Mental health affects everyone — and it’s important that we keep the discussion open. We are publishing this article to raise awareness around it, and to pay tribute to a wonderful friend and contributor, Matt Irwin. Before he died, he wrote a very eloquent and honest account of his struggle with depression in the form of an open letter to the world.

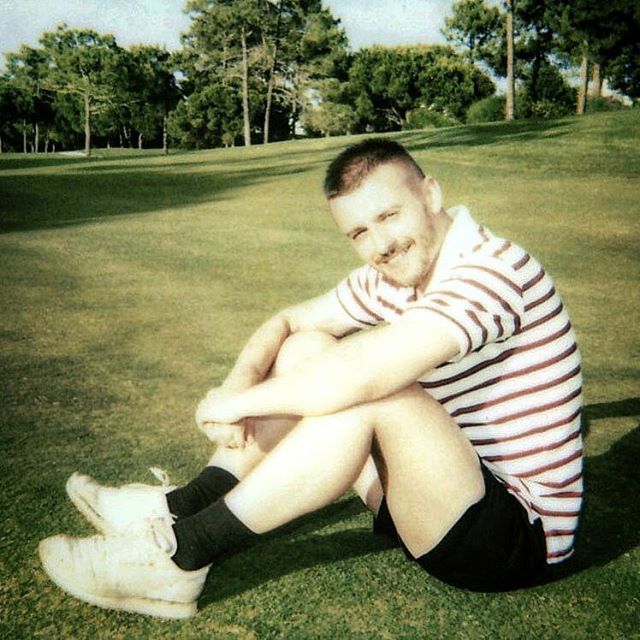

When Matt got the giggles, which was frequently, his shoulders hunched up and down, with a mirthful roll. He wore shorts most of the time, with rotten Reebok classics that occasionally smelled very bad. He had a blue vein on the back of his left ear and I used to look at it whenever he’d stand in front of me. He would bombard you with stills from Nighty Night, or video clips of He-Man singing St Etienne. He could fit The Legends of Zelda, Pokéman, obscure facts about Machu Pichu, complex engineering of atomic structures, and a quote by Aristotle into one sentence; his fridge was covered in polaroid pictures, happy moments from his rich life. He was kind, hilarious, sensitive, sweet, a total bitch — nobody is perfect — and spending time with him left a lasting impression. He was interested and interesting. He was also depressed.

Earlier this year, his depression became unbearable. Unable to ask for help, obstructed by the black tarry pit that depression draws around you, like cold lava slowly pulling apart every facet of your life, every emotion — did you know Matt loved volcanoes? — he took his own life.

Because of the click-for-cash news culture we live in now, and because Matt was a photographer who took photographs of famous people (and they loved him for it), his death suddenly became public property. Would he have liked this, I thought, as I scrolled through the hashtag of his name that suddenly appeared, or would he have hated it. I couldn’t quite tell.

78% of suicides each year are men. Sweet boys, like Matt, who perhaps from the outside seem like they have everything — a penthouse flat he owned, a buff body, friends, a sense of humor, an amazing job that took him around the world, a beautiful cat — still can’t find the words to say how they feel. Men whose only answer to their pain is a very final solution to what can sometimes be a very temporary problem. You see, Matt was brought up in a Mormon family before leaving the church — the religion bans gay practice — he couldn’t find edification in the absurdity of praying away his problems. He literally did not know how to ask for help: suicide is the highest cause of death for young LGBT Mormons. Acknowledging you have a feeling, acting on it, talking about it, trying to fix it, imaging a life without the immense and pervading sensation that follows you around can become insurmountable. But it doesn’t have to be.

Who truly knows what a depressed person looks like? Matt was bubbly and engaged — but it was apparent no-one really knew how he truly felt, that on the other side of his sunny facade, just beyond his shoulders that heaved with laughter, there lay a very profound sadness. I hadn’t spoken to him for a while before he died. A few days before life became too much for his over-active, gentle mind, I walked past his flat and looked up to the window. I wish I had stopped and knocked on the door.

Grief is elasticated — you can get further away from a moment in time and suddenly be pinged right back there. Like all of his friends, when I am sent back to that place that reminds me of him, I don’t think of a depressed person. I won’t let it define him. I hope he has found whatever peace he needed. He left behind him an open letter to the world, but he couldn’t find the words to say to anyone how he really felt. What are we without love?

Please visit CALM for support regarding suicide and call Samaritans at 212-673-3000 if you need to talk.

Credits

Text Hanna Hanra