You’ll find one of Nan Goldin’s most famous photographs mounted in Boston on Saturday, when the Museum of Fine Arts opens its new photography exhibition, (un)expected families. That fact alone isn’t so newsworthy. (Goldin has had a busy year. She’s shown at MoMA, the Portland Museum of Art, the Irish Museum of Modern Art, and twice at Matthew Marks Gallery over the past 12 months). But, among these thousands of Goldins, this one photograph feels special.

(Un)expected families considers how we define, and photograph, our families. Culled principally from the MFA’s holdings, the exhibition’s 80 pictures were made over 150 years by pioneering photographers including Gordon Parks, Diane Arbus, Sally Mann, Bruce Davidson, Tina Barney, and Dawoud Bey, as well as New England-area artists.

The show features fine art images, social documentary work, and vernacular snapshots from family albums and school yearbooks. It’s organized around three broad types of families: generational blood relations, romantic unions, and “the chosen family,” Karen Haas, the MFA’s Lane Curator of Photographs, tells me.

Goldin’s inclusion is bang-on. “We think of her as Boston’s own great photographer,” says Haas. Goldin emerged from the School of the Museum of Fine Arts in the mid-1970s and became perhaps the most important chronicler of the chosen family ever. Her Ballad of Sexual Dependency (a series of snapshot slideshows that became an iconic fine-art book) is generation-defining.

Goldin first found, and captured, her tribe in Boston. Her earliest black-and-white photographs were made at The Other Side, the first nightclub in Boston to allow same-sex dancing, and a hub for local drag queens. Over the following decades, Goldin obsessively documented her chosen family of friends, lovers, queens, and queer folks. One of the pack, she captured her community as beautifully as she saw it, even in moments of unimaginable sorrow and death.

Ahead of the exhibition’s opening, I asked Haas to discuss five photographs (by Goldin, Tina Barney, Milton Rogovin, Dawoud Bey, and Consuelo Kanaga) and their place within the MFA’s big, beautiful family.

Nan Goldin, Jimmy Paulette and Tabboo! in the bathroom NYC, 1991

“What we often talk about when we talk about Nan Goldin is the idea of her chosen, adopted family. The connection is so palpable and powerful. You feel it between the subjects, and you feel how much she admires her friends. It’s a beautiful, sympathetic, sensitive picture. There’s a quote of hers I used on the label, one I’ve always loved: ‘I used to think that I could never lose anyone if I photographed them enough. In fact, my pictures show me how much I’ve lost.’ I still get choked up. It makes me think of the power of photographs to hold on to something, that talisman-like quality.

In the digital age, we’re constantly immersed in photography, but it has this ephemeral quality. It’s all in the ether, all on our phones. It feels very fragile. We, as curators, are struck by the fact that so many professional photographers are making photographs of family. Might that have to do with that fragile nature of so many of the images of our loved ones, the people we care about? I became really interested in this idea of the photograph as talisman — an object that has power as a kind of reliquary. It holds all these feelings, all these emotions.”

Tina Barney, Thanksgiving, 1992

“This is one of our major works by Tina Barney, who’s based in Rhode Island. This is her own close-knit circle, and it’s relatively early work. This was done before The Europeans, and there [seems to be] a natural ease to the picture. It seems she’s very much at home there, literally. I think there will be interesting conversations about if it’s staged, or a completely natural scene.

In a number of instances in the show, I’ve created groups of photographs that speak to the loci, or centers, of family life. The family car, for example. This photograph is on a wall that’s all about the kitchen table. On that wall, we have Lewis Hine’s family of workers — a social documentary image — and Bruce Davidson’s Harlem families. On the same wall, I have Carrie Mae Weems images from The Kitchen Table series. I wanted to inspire people to look at the differences in motivations between someone like a Lewis Hine, a Tina Barney, and a Carrie Mae Weems. How things like color, scale, and documentary impulse inform each one.”

