When she captured her iconic Self-Portrait/Cutting in 1993, Catherine Opie was longing for a life that felt out of reach . Depicting the photographer with her bare back facing the camera, the visceral image centers on a childlike scene of a house and two skirt-clad stick figures holding hands, carved into her skin with her own blood. Then in her early thirties, Catherine had already found a community in Los Angeles – the lesbian leather-culture circles that appear throughout her pictures from that decade – but a deeper yearning for another type of family led her to turn the lens on herself, a statement she intended as both personal and political.

“It’s hard to be a dyke-artist without including both of those elements, because the notion is embodied in our very being and in our relationship to otherness,” Catherine tells me. “I was going through a breakup at the time – my very first domestic relationship – with a woman named Pam, whom I was madly in love with. Simultaneously, I had friends who were dying of AIDS. It was a really important piece for me about my own desire and my friends in relation to death, what was happening in the community, and what blood represented on all these different levels.”

Self-Portrait/Cutting spoke to a particular moment in history, made amidst the 90s culture wars fueled by reactionary figures like Jesse Helms. In 1989, the Republican senator introduced a law banning the National Endowment for the Arts from funding any “obscene” art, citing photographer Robert Mapplethorpe as the epitome of ‘”morally reprehensible trash.” With same-sex marriage illegal and homophobia widespread, most queer people had complex feelings surrounding the concept of home. “I really wanted lesbian domesticity, to have kids and a house,“ Catherine says. “When I made the self-portrait, I also started to think more about what that meant to me.”

