Two weeks ago “punk curator” Marc H. Miller ran into punk journalist Legs McNeil at the closing ceremony for an Arturo Vega exhibit at Howl! Happening in the East Village. He had almost finished putting together Hey! Ho! Let’s Go: Ramones and the Birth of Punk — his new Ramones exhibition at the Queens Museum — and was reminded of the time when Legs had scrawled his “punk manifesto” on a gallery wall in DC back in 78. “The idea of having someone write directly on the [museum] wall kind of stemmed from that,” Miller told us. “So when I saw Legs I said, ‘Hey!’ He went right for it — came out the next day and wrote ‘Pinhead’ on the wall, which is the perfect song for him.”

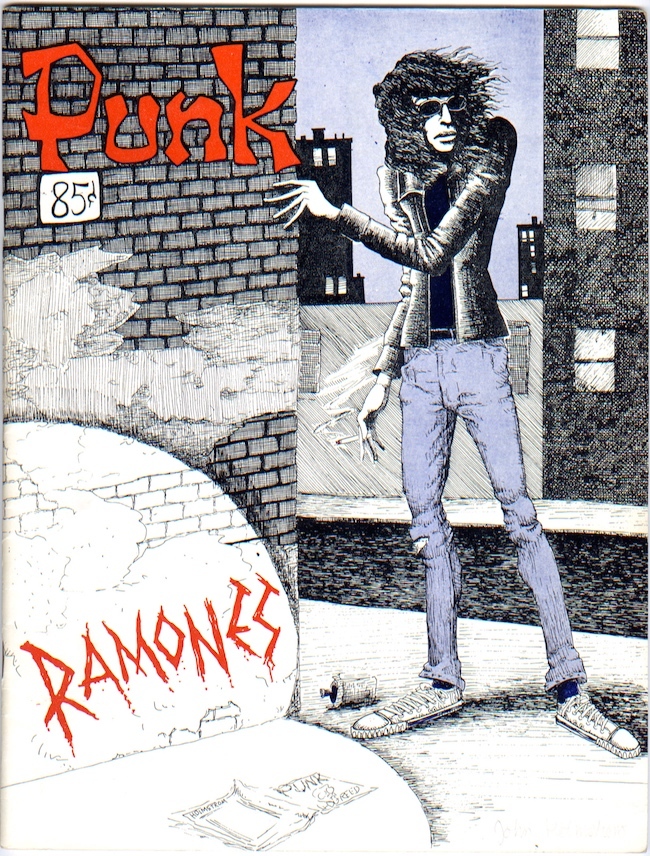

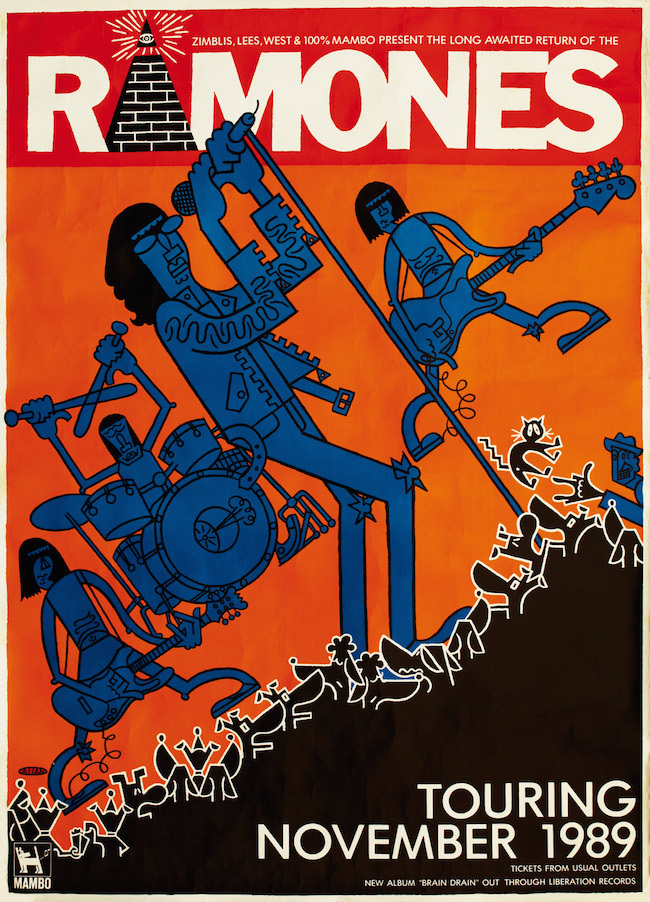

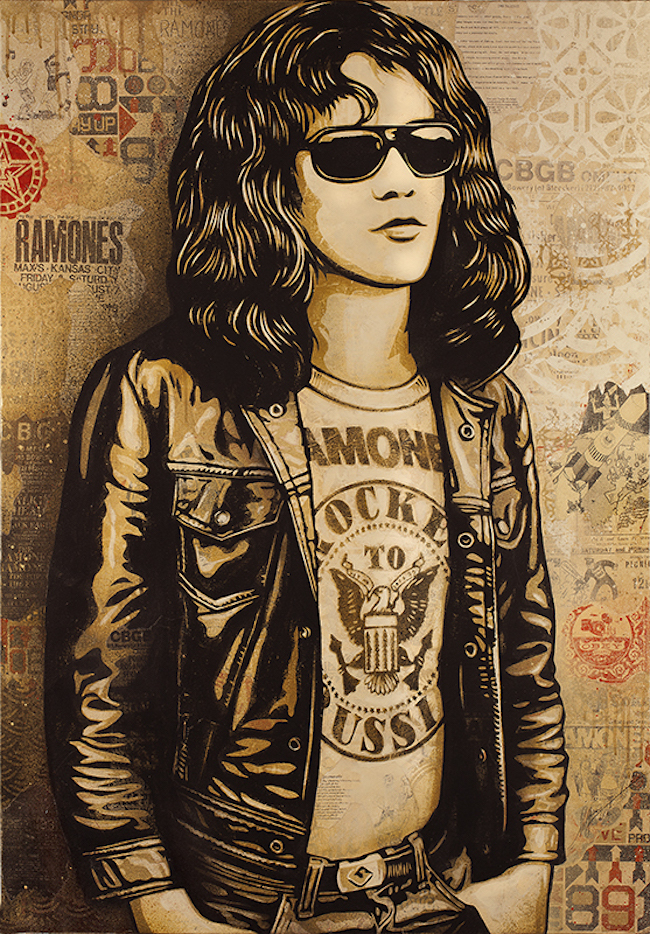

The iconic Ramones catchphrase “Gabba Gabba Hey” was the final flourish on an exhibition that Miller has spent three years mining his archives to create. Not that the material was ever far from reach. Miller’s personal punk archive site 98 Bowery takes its name from his old address near the original NYC punk club, which he frequented three or four nights a week as the Ramones were blowing up. And, crucially, as visual artists and photographers were throwing themselves into the melting pot of creatives increasingly bummed out by the pretentiousness of the art world at that time. Art and music were as inextricably connected in the 70s as they were in the era of Warhol’s Silver Factory, and Miller’s exhibition unscrambles all its various elements