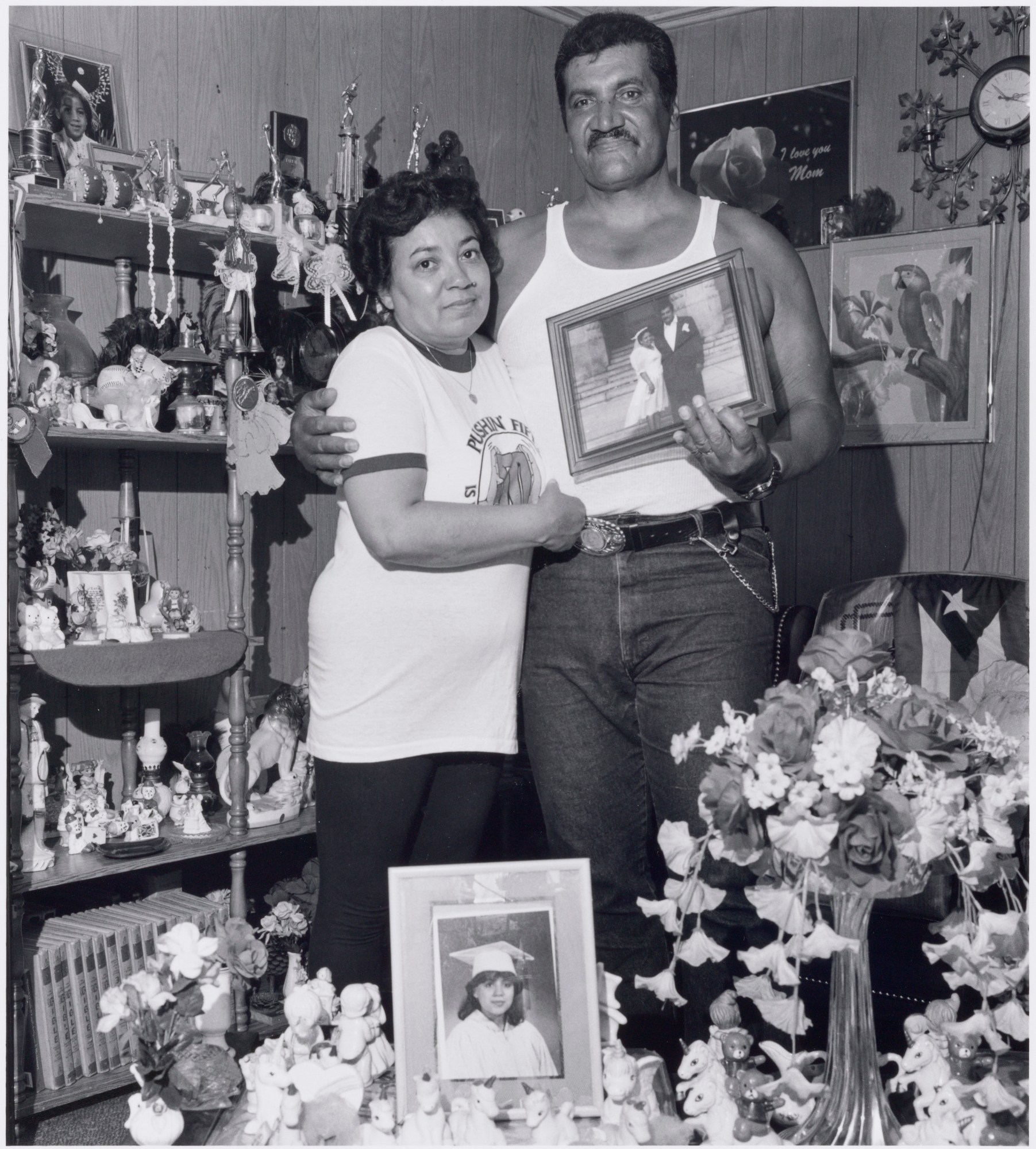

Milton Rogovin, Felix and his Wife, Buffalo, 1992

“Milton Rogovin worked in Buffalo, NY for his entire career. He made these amazing photographs of people in their homes and workplaces. We have a large collection of his work, and two photographs will appear in the show. In both cases, his subjects hold up their own portraits of themselves, wedding portraits. What I love about the picture is the obvious pride. There’s something really beautiful about Felix and his wife standing up together and holding their picture, surrounded by all the wonderful tchotchkes that make up a life. There’s a richness in this image.

The work is featured in a section of the exhibition that’s all about the role of family photographs in our telling of our own stories. We’ve included work by a local artist named Caleb Cole, who combs through flea markets and collects family photographs that have been untethered from albums. In each [photograph], he identifies the one person in the group who feels as though they are the odd person out. He digitally “whites out” everyone else in the image and re-photographs it. Another artist, Justin Kimball, has made a picture of an empty basement. You see a family photograph on a dusty table, but with a gun and a Christmas tin — all that’s left behind after someone’s moved from a house, and how photographs live on.”

