There was, at least, a small but important gesture of protest at this year’s Turner Prize. A few members of BBZ, enlisted to DJ at the opening last night, were wearing T-Shirts with “Black pain is not for profit” written across them. The T-Shirts were a reference to Luke Willis Thompson, a New Zealand-born artist whose work we could, at best, describe as “complicated”.

His works are almost portraits, shot on 35mm, they loop and loop on an old, clattering, noisy projector. His subjects are the relatives of victims of police violence. There was controversy when he was announced as being nominated for the Turner Prize — a similar controversy, on a much smaller scale, to that which engulfed Dana Schutz’s painting of Emmett Till at the Whitney Biennial last year. A controversy that neatly can be summed up by BBZ’s t-shirts: should we be making, or supporting, art made about the suffering of black people by non-black people. Should an artist be profiting from black pain?

The work in question is about Diamond Reynolds; the girlfriend of Philando Castile, whose shooting by police officers was live-streamed on Facebook. The work Luke has created of Diamond is, on the one hand, beautiful and affecting and moving, but it all comes from Diamond, who unfortunately becomes just a mute object of suffering. A telling moment comes in the film when we see Diamond’s lips move and no sounds come out. Just the continuing clattering noise of the projector. She’s silenced by his desire to create art.

And, bigger questions are here too, what can a work of art do that a live-streamed video of police shooting a man in front of his girlfriend and child can’t? Should you aestheticise trauma? Can a non African-American make work about this subject matter? Luke’s claim is that his work counters the spectacle of police violence, and yet you place this in a gallery, in Tate Britain, in the Turner Prize, and well it’s a spectacle (a different kind of spectacle, maybe).

The Turner Prize this year is all video and all politics, which provides easy comparisons with Luke’s work. Next to Forensic Architecture’s work on police violence in Israel, Luke’s political activism looks trite. Next to Charlotte Prodger’s moving and affecting film Bridgit, Luke’s cinematics of the body look one dimensional. Luke’s inclusion is a disappointing misstep after Lubaina Himid’s win last year, which felt like a massive victory for black British art.

And specifically compared to the work of Forensic Architecture, and seen in its shadow, Luke’s work just doesn’t work. Both look at police violence. The central problem of Luke’s work — how to turn injustice and suffering into art — is confronted by FA who simply present the shocking facts. Forensic Architecture’s work here is not wondering how to turn suffering into art but is asking instead: “What can art do to prevent suffering and stop injustice,” which seems a more important question at the moment.

Forensic Architecture look at the case of an Israeli police officer killing a Bedouin civilian. The police said he was a terrorist, and said that they shot him when he attempted to drive a truck at them. Forensic Architecture look at what happened and what the police say happened, reconstruct the events, uncover police lies, present them to the press, campaign for truth and justice. The Bedouin civilian, they reveal, wasn’t a terrorist and wasn’t driving a truck at them, and was murdered by the police.

It uses the techniques of the art film, the art exhibit, and the museum display to make these facts clear, make the truth more obvious, petition for justice. It provides an understanding of what happened, the lies provided by the police, how they countered them. There’s a timeline of facts and changing facts. But ultimately it ends with a sad coda of how – despite what they uncovered – no police officer was prosecuted for the shooting. Is it art? It doesn’t really seem to matter what art means in this context, simply that it can have an affect. Or try to have an affect. Provide a plan for action.

Naeem Mohamed films are aggressively long and obtusely political, at first feeling defiantly historical. To watch both of his works included, start to finish, would take a good three hours. Which is a good artistic statement. Good work demands time. Slowness. Thought. The most interesting work on display tracks a conference of the Non-Aligned Movement in 1973, a group of countries who aimed to sit outside the simple dichotomies of the Cold War. Naeem’s film reconstructs the posturing, lies, bravado, and manoeuvring of politicians at the time.

The same problems depressingly still persist, it seems to say. The same conflicts between spheres of influence, between poor and rich and developed and developing. Between east and west, left and right. Old disappointments, old dreams, old ideologies, reconstructed through a lens of today, contemporary interviews, contemporary politics. How far have we moved forward? How far have we come? Have we changed? It’s a big, complicated, unwieldy and interesting work.