for a 2016 audience — Mark Kostabi’s digitally altered “Enasaurs” on a Ramones CD, a cartoon Joey on a 1976 issue of Punk magazine, portraits of the band by activist street artist Shepard Fairey. Woven throughout is a humorous commercialism seminal to the band’s explosion. If British punk was skeptical of mainstream acceptance, The Ramones were ravenous for it. We talked to Miller about the band’s Forest Hills beginnings and the visual artists seminal to their success.

What was your starting point for pulling together the exhibition?

From 1985 to 1991, I was the full-time curator at the Queens Museum. The last show I did with them was a very large and successful show on the jazz musician Louis Armstrong. He lived just a mile from the museum, in Corona. Then about three years ago I was visiting the museum. I started talking with the director, and said, “What about a Ramones exhibit?” In one second the director said, “Let’s do it!” The Ramones lived just a mile in the other direction — in Forest Hills — so in my mind Louis Armstrong and the Ramones are perfect parallels, which is really underscored by the fact that one of Joey Ramone’s last singles was “What a Wonderful World.” Then we started the odyssey of actually doing the exhibit, which of course entailed getting the permission of the Ramones’ management. They were a little reluctant at first, although they understood that we had the perfect venue, symbolically. They were the ones who got us to link the idea to the 40th anniversary and got us to collaborate with The Grammy Museum.