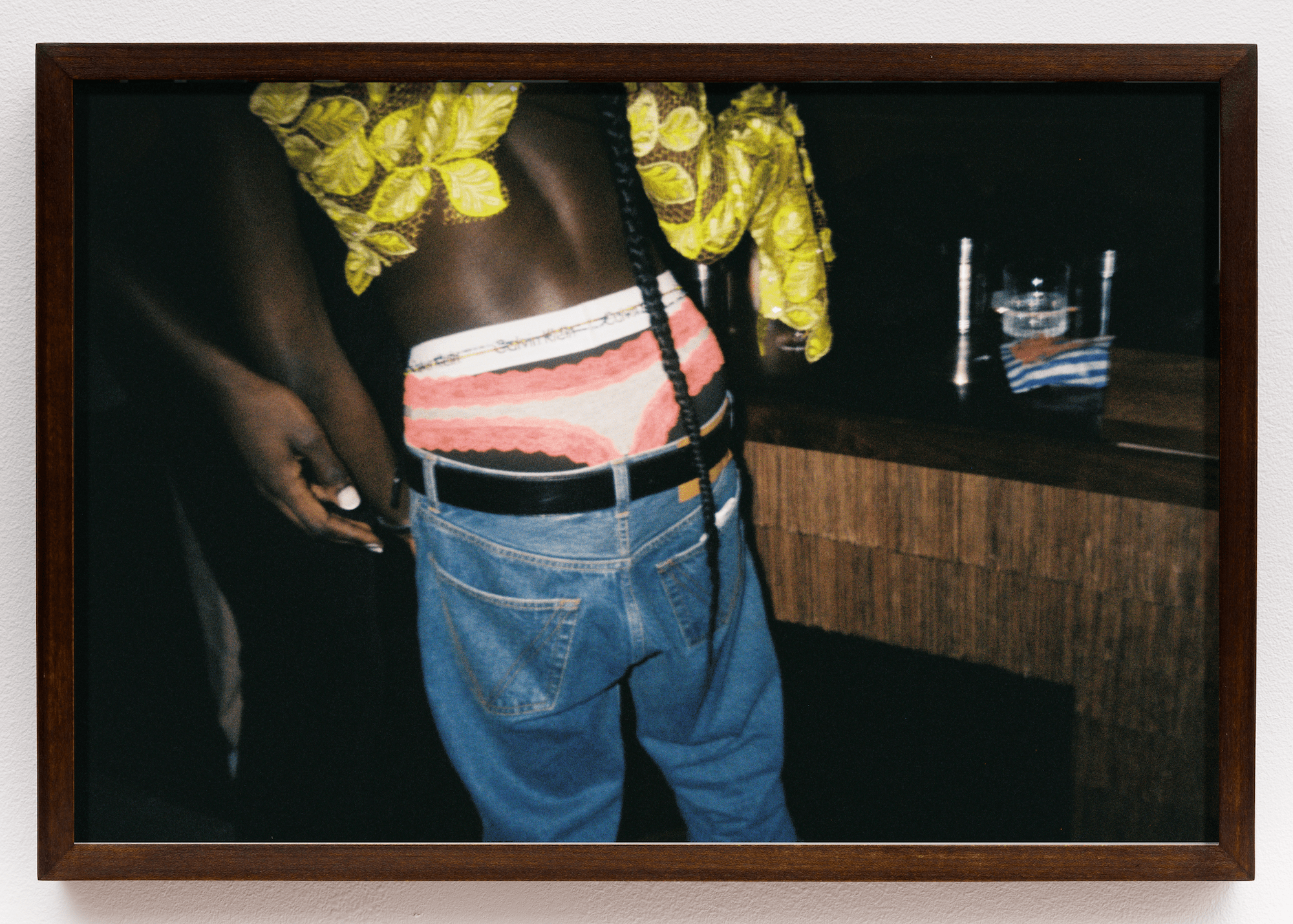

To commemorate the thirty-year anniversary of Catherine’s photo, a new group exhibition at the Leslie Lohman Museum in New York, Dreaming Of Home, uses the self-portrait as a jumping-off point to examine the idea of queer and trans domesticity. Featuring photographers such as Rene Matić, Laurence Philomene, and Whiskey Chow, in addition to other artists like Jenna Gribbon, Shadi Al-Atallah, and Leilah Babirye, each one follows Catherine’s example by emphasizing the body in their work, intertwining it with themes such as intimacy, parenthood, and migration.

“I approached the concept of home as a broad topic,” says Gemma Rolls-Bentley, the exhibition’s curator. “Does home mean safety, stability, a family, children? Is it about feeling at home in one’s own body, the embrace of others? Where does that feeling of belonging exist for queer and trans people?”

