In recent years, embroidery has undergone a significant image overhaul. Traditionally viewed as a domestic chore, a hobby, or most contentiously a “craft,” we’ve seen it be liberated from this historic setting while remaining firmly in the world of women.Young female artists are increasingly embracing it as a platform for expression and cultural commentary. Drawing on its heritage and struggle to be taken seriously as “high art,” it’s not surprising their work largely centres on sex, gender and our tendency to dismiss activities seen as “female pursuits.”

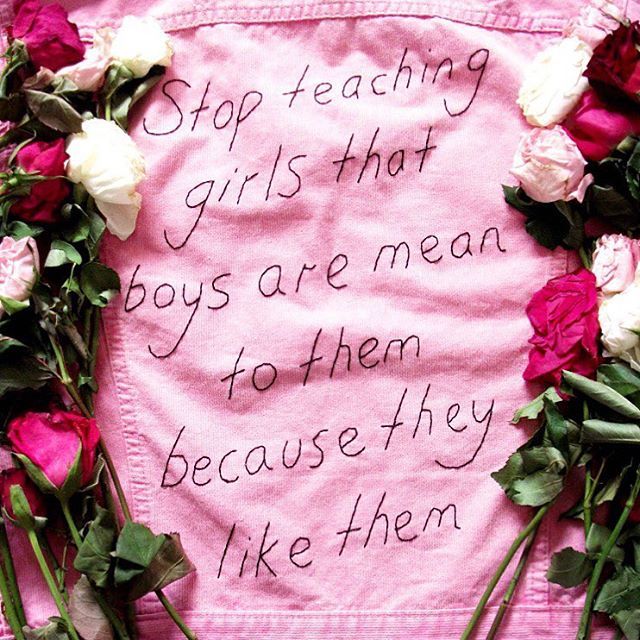

“When I first started embroidering, it was seen as more of a craft…regarded as something that you don’t need any creative skill to do,” explains Sophie King, the brain and fingers behind King Sophie’s World. Her luxury custom hand embroidered sequin patches appear everyone from glossy magazines to Gwen Stefani’s clothes, but her most ardent following has been through Instagram. There images of her feminist garments and accessories are fawned over and shared constantly. Maybe you haven’t heard of King Sophie’s World, but chances are you’ve seen her embroidered piece reading “Stop teaching girls that boys are mean to them because they like them” doing the rounds.

Speaking to i-D she reflects that while historically embroidery has been seen as “women’s work,” over the past year or so she’s noticed that starting to change. “It’s been described more often as art and there’s been a greater appreciation for the skill that goes into it.”

Despite the fact that tapestries have been celebrated as artistic and cultural treasures for centuries, we’ve failed to see embroidery exalted in the same way painting or sculpture is. Sophie continues, “During the Italian Renaissance craft was elevated to art as we know it today, yet embroidery was excluded and remained so from the canon of art history until very recently.” She largely credits that recent shift to Instagram, “With technology and the internet, we no longer need to rely on these old power structures to get our voices heard.”

This is obviously not new, Tracey Emin’s textile works have been toying with notions of acceptable femininity for decades. While Ghada Amer has made a career of using a combination of painting and needlework to challenge entrenched ideas of masculinity, sexuality and postcolonial identities in art. More recently Heather Marie Scholl has examined the interplay of female history, race and white supremacy in her delicate series Whitework, and her own experiences of gender in an ongoing project of self portraits.

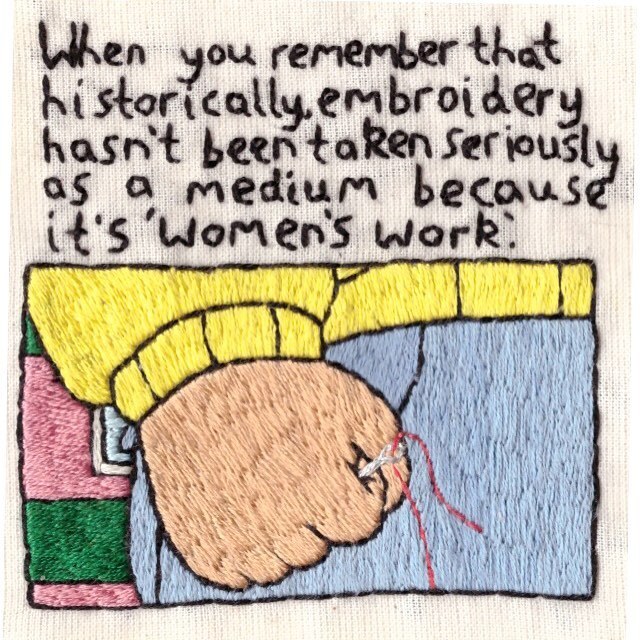

But the discussion seemed to officially take it’s place among fourth-wave online feminist culture a few weeks ago, when Hannah Hill posted what might be the first piece of viral embroidery. Well, at least since the The Bayeux Tapestry blew up in the 1070s. Chances are if you clicked on this article you’re probably familiar with the her stitched meme of everyone’s favourite aardvark Arthur clutching a needle and thread with the text: “When you remember that historically, embroidery hasn’t been taken seriously as a medium because it’s ‘women’s work'”. You couldn’t ask for a more complete encapsulation of the practice’s growing place in pop and art culture.

The piece took the conversation off Instagram and into the wider media, picked up by countless websites it undoubtedly introduced the politics of needlework to a fresh audience. Looking at the huge response to her work Hannah also credits the internet as the primary force changing people’s opinions of needlework: “With social media, artists who work in textiles, specifically embroidery, can meet like minded people and develop followings which in turn change peoples minds about the medium, purely based on exposure to it.”

Personally she always recognised the innate connection between embroidery and feminism, and her engagement with the two grew together. She was interested in the way that long before Instagram, women were already using the medium to critique social, cultural and political issues and tell their own stories. Prior to Tracey Emin even thinking of embroidering the names of everyone she had ever slept with onto the walls of a tent, women were communicating through their work.

Victorian ladies regularly used coded flower symbolism in their pieces. Isolated and muted in their domestic spheres, embroidery offered a form of silent expression. The practice was said to be inspired by tales of medieval chivalry, where women would communicate with their lovers through coded pieces of embroidery.

From that perspective, the new generation of embroiderers aren’t really that far away from their foremothers — they’re just talking louder and finally getting some credit. “I feel empowered to be able to make art using embroidery,” Hannah continues, “because in the past it has been pushed aside as a medium only for housewives to have as a hobby behind closed doors, lacking in creativity or skill.” But while she’s grateful for the audience and opportunity available to her, she still aches over the fact textiles has been dismissed for so long.

Credits

Text Wendy Syfret