For much of the 70s, nightclubbing in Britain was a bleak affair: a stodge of surly bouncers, carpeted venues, crap drinks, and DJs cracking mom-in-law jokes before dropping The Birdy Song. When the punk movement brought iconoclasm, anger, and nihilism into the mainstream, it attacked this gruesome club culture as much as it did the pomposity of prog rock. For those kids who didn’t make it into a band by 1977, a seed of rebellion had been planted — one that would grow to fruition on the dancefloor during the 80s.

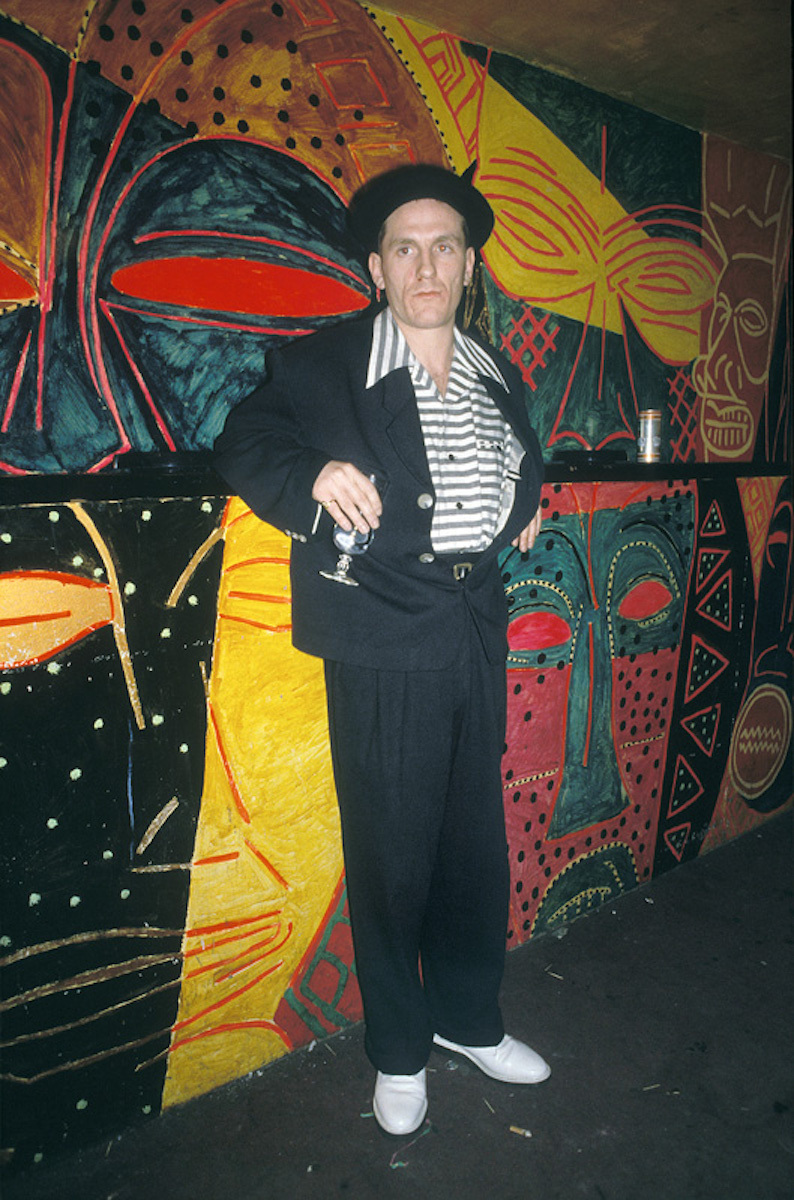

Chris Sullivan was one of those who started the 80s ready to take on the old guard. An incorrigibly flamboyant Welsh kid who’d grown up listening to the ska brought into Cardiff by Caribbean sailors, he’d moved to London to study art and fashion at St Martins, and had ended up a regular face at fellow Welshman Steve Strange’s club The Blitz. The Blitz has passed into legend as the place where London’s club scene truly kicked off — where dancing, drugs, cutting edge music and glamour collided into an alluring new bauble. Dancers twirled and posed to the detached sex music of the New Romantic scene; for a moment The Blitz was the centre of the world. However by 1982, the true innovators who had populated the club were bored and looking elsewhere — Sullivan amongst them.