When did you first become aware of the importance of visuals and graphics to the early punk scene?

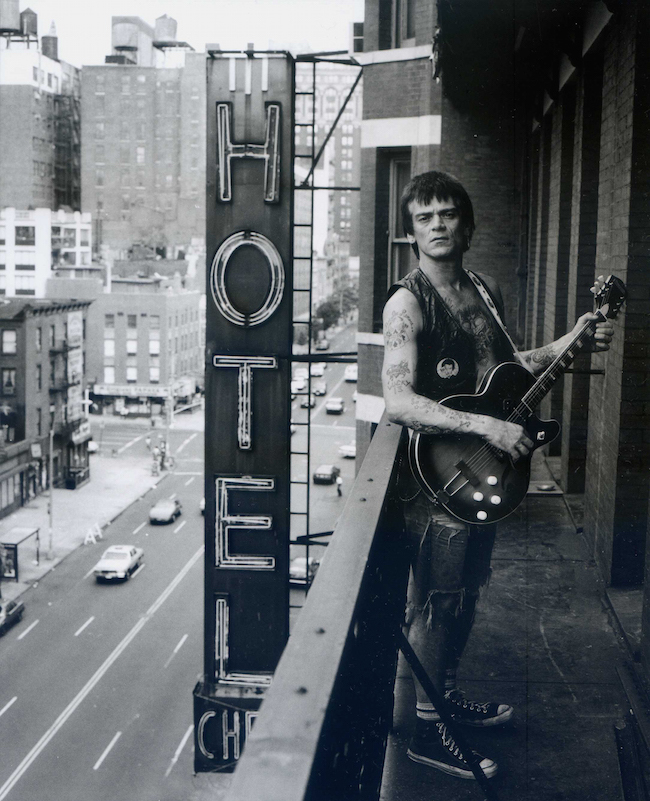

That was just the spirit of the early 70s. They’re almost perfect parallels — there were a bunch of musicians that were sick and tired of all the pretensions that rock had evolved into, and in the art world, there was a lot of pretentious conceptual art. Both the artists and the musicians were kind of excluded from the main commercial outlets. The 60s had generated so many musicians and so many artists that the galleries were stuffed and the record labels were stuffed, so there was kind of a DIY spirit that pervaded amongst the youth at that time. Everybody was looking for some action, and a large number of artists gravitated towards the music scene because it was much more satisfying to think in terms of posters and albums, or to take pictures for magazines and do drawings for fanzines. It was something that galvanized a lot of interest, and the Ramones were kind of the first off the starting gate. They personified the spirit so well through their look, the directness of their music, and their outrageous black humor. They were a real inspiration to everybody and they assembled around them a very strong contention of visual artists very early on — all of whom in their own way enhanced [the band’s] message or complemented their music and attitude, and are a part of their success.

How do you see the band’s upfront courtship of commercial success as interplaying with the anti-establishment character of punk?

I think they just took commercial success for granted when they started. They grew up with The Who, The Beatles, The Beach Boys, Phil Spector’s Wall of Sound — they were all great music fans, and they all wanted to be part of that history. But they made a few miscalculations! They miscalculated the resistance. That first record, they were acting like psychopaths. It took a while for people to realize that it was kind of funny, and that it really wasn’t that threatening. Like any group signed to any record label, the label was putting some pressure on them to get more commercial. There’s a press release from those years saying, “Don’t call it punk — call it new wave.” That was part of this attempt to make them more commercial, and they made some compromises. They started with the photos — instead of standing against the brick walls of the Lower East Side slums, glaring at the camera, they started using John Holmstrom’s cartoons on their albums to lighten them up a little. In the exhibition, it’s about the cover. “Take off the leather jackets, that’s why we’re not selling!” So we have the two photos by Mick Rock, one of them with leather jackets and one without, and they went with the one without. We actually have the red T-shirt that Johnny wears on that cover, looking completely innocuous and out of place!