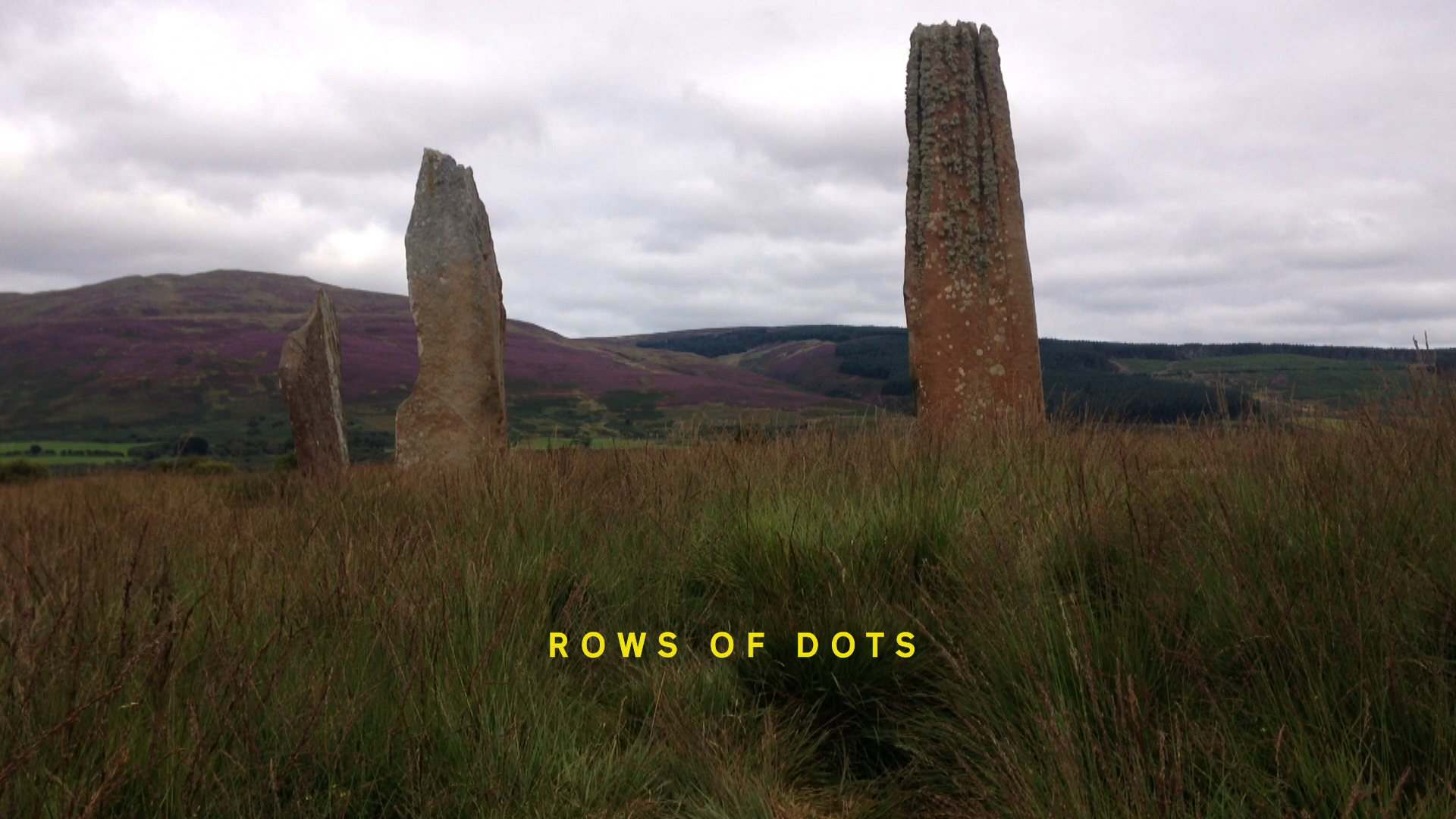

Amid all this sits the work of Charlotte Prodger. The mostly purely, wonderfully, beautiful work of art in the show. Her film, Bridgit, is intimate and poetic. Shot on an iPhone camera, it’s a simple series of landscapes — the sea, the countryside, domestic spaces — and narration culled from the artist’s diaries. It revels in its slowness and peacefulness. It takes its time. Hypotonic and gentle and domestic.

This drama of the quietness of domestic spaces, the sublimity of nature, stands out amongst these other masculine displays of Big Politics, Big Dramas, Big Events and Big History. But yet, for all that, it is still political. Nothing is more naturally political than the personal, and it is open with it; giving to the viewer, offering space and freedom rather than restriction. The slow movement of time in the video reflects the seeing of the eye, the Sebaldian narration its synthesis of history in the present.

The Turner this year is all about politics and video, obviously, but Charlotte’s film turns the themes and formats towards personal-ness and intimacy. It will, hopefully, overshadow the controversy surrounding Luke Willis Thompson’s film.

Interestingly I think, there’s a generational divide in the reaction to works like Luke’s. Frankly, millennials and gen z won’t really stand for bullshit artists aestheticising and profiting from black trauma. The beauty which Charlotte’s work offers seems more apt right now.