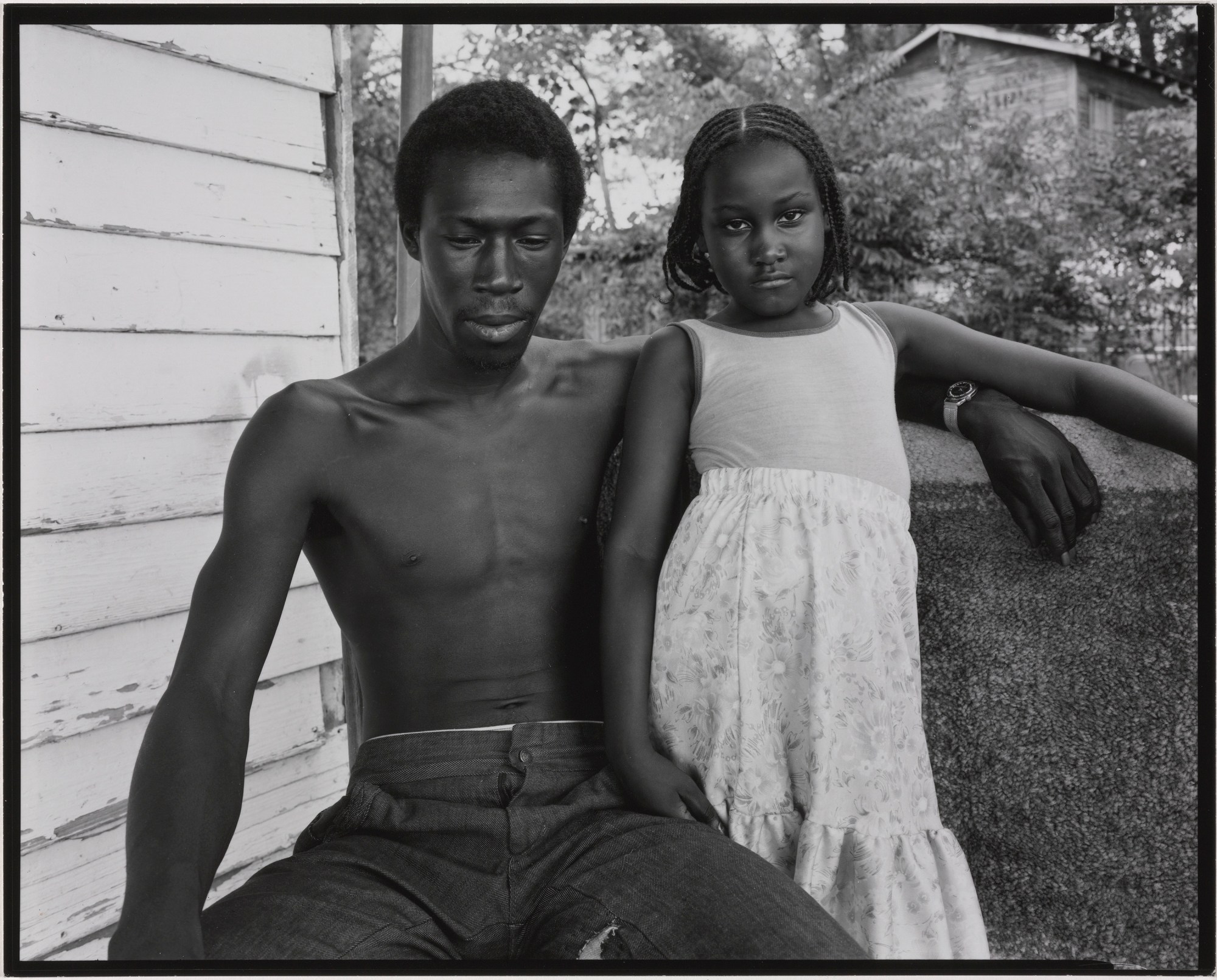

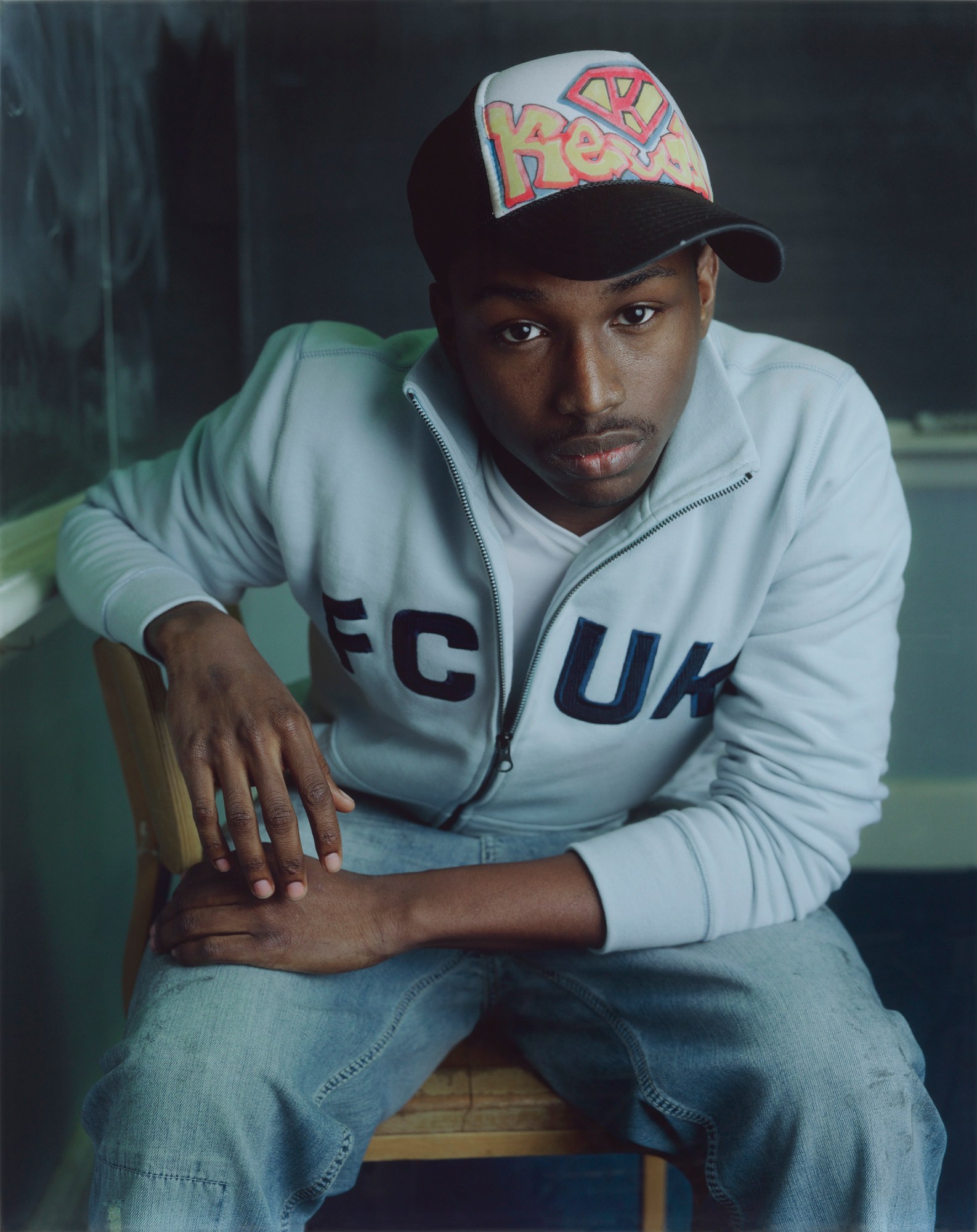

Dawoud Bey, Kevin, 2005

“The Dawoud Bey is — I hate to admit — maybe my favorite photograph in the show. It’s a picture I first saw in 2007 at an exhibition at Phillips Academy in Andover. Each image in the Class Pictures series has a text that goes along with it. Kevin’s is just amazing. He talks about the death of his incarcerated father, and his mother’s depression — how these things forced him to become self-reliant. He says it’s the best and worst thing that’s ever happened to him. And what’s interesting: Dawoud said to me that this young man is the only person of that Class Pictures series he’s reconnected with and rephotographed later. They crossed paths when Kevin was in college at Emory University.

To be honest, I was tempted to leave the high school experience out of the show. But, as we were talking about with Nan Goldin, if you feel distanced from your family when you’re young, you create some incredibly strong families for yourself. You make a circle that gets you through. I think that’s an interesting thing to represent. One of the pictures in the show is by Zoe Perry-Wood, who photographs the BAGLY [Boston Alliance of Lesbian Gay Bisexual Transgender Queer Youth] prom every year. The picture in our show is of these two young men proudly standing up together.”

