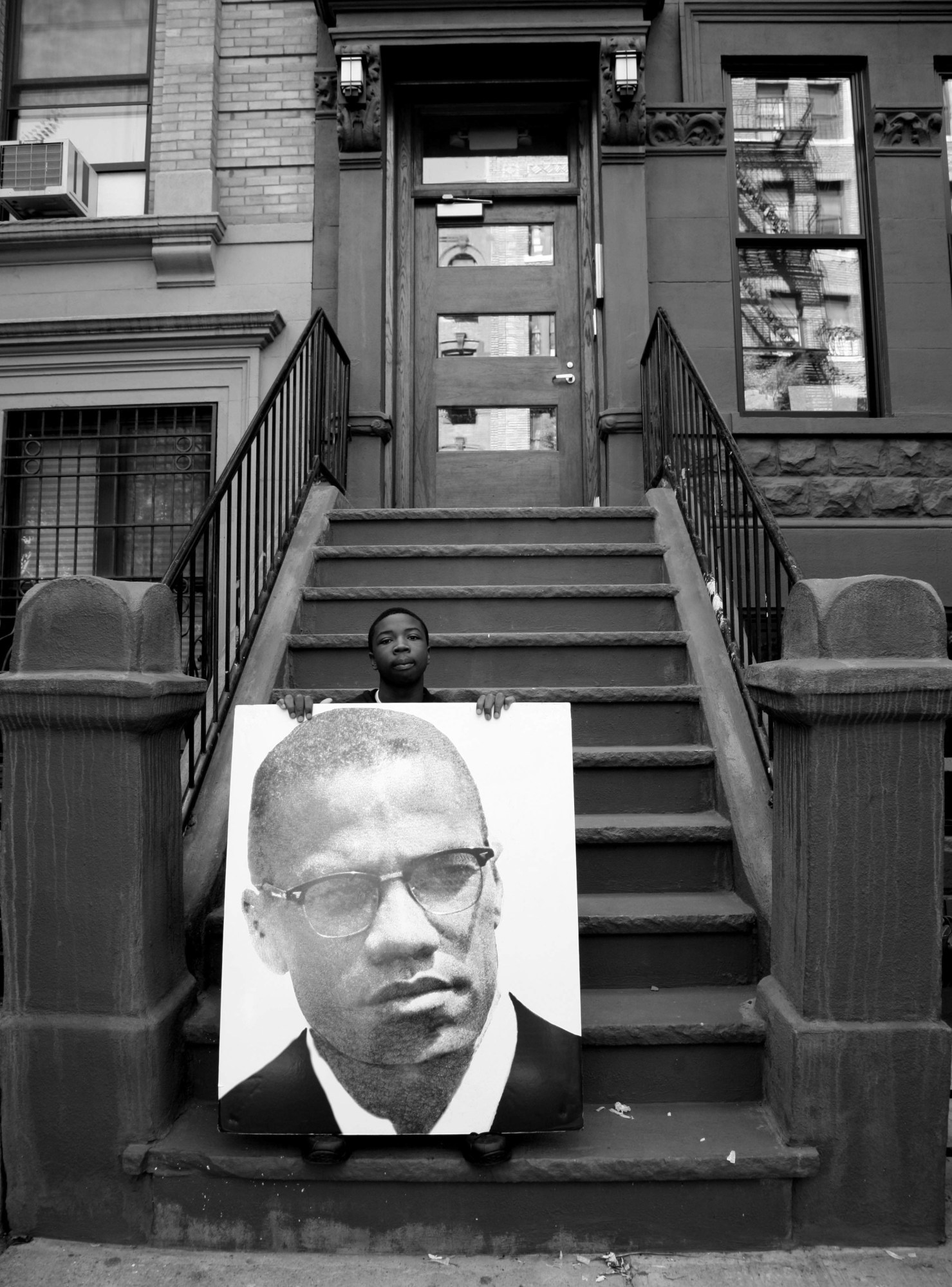

Cheryl Dunn’s 2013 documentary Everybody Street is required viewing for anyone remotely interested in street photography, New York City, or other human beings. Jamel Shabazz — one of the 13 iconic photographers the film features — is a passionate scholar of all three. In Everybody Street, the Brooklyn native shares the stories behind some of his most acclaimed work: portraits of young black New Yorkers, some standing with their friends, many smiling and proud. The pictures were largely made in the 1980s, often in Shabazz’s own Flatbush neighborhood, or in bustling Downtown Brooklyn.

Shabazz not only recorded the New York of the era — the subway cars covered in elaborate graffiti, Times Square full of cheap movie theaters — but the New Yorkers of the era. These images occupy the magical space between documentary and fashion portraiture, which is in part why they’ve become so cherished in the fashion industry. (Considering his last collection featured many of the same styles Shabazz photographed in the 80s — bucket hats, pressed slacks, gold chains, and seriously enviable coats — is it any wonder Marc Jacobs recently hosted a signing with the photographer?). As iconic and important as these pictures have become, posed portraiture is not Shabazz’s only style.

