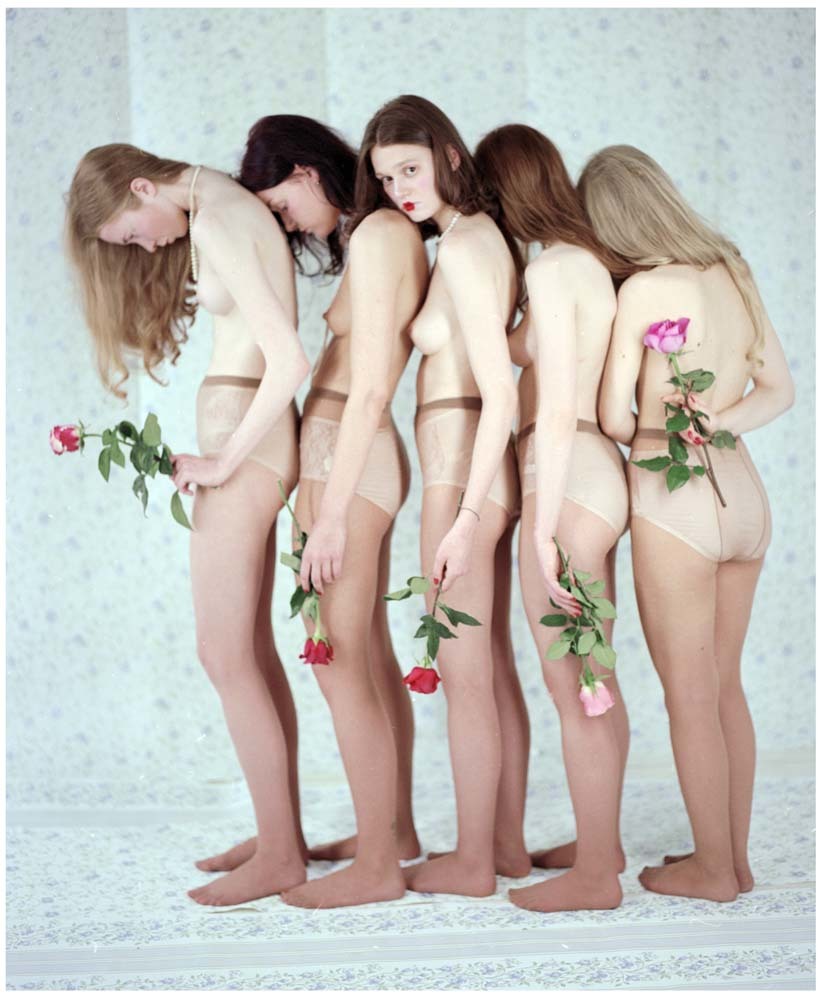

Through her images, captured with an analogue camera and taken all over the world, twenty-nine-year-old USSR-born art and fashion photographer Uldus Bakhtiozina reinterprets Russian folklore. Her bleak winterscapes and brilliantly-costumed characters skewer her country’s impressions of gender. Viewing the world through a distinctly Pre-Raphaelite lens, Uldus looks at the lives of regular people whose personal stories touch on the social issues of contemporary Russian society. These photographs are an attempt to understand the country’s rigid notions of masculinity and stifling ideas about what it means to be a woman.

This northern summer, she’s releasing her first photo book, Conjured Life, and in October will host a solo exhibition featuring new work in her hometown of St. Petersburg. We called her up on a warm Sunday, interrupting a visit to the countryside where she stages many of her shoots, to chat with her about how myths and legends can show us the real world.

Hey Uldus, why don’t you introduce your book?

The book will take the viewer through my journey of development as an artist. An edition of 150 copies will be published, covering works from the past three years with the series Desperate Romantics, Wonder Maria, Russ Land and my latest project, Land of Escapism.

What’s the story behind the cover image — the girl with big white moths crawling on her?

It’s from Russ Land and called “Milky Rivers and Kissel Shores.” It’s based on a mythological place often found in Slavic tales. It’s hidden in a land of beauty, with sleeping Tsarevnas [Russian princesses] and rivers made of milk and kissel [a pinkish drink from berries] shores. You can’t walk there, you can only arrive after a spiritual journey. It’s calm and full of magical features, like heaven. If a trespasser is caught, he’s turned into a moth. The Tsarevna is so full of light that the moths fly to her and become prisoners.

You grew up in a family of mixed backgrounds — with a Muslim father, Christian mother, and Jewish sister — yet your work has focused on mythology with Pagan roots. How did you get into Russian fairy tales and myths?

My mom was always reading fairy tales to me when I was little. Now I know them by heart. After you’re grown up, you look at them through adult eyes and you notice that stuff is missing. I started doing research and found that many of the names of the main characters were changed to have a negative meaning. For example, Baba Yaga is a shamanistic character who is supposed to be evil — someone who eats children. In the fairy tale she puts a kid in the oven and is about to cook him. But what I found was in Slavic culture people would put kids next to the oven to warm them up — they would kind of “bake them.” So Baba Yaga was actually probably really trying to help the boy, rather than harm him. Fairy tales weren’t written; they were told verbally. So each time someone retold the story, it changed.

It makes those stories difficult to preserve.

When Christianity came to Russia everything that was connected to nature became “bad.” Pagans believed the forest was something alive you could communicate with; whereas with Christianity that’s not possible, you can only talk with God. Christianity came to Russia by force, so history also heavily influenced the tales. Their origins are a complex thing, I wanted to show another side to them.

Your self portraits are also very reflective of Russian identity.

Yes — when I was living in London, I was in a car with my friends on the way to a party and they asked, ‘What do you want to drink?’ I’m not a big drinker so said I didn’t want anything, they were like, ‘What? You’re Russian!’ I replied, ‘Oh right, I drink vodka and I sell guns, and drugs, and child pornography.’ Humour was a good way to deal with it, because they saw how silly their prejudices were.

What motivates you?

I want Russians to feel proud of being Russian. Right now, the political situation is not very warm for us. Even when we travel, Russians pretend to be from other countries because they’re ashamed. It’s a very strange psychological issue of nationality, but it happens and we don’t talk about it. I want to change that, because we have such a rich history. I don’t want to say it’s my main goal in life, but I want to push young people to research and know their history and not only grow up on foreign movies.

How do young people respond to your work?

I receive a lot of emails from university students doing studies on my photos. I want to inspire them to make something or do something beautiful. Instead of creating something inside the country, we’re running away from it. I want them to see that it’s not only grey buildings and angry people. The young generation is different. We have a lot of creative people and designers. Beauty does exist here. Let’s keep it moving and growing. Let’s support that.

Credits

Text Mary Katharine Tramontana

Photography Uldus Bakhtiozina