At the time of writing, the Instagram hashtag #instaart has a stunning 13,843,454 posts (#artporn, 286,763), many of which accompany images from Art Basel in Switzerland, which opened to the public today.

You’ve read it, I’ve read it: social media is profoundly changing culture. But wandering around the Frieze Art Fair in New York last month (and simultaneously looking at images of the very same works on my phone), it was impossible to ignore the Instagram explosion that art fairs have recently become.

So, what is the impact of the ubiquitous photo-sharing platform on the art world — a community so exclusive it gives the fashion industry a run for its proverbial money? Is Instagram actually making the art world more democratic? Will the rise of the #artselfie affect which works we actually see on display?

Fashion, now, has reality shows. There are documentaries about the inner workings of Vogue and the Met Ball. Balenciaga, Prada, and Marc Jacobs stream their runway shows in real time. But the art world remains more mysterious, driven by colorful but less-easy-to-market personalities: artists with IDGAF attitudes, and a partially anonymous group of collectors and members of the 0.1 percent.And yet, Instagram, which has rapidly become the fifth most popular social network — and a near-necessity for nearly every creative person — is fostering an unprecedented era of inclusivity between the general public and the industry.

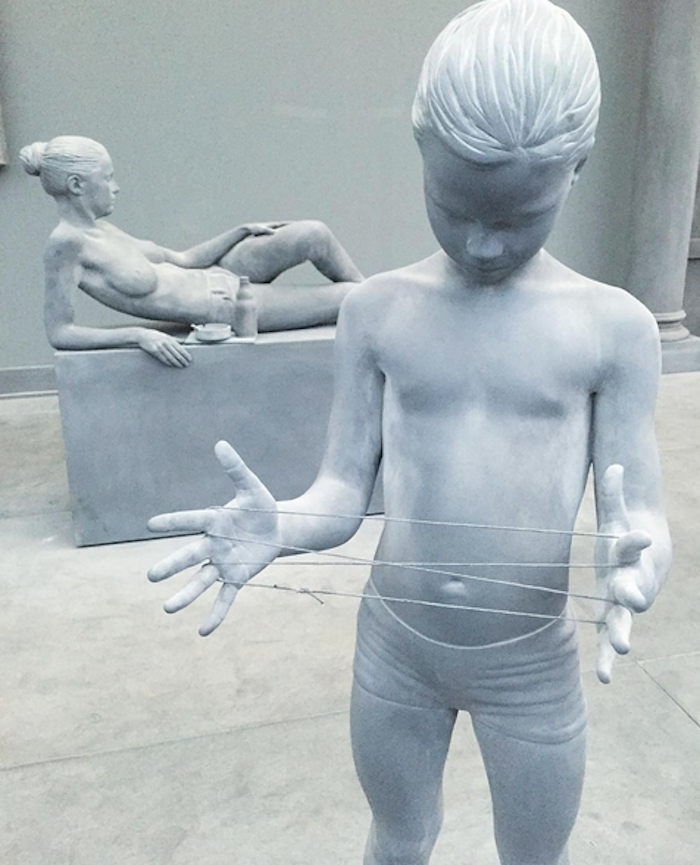

Days before Art Basel’s public opening, a small group of collectors and institution staff descended on the fair for the VIP viewing. Through their Instagram posts, this cohort provided a first look at the art on display, giving followers — many of whom will not attend the fair themselves — an intimate sneak peek. So far, Hans Op de Beeck’s The Collector’s House, an immersive set of rooms in grey plaster, has been a popular photo subject. (How could it not be, with its full-scale libraries, Romanesque sculptures, and lotus ponds, all rendered in Pompeii-like ashy hues?) Other VIPs have posed in front of Udo Rondinone’s rainbow sculpture, or Jeppe Hein’s mirrored balloons, which seem to actively invite selfies.

Among the factors that make a work of art particularly Instagrammable: a strong use of color; some interactive or tactile element; an instantly recognizable and cheeky or politically relevant idea. (If you’re Tracey Emin, your work has all three.) In essence, works that perform well on social media must have enough of a presence to jump off a small smartphone screen and be shareable enough to become a fleeting form of cultural currency.