Sullivan was sick of emotionally barren synthpop, and craved something with the warmth and soul of the ska records he had loved. He found himself drawn towards imported disco records, not the chart fodder of Motown or Atlantic, but underground soul, Latin, and jazz. After building up a rep with a few small events, he chanced across an opening at a venue on Soho’s Wardour Street, a place that had once been legendary 60s R&B joint Whiskey A-Go-Go. The heritage was too good to resist, and in October 1982 he opened the place, renamed it The Wag, and proceeded to merrily reshape club culture in Britain for the next 19 years.

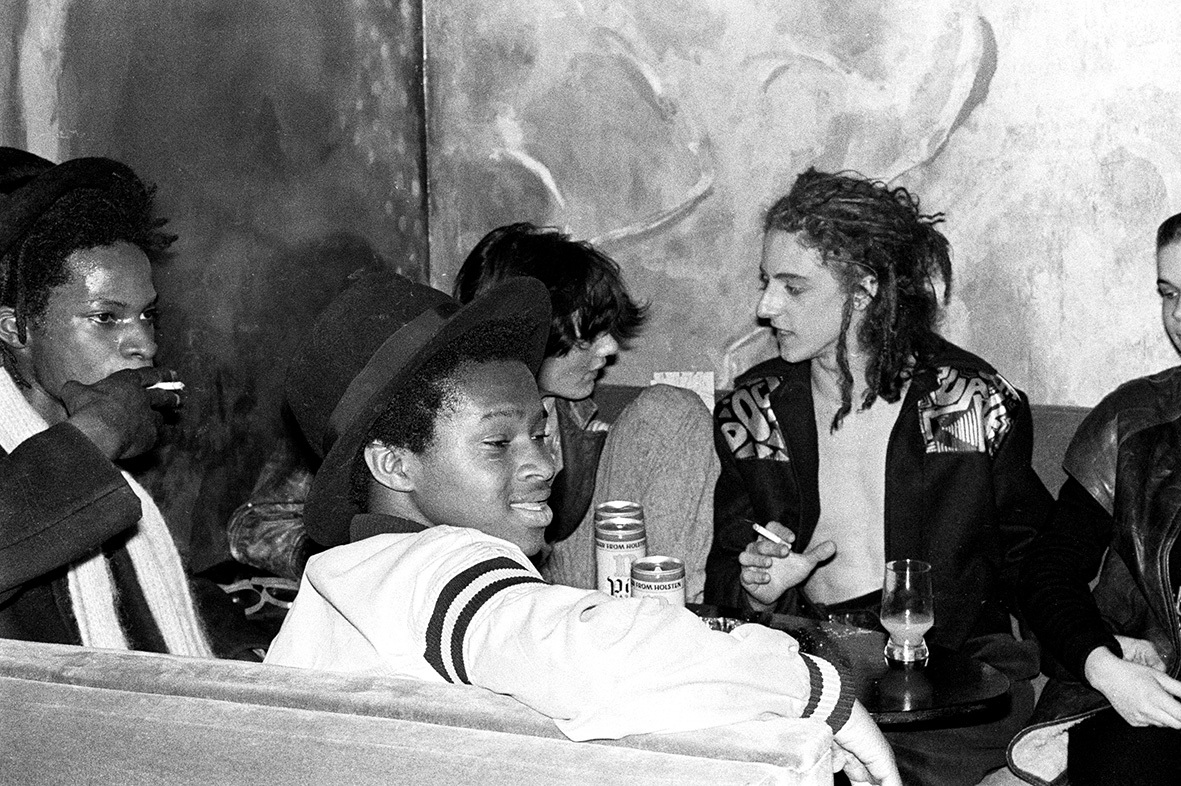

The Wag is famous for a number of reasons. The style pages were obsessed with it because, from the moment it opened, it was the place to go. Celebrities, divas, queers, and club kid fashionistas flocked to party on its hedonistic dancefloor. Everyone from David Bowie to Naomi Campbell passed through the doors. This alone wouldn’t be enough to warrant The Wag’s high standing in clubbing history; there have been hundreds of clubs lit up by the fleeting glow of glamour. Instead, The Wag’s legend was built by its remarkably forward-thinking music policy. Driven by Sullivan’s love of soul, the club became one of the first places in England to completely embrace first the hip hop, then the house explosions booming from New York (and all the fashion, slang, drugs, and music that came with each scene). The Wag’s clientele was obsessed with being on the cutting edge, and Sullivan recalls how this manifested itself in sudden sweeping changes in style that would go on to be mirrored around the country.