Was there a conflicting perspective regarding punk and commercialization in Britain vs in America?

Kind of. Although I’m not so sure it holds up any better in England than it does in America. Every performing artist has their core, and they’re not going to stray too far from their core. Maybe what you’re saying is that there’s some kind of ideology that rules around punk that’s being imposed on the artist and maybe trying to take on that ideology might be more of a compromise than anything else.

It reminds me of Vivienne Westwood’s son threatening to burn all his merch to protest the commercialization of punk in light of these 40th anniversary events.

Right, and of course his father would have been totally against commercializing anything, but he takes after his father as far as hyping things! I’m just joking, but his father was a great commercializer through hyping things. I have no knowledge of the son, but I understand he has a very successful clothing business. I only learned that because he’s threatened to burn all his memorabilia! So he’s doing something right. And the name of the brand is perfect for this gesture. But punk was, in a lot of ways, about hype.

In New York, you had a club — CBGB — that had three acts a night. Going through hundreds of groups a week, or a month, and they’re all different. The difference between Talking Heads and the Ramones and Patti Smith — you could go on — was tremendous. But it was clear that something was happening there, and everybody was talking about it. It was like a whole new generation suddenly getting the stage, and all the journalists start coming in and using the term punk — which had been floating around, but its hold was cemented by Punk magazine. John Holmstrom and Legs McNeil were at CBGB almost every night, and that magazine was pretty much a house organ for CBGB. Then suddenly the term moved across to England — there were probably people who used it there before, just like there were people in America that used it — then it kind of comes back with all that publicity surrounding the Sex Pistols.

Going back to what you were saying before about fashion, and the Ramones’ very simple but very iconic look — do you think their way of dress was as vital to defining punk as art was?

Yeah, defining something. This was the era of glam. In that demo set that we found, there’s one of the earliest pictures of the Ramones. Johnny is in some kind of silver pants, and Dee Dee has on what looks like a woman’s scarf. That’s the background. Then they decided, “We’re just going to dress the way we dress.” They just decided to react against the costuming that was going on at the time. They brought to the stage some pretty astounding things. Not so much the leather jackets, which are a pretty stock item, but the graphic T-shirts.

In the early 70s, T-shirts were still an undergarment, and the only ones you could really buy were white T-shirts. What they got was a patent with these advertising T-shirts. That was something that companies would do — producing T-shirts with their company logo on it. It was kind of a form of pop art, in most instances they were being given away. You couldn’t go buy them. It sounds almost ridiculous to give [the band] credit for wearing decorated T-shirts, but they made it a big statement. Their art director Arturo Vega helped design their logo, and when the band went on the road and the band didn’t have any money to pay him, he said, “I’ll just make some T-shirts and sell them.” That turned out to be remarkably successful, and we’re talking about an era when there was really very little in the way of rock merchandising. The biggest rock merchandising happening was around The Monkees, which was really a T.V. show.

You previously likened the roots, attitude, and social connections of punk art to what was being called feminist art at the time. Can you elaborate on that?

It was getting away from the intellectual pretensions of the time. At that time it was art about art, and in music it was art about virtuosity. Both art and music are containers for expressing something that should be important to the creator, and that began to reassert itself in the early 70s. The women of the feminist art movement had a lot of things they wanted to get out there, and kids also had a lot of things they wanted to get out there — their world, and their passions, and their thoughts. So they were very parallel, though the messages were different. They’re two sides of the same coin. We did a show in Amsterdam in 1979 and it was reviewed by a feminist art critic who called it “macho art.” At that point it included Robert Mapplethorpe, and a lot of the aggression of punk struck at least one critic as the opposite side of the coin but not a friendly one! Of course a lot of what we were showing was to do with his connections with Patti Smith — he was just another one of the visual artists who linked himself to the music world.

Hey! Ho! Let’s Go: Ramones and the Birth of Punkis on display at Queens Museum from April 10 –

Credits

Text Hannah Ongley

Images courtesy of Queens Museum