Consider the Japanese artist Yayoi Kusama. At age 87, Kusama has been making art since the early 50s and her unique psychedelic, Surrealist-Pop sensibilities — not to mention her several major shows in the past five years — have made her one of the most Instagrammable artists in the world. Her work The Moment of Regeneration was a standout at the Frieze booth of Victoria Miro, who is also displaying Kusama’s work at Basel. (Her pumpkins are also on show at Philip Johnson’s Glass House in Connecticut, which caused a sensation on this writer’s Snapchat feed.)

Kusama’s work has a trippy, through-the-looking-glass aesthetic that easily translates into impactful photographs. In 2013, her Infinity Mirrored Room — The Souls of Millions of Light Years Away, at David Zwirner’s Chelsea location, rocked the art world and Instagram alike. The mirror-lined room, adorned with vibrating colored LED bulbs, was the perfect space for a selfie. Julia Joern, a partner, as well as the director of marketing, publications and press, at David Zwirner, tells me: “[The show] was a huge tipping point, and it was completely unplanned. But it proves the power of social media.” Lines to enter the show reached up to three hours long. There were also four marriage proposals in the room, Joern says.

Is there a downside to the work’s explosion on Instagram? “For the Infinity Room, I think there’s some sense of ‘I’ve seen it already because I’ve seen it on social media, so I don’t need to go,'” says Joern. “[But] nothing will ever change the physical encounter with a work of art and the feeling you get in terms of scale and your own sensory experiences.”

Cory Nomura, director at Andrea Rosen Gallery in New York, puts it similarly: “Instagram can create a false sense that you have experienced a show when you haven’t, which is a critical problem with the kind of ubiquity of Instagram, [but] I still think there’s a kind of tradeoff that you’re making — it’s better to see something rather than nothing.”

Likewise, Elisabeth Sherman, curator at the Whitney, says, “For every instance of someone saying they’ve already seen [a work] via Instagram, there are probably more instances of people who have learned about things and become excited about them, and therefore make the effort to go see them because of Instagram. So I don’t feel like it’s keeping people at home — rather, it’s changing the visibility of things.”

There is also a sense that the popularity of large-scale interactive works like Hans Op de Beeck’s and Kusama’s — as well as shows like James Turrell’s recent Guggenheim retrospective, the Rain Room at MoMA, and Kara Walker’s A Subtlety at the Domino Sugar Factory — are growing proportionally to our dependance on photo sharing apps. As Charlotte Cotton, a writer and curator-in-residence at the International Center for Photography, tells me, “The reaction to social media is really [promoting] a super pronounced expectation of physical space, what it means to be in the presence of an artistic idea, and a strong confrontation of the bodily.”

“Instagram is not visually democratic,” says Brooklyn-based artist Rachel Libeskind, whose mediums include painting and performance. “It favors 2D works and photography, while installation, performance, and any works that exists in a 3D context are much, much, harder to ‘market’ through [the] platform.”

Cotton has an interesting take on these developments, suggesting that museums haven’t quite become digitally fluent: “I think [art] institutions are kind of still run and operated by people in the analog world who are doing kind of clunky and strange things with [social media], because they’re not digital natives. It’s going to be a really exciting to see where museums and institutions are in ten years.”

Artists, too, feel the pull of social media in their creative practice. “Instagram has become a Frankenstein, in which you cannot escape feeling pressured to conform to the grid…this kind of homogenization of aesthetic is super dangerous to any artists, anywhere,” Libeskind says. But do galleries and museums consciously organize shows to cater to this Instagram-obsessed landscape?

I asked several art professionals about whether the large amount of mirrored pieces I noticed both at Basel and Frieze was a nod to the selfie-obsessed masses, and the answer was a loud “no,” mirrors have been an important part of art history since well before the advent of the iPhone. Or, as Zwirner’s Julia Joern puts it, “There’s no feeling that we should put these shiny Kusama pumpkins out because it will be a social media sensation, it’s just that shiny materials are really popular in contemporary art.”

If connectedness is the fundamental drive behind our use of social media, posting images of art seems both natural and like a valuable opportunity for education and inclusivity. The “been there, done that” effect may just be a small price to pay for more transparency and even democratization. So when you post that art selfie at the new Tate Modern, don’t forget the hashtag.

Credits

Text Emily Barasch