Earlier this week Shabazz released a new book, Sights in the City. The work collects more than 100 images Shabazz made over almost four decades, many of them never-before-published. While some of its photographs are posed portraits, the book mostly features unplanned street snaps. Shabazz finds humor, pathos, and magic in split-second moments at parks, protests, and parades. He’s eternally mining for gold among New York City’s alchemical chaos, and in the process, enriching us all. To celebrate Sights in the City‘s release, we spoke about Everybody Street, social media, and Mary Ellen Mark.

Sights in the City opens with an interview between you and Cheryl Dunn. How did Everybody Street shape your approach to making this book?

First and foremost, I am very grateful to Cheryl for inviting me to share my thoughts in this insightful documentary. After viewing Everybody Street, I realized that my particular segment was somewhat limited in regards to my overall view on street photography. So, much of what I addressed was centered on asking my subjects for permission to photograph them. In retrospect, I would have given a more balanced perspective on the subject of posed and unposed images, along with the issue of asking for one’s consent. With that said, I felt that it was time to put forth a monograph entirely devoted to New York City street photography —a book that will give the viewer a more comprehensive look into my practice. Since the conversation on street photography was first addressed with Cheryl in her documentary, I thought it was only befitting to have her participate in the Q and A.

In Everybody Street, you discuss your approach to making portraits —creating a joyful and empowering exchange between yourself and your subjects through dialogue. Yet Sights in the City largely consists of unposed photographs. How do you approach this more spontaneous style of street photography?

Great observation! My work is equally divided between my traditional posed images and spontaneous street captures. In all of my published works, you will see a combination of both practices. My father, who was my main photography instructor, was never keen on posed images and often critiqued them harshly when I presented them to him. He would tell me that it is better to focus more on capturing the “decisive moments.” I took heed to his instructions, but always stayed true to creating posed images as well, because that was something I enjoyed doing and it was a reflection of the exchanges I had with my subjects. So in the 35 plus years that I have been making images, I sought to create two unique bodies of work, consisting of posed and unposed images. [I’ve favored] more spontaneous images in my more recent practices. The approach was pretty much the same: all about having the camera out and at the ready and being observant and respectful.

This book spans nearly four decades. In one photograph, taken in 2010, a group from the show 106 & Park is dressed in 80s throwback style. Fashion is cyclical, but does it ever feel strange to you — as such a vital documentarian of that era’s sartorial expression — to see these styles resurface so many years later?

I often find it quite interesting to see styles from the past resurfacing. In my exchanges with young people who embrace the retro look and styles, I find that they have a deep connection and appreciation for 80s fashion to the point that many of them wished they had lived during that time period. Others have told me that they embrace that way of dress partially because their parents grew up wearing similar styles. So when I see these throwback looks, it warms my heart knowing that the styles and fashion of my era are still greatly appreciated. In addition, a number of adults from my generation —many in their late 40s and 50s —still wear styles from the 1970s and 80s. For them, it means holding on to a special moment in time that helped to shape them.

You’ve included a picture of Mary Ellen Mark, who was also featured in Everybody Street, in Sights in the City. Why?

Mary Ellen Mark was one of the best street photographers ever. On several occasions, we crossed paths in the streets — from the West Indian Day Parade in Brooklyn to various public celebrations in the city, where she would always be there working her magic. I was first introduced to her work back in the late 1970s when I read about her in a Time Life photography book that she was featured in. It was there that I became acquainted with her style of shooting and practice. I appreciated the subjects that she opted to document, from the poor city kids of Seattle to twins. The love between her and her subjects was apparent, and I admired her for bringing that out. Mary Ellen Mark was dedicated to the craft and was tough.

One incident I vividly remember is when we bumped heads one day when she came upon me making a portrait of a couple in Harlem and tried to take the same image. I nudged her gently with my shoulder to let her know that I didn’t appreciate her taking the photo of a subject I worked hard to convince to stand in front of my lens and pose. Now she was going to casually take the same image, and I didn’t take too kindly to her or anyone else doing that. So when I nudged her, to my surprise she gave me a slight push right back, without even giving it a second thought. It could have turned into a serious situation, but I let it go and would later make the portrait you see of her in Sights in the City.

You’ve spoken about the power and importance of photography in its relation to memory making. Do you feel that relationship has changed in the digital age?

In today’s world, memories are now endless, unlike when I was coming up, when only a very few had decent cameras and the ability to make good images. Today, with the advancement of technology and social media, image making and sharing has never been such an important aspect of everyday life. What I find most interesting about it, is that there is a deep interest in photography like never before, and I am actually seeing a lot of good work. Now, almost anyone can be an image-maker or storyteller. And what I am seeing more of than when I first picked up the camera, is that there are countless stories being told by these often novice photographers. So, I embrace and salute this new generation of image-makers.

You’ve also discussed how your military service in Germany impacted your life back in Brooklyn — that upon returning in the 1980s, you felt compelled to help other young people focus their energy outside of destructive behaviors. What advice would you share with today’s young people?

My advice to young people today is to prepare for the future. Develop a set of goals and objectives that you seek to achieve, and work on finding a mentor that can help to guide you along the way. We have all been blessed with internal gifts, so search within you and find that passion, develop it, and forge ahead. I believe that we all have been put on this planet for a reason. Let us work with great zeal to create a legacy that can both inspire and make this world a better place.

Sights in the Cityis available now.

Credits

Text Emily Manning

Photography courtesy and copyright Jamel Shabazz