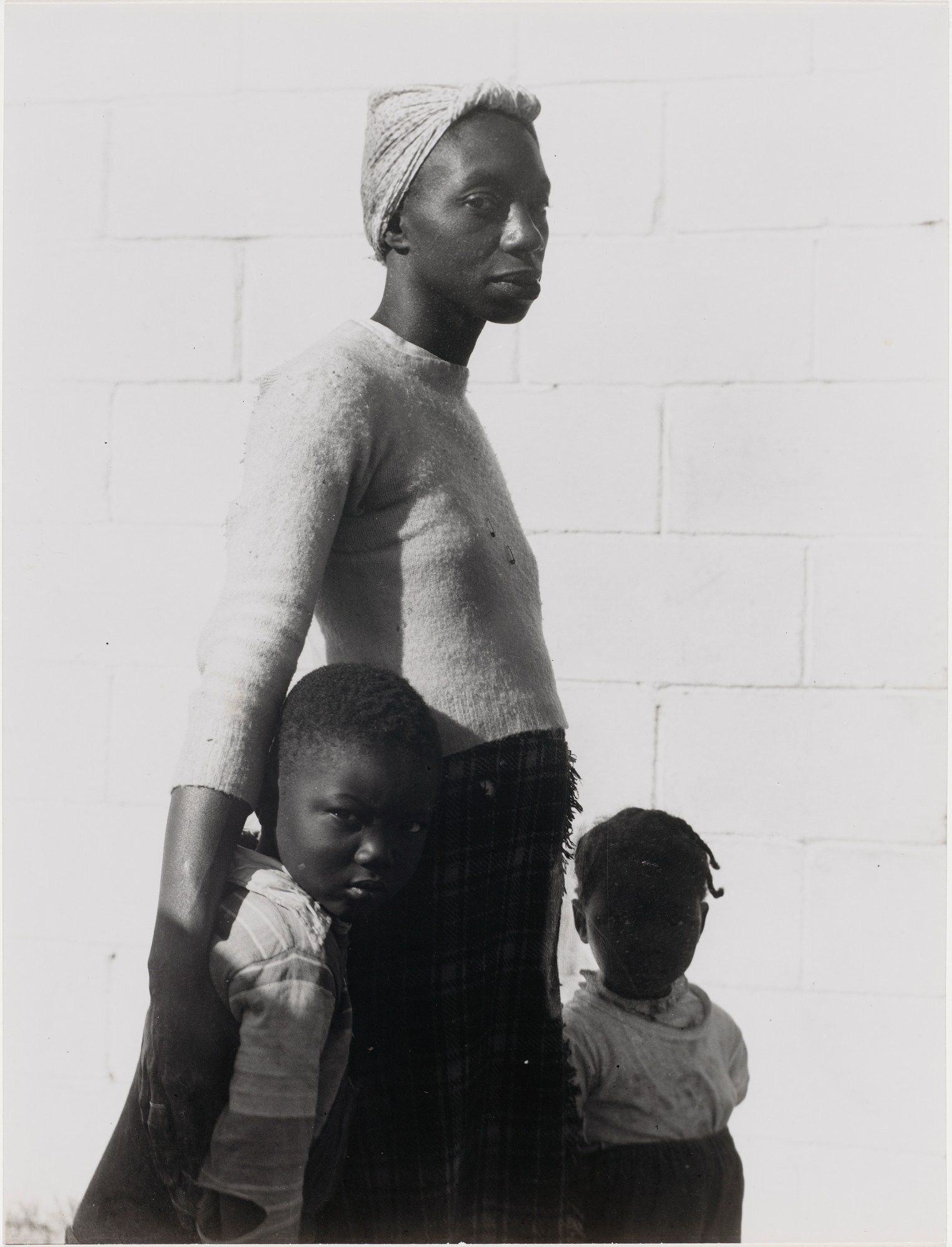

Consuelo Kanaga, She is a Tree of Life to Them, 1950

“For a long time, Consuelo Kanaga was sort of under the photo history radar. She’s a powerful photographer, but relatively unknown; her focus is on the lives of African Americans and issues of social justice. This was her most famous picture, and it was included in The Family of Man show, a somewhat controversial exhibition. [The subject] really is such a strong anchor, and yet so painfully thin. The children are literally hanging on her. They are holding her, she is holding them, and they become one. I love the way their bodies merge.

We’re hanging this work on a wall of all generational families — mothers, daughters, sons, siblings. This picture will be next to a wall of “Hidden Mothers” from the Victorian period, and a photograph by Nick Nixon of a mother carrying a picture of a baby to a funeral. In these cases, it’s this idea of the mother’s body as protective. I’m really interested in how, when people photograph family members, there is a sense of embracing, lifting up, or literally enveloping the other. It’s fascinating.”

‘(un)expected families’ is on view at the Museum of Fine Arts Boston from December 9, 2017 to June 18, 2018. More information here.