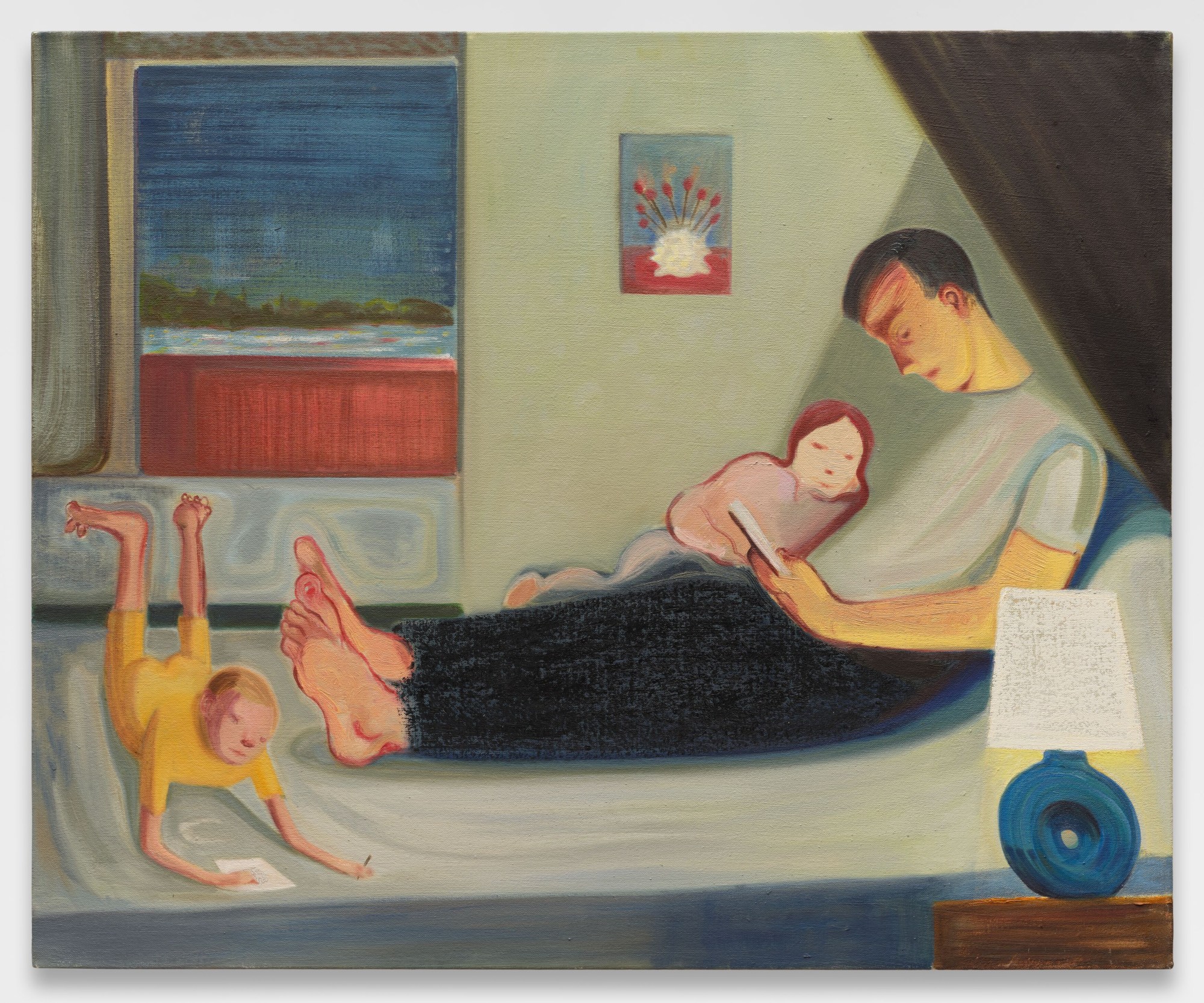

Dreaming Of Home spans a range of mixed media, bringing together works by animators like Danielle Brathwaite-Shirley, who explores the Black trans experience through a video game, as well as painters such as Nicole Eisenman, who interprets home as a cozy scene featuring a family at bedtime. Alongside queer love, the exhibit also highlights the barriers that gay people continue to encounter in certain parts of the world. In one tender photo by Charmaine Poh, we see a couple, Ele and Lee, lying on a bed covered in flower petals. Part of the photographer’s How They Love series, the image calls attention to the antiquated marriage and property laws in her native Singapore.

“Catherine was making images in a very different climate for LGBTQIA+ people, so it’s interesting to reflect on this 30-year period and see how radical her work still feels, then to put it in dialogue with other artists,” Gemma says. “We shouldn’t forget that many of the freedoms we now have as younger queer people are a result of the sacrifices made by our elders. Still, it feels like a very scary time to be queer, because there are so many new challenges that have arisen since she made that work.”

As anti-trans legislation threatens to force queer youth from their homes across America and countries such as Italy have started to remove lesbian mothers’ names from their children’s birth certificates, the questions posed by Dreaming Of Home feel all the more urgent, especially to Catherine. “I know I’m going to be a lifelong activist, and that’s great. All of us need to be lifelong activists – to vote, to use our minds, to try to make a change,” she says. “But what can I do beyond my role as an artist? It’s important I ask myself this. I can make work that’s in conversation with our ideology, but am I going to change someone who is homophobic through my work? No, I don’t have that kind of power.”

There is power in putting your truth out there, though, which is why Catherine’s self-portrait is so relevant today, inspiring subsequent generations of artists with its rawness and emotional intensity. In October, the Leslie Lohman Museum plans to honor the photographer for its annual gala — further proof of her impact on the LGBTQ+ community. When I ask her how it feels to reflect on the image now, as her perception of home has shifted over the years, she responds with some words of wisdom.

“Though we recently divorced, I had 21 amazing years with my wife Julie. We raised our son Oliver and had an incredible home,” she says. “I got to have the cutting on my back that I longed for. It was a great ride, but it ended, and that’s okay. That has its own painfulness to it.”

Self-Portrait/Cutting may evoke a sense of melancholy, but Catherine also offers a more optimistic reading. A closer look at the cloud carved on her back reveals a tiny sun peeking through, reminding us to maintain hope no matter the roadblocks ahead.

Dreaming Of Home is on view at the Leslie Lohman Museum until January 7th, 2024.