As you may have noticed from all the op-eds that have been written on the topic lately, London has become too oppressively expensive to maintain a dignified existence. Many of those just barely clinging onto a dingy shared flat in some commuter belt purgatory like Brockley feel pushed into making a decision: wade further into the urban overspill, perhaps even into the provincial hinterland beyond the city’s limits, or maintain a cosmopolitan lifestyle by relocating to an urban center elsewhere in Europe.

For many that choose the latter — particularly the young, mobile, creative, and free — Berlin seems to be the default destination. It’s easy to see the appeal of the German capital to a beleaguered Londoner; in terms of nightlife, culture, and urban scale, it’s the closest substitute that the continent has to offer, and it comes at a significantly lower price tag. Sure, Paris might be a more accurate like-for-like comparison, and Athens might be cheaper, but Berlin offers a happy medium: all the cultural familiarity of northern Europe, minus the suffocating financial pressures.

This familiarity gives many people the mistaken impression that the German capital is simply a more bohemian version of London, where rents are still affordable and the cost of living is cheaper (68% and 47% lower, on average, according to Numbeo’s cost of living calculator). It’s a city that gets romanticized to the point of myth by its admirers, but this pathological idealization distorts the reality.

Berlin’s fabled rent prices, for example, might be low, but you’ll subsidize every Euro you save in anxiety and frustration as you attempt to navigate the convoluted local rental market. Most people here sublet, and seeing as everyone wants to live in the same five areas in a city that welcomed 45,000 new arrivals in 2014 alone (the 10th year in a row that its population has grown by this sort of proportion), competition is relentless, with one subletter telling me that he received some 70 or 80 enquiries when he listed his spare room. Having just moved to Berlin as well, my anecdotal evidence suggests that this isn’t some sort of freak outlier either.

Finding somewhere to live in Berlin is a lot like looking for a job: you join one of the many dedicated sites or Facebook groups, wait for someone to list a room, then type out a personal cover letter explaining why you’d make a great flatmate — how you’re spotlessly clean and outgoing and bake cakes obsessively but never eat them, so would like to live with someone who will. If you stand out, you’re invited around to meet your prospective flatmates and try charm them with your dazzling personality in what feels like a property-based version of Take Me Out.

You also get what you pay for in Berlin. If you’re looking for a bargain, whether that be for your own flat (under $950/month) or a sublet room (under $500/month), expect to live in squat-like conditions with a bathroom that looks like it’s been extracted from a disused gulag. If you opt for the former, be warned: local landlords aren’t obliged to install a kitchen sink, or counter, shelves, an oven, or any other components you usually associate with a house, so you often only get a bare tiled room and the lingering quandary of what you’re supposed to do with a fully-fitted kitchen once you move out.

Nightlife in Berlin truly is incredible of course. The selection of bars and clubs is absolutely unrivaled and the German capital is bathed in a certain hedonistic absolutism that makes for an amazing party, but it also strips it of many of the components that comprise a balanced existence.

The culinary offering, for example, is as poor as you’ll get from a city of this sort of stature, whose restaurants are more befitting of Birmingham than New York. Finding quality meat and fresh fish is a challenge. Infrastructure is shabby. There’s a shortage of ambition. Things are generally sloppier here, more dysfunctional, less professional — scores of little things that don’t register on the dulled senses of someone that spends 60 hours in Berghain every weekend, pickling their brain in GHB.

This might come as a surprise to anyone raised on stories of German efficiency, who envisages the country as some sort of giant, perfectly-automated Mercedes-Benz factory, but Berlin is both a German and European anomaly; and there’s a clear historical subtext as to why things are the way they are.