“The biggest change I ever saw was when we put on the Roxy Roadshow in 1982 — it had 25 different artists: Fab Five Freddy, Rammalzee, the Dubble Dutch girls, Futura 2000 doing live spray painting in the club. At the time New Romantic was so naff that everyone had gone back to wearing these 50s zoot suits. They turned up to see these artists from the Roxy Roadshow spinning on their heads and wearing tracksuits, and literally the next week everyone had dumped their 50s clothes and started turning up in Adidas tracksuits and baseball caps. I’ll never forget the headline in the Evening Standard was ‘a crimewave of Volkswagon and Mercedez Benz car badges has been stolen across the capital! Why is this?’ And that was because everyone was stealing the badges to wear, hehehe…”

Unsurprisingly, in a pre-internet world, the freshest threads weren’t always easy to get, and sometimes you just had to suffer to look good. “I remember Duffers of St George went over to America and bought a load of shelltoes and Gazelles and sold them when they had their market stall in Portebello,” says Sullivan, “but they’d only been able to get hold of left feet. So everyone had to buy pairs of left feet…”

From this point on, The Wag was fundamental to introducing hip hop to the UK. With few clubs supporting the sounds bursting from New York, The Wag picked up a reputation as the place to come hear — and in many cases see — the acts changing the face of music. The new hip hop fans found themselves rubbing shoulders with queer fashion kids, and everyone seemed to get along fine. “At the time it was as unusual to be in a tracksuit and breakdancing as it was to be dressed like Boy George. We were all outsiders.”

The club helped facilitate the good vibes with a strict door policy — people would probably call it creating a safe space now, Sullivan remembers it as a practical necessity designed to keep out the squaddies and stag parties roaming Soho looking to fight or pull, in whichever order. This door policy wasn’t without problems — The Wag was often criticized as being elitist, and there’s long been a story of New York hip hop pioneer KRS-One being turned away from the club on a night he was supposed to perform. This is a story Sullivan is keen to contextualize.

“KRS-One showed up with about seven of his huge mates and he called one of my Caribbean bouncers ‘an island n*****’. He’d tried to jump this big queue, the bouncers didn’t know who he was, so they stopped him, and he said ‘hey, fuck off island n*****.’ So they told him he couldn’t come in and I backed their decision, even though he was meant to play. I don’t care if you’re black or white, you’re not going to speak to my staff like that. It might have been alright for him to say that in New York to his mates, but it certainly wasn’t alright for him to say that to a Jamaican in London in the 80s. They didn’t take it well at all. No one’s ever told that story.”

This commitment to good vibes was aided by the club’s notoriously refreshed crowd. Over the years The Wag has gained a legend for hedonism that is probably way beyond the reality — but Sullivan points out that there was at least one genuine reason why the place became a place for inhibitions to be cast off like last seasons strides.

“Don’t forget ecstasy was legal in America until 1985, so for the first three years of The Wag, the place was awash with it. We had loads of Americans coming in, just bringing over bags of the stuff. It was how they’d pay for their trips to Europe. Jesus Christ, it was superb! Everyone was off their head, just dancing to this music.”

It’s little surprise that this positioned the club perfectly for the introduction of acid house. Chicago tracks were making it onto The Wag dancefloor by the mid 80s — a good few years before the 88 Second Summer of Love bought the scene into the mainstream. This was enabled by one of the resident DJs strokes of good fortune.

“Hector, who was our DJ on a Saturday night, had gone over to Chicago. He had links with Trax Records so he went over to their warehouse and was given a bunch of cassettes, so we had to install a cassette player in the DJ booth for him to play them — and they were really early takes on Jamie Principle, Marshall Jefferson — that was 85 or 86. Later we put on Love, a pure house night, and we had them all play: Tony Humphries, Larry Levan, Frankie Knuckles, Lil Louis, Todd Terry, every American who was big. But our bar take went from £2000 ($3000) on a night to £500 ($700), and our water sales went up by 5000% or something. It was all we were selling.”

The club finally closed its doors in 2001, exhausted after 19 years of late nights. Sullivan has just compiled the first of two box sets looking back at the history of the club, covering the period from 82-86. The mix of disco jams, rare groove and early hip hop sounds as likely to be heard in a club in Peckham or Dalston today as it was three decades ago, and Sullivan, ever keen to promote the underground, insists there’s plenty there that will appeal to a new generation: “There are big tunes on there everyone will know, but there’s a lot of excellent music people won’t have heard of on there. Mind you, not everyone’s as old as me.”

Stephen Linard

The Wag CD, four discs of remastered rare, classic and collectible funk, Latin, disco, hip hop and jazz that filled the floor, can be pre-ordered here. The Wag Launch Party takes place on June 18 at Westbank Gallery.

Credits

Text Ian McQauid