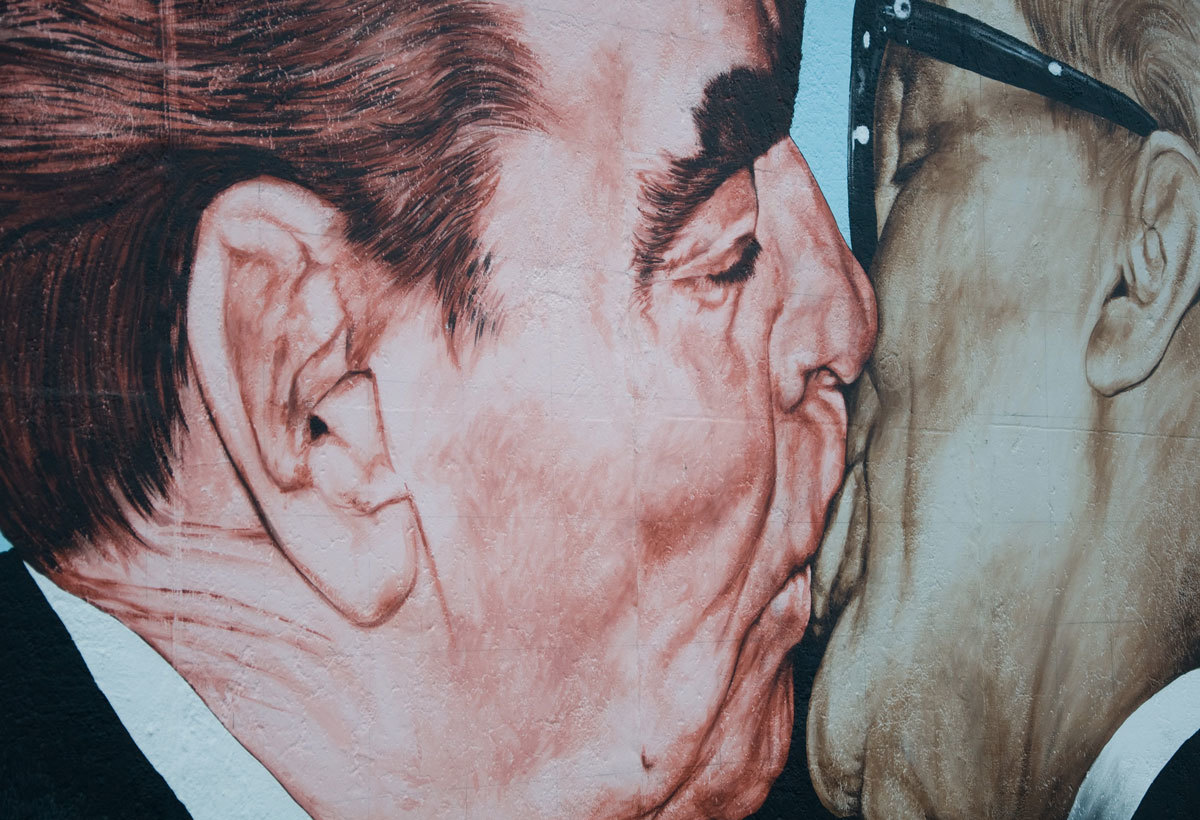

Life here is cheap largely because there’s less money around. Much of the city’s heavy industry was destroyed in the dying days of the Third Reich, leaving it without a manufacturing base to power the sort of post-war economic boom seen throughout the rest of the developed world. The rise of the Wall cut the city off economically as much as it did physically, and the ever-present fear of a communist invasion pushed many major German employers such as Deutsche Bank, Allianz, AEG, Lufthansa and Siemens to relocate their headquarters to the west.

Many smaller ones followed suit, transforming the city into an economic black hole and a blindspot for investors. It would remain in financial limbo all the way up until 1989, by which point companies had invested in so much infrastructure elsewhere that they couldn’t simply move back. This is also why prices here remain low: because there aren’t many bankers, corporate lawyers, or monied white collar types driving the the general cost of living up.

Instead, the German capital has been always been a beacon for dropouts, bohemians, and outsiders. West Berliners were exempt from national service throughout the Cold War, which attracted masses of draft dodgers and others seeking refuge from obligation and responsibility. Conscription and the Iron Curtain might be consigned to history, but this identity remains woven into the fabric of the city, and it’s still a place that people run away to.

Berlin effectively existed outside the clutches of capitalism for nearly 45 years, which has helped insulate it from some of the crueler aspects of the neoliberal agenda. It’s one of those rare places in the first world where you can still be a stylist or run a tech house label without prostituting your weekdays to a job in marketing, even if you’re not particularly good at it. Many come here to escape the market-driven, Darwinian talent contests of London and New York; the absence of financial strangulation gives the great ones a chance to thrive, and provides the mediocre somewhere to hide from their own limitations.

All of these elements swirl together to create a peculiar brand of civilized chaos that has existed in this city since the 1920s, one that has made me see some of the inherent good in capitalism. Somewhere like London, unless you’re a property tycoon or a tory peer, you’re usually on the losing side of the economic equation, which inevitably breeds resentment. I’m freed from that here, so I’ve come to realize that that same financial pressure creates a sense of competition that makes people strive harder, be better, raise their own standards for the purely self-serving purpose of edging ahead.

It’s a big part of the reason why Berlin isn’t a well-oiled, smoothly functioning machine like other Western metropolises, but it’s also why it’s infinitely more humane. I’m not saying that any of this should change — I actively choose to live here for good reason. All I’m saying is that if you’re looking for paradise, this might not be where you find it.

Credits

Text Aleks Eror

Photography N Whitford