Just look at Patrik Ervell’s spring/summer 15 campaign – it consists entirely of vintage photographs by the late Peter Hujar, an artist working during the 80s who was part of the downtown New York art scene. He photographed Candy Darling and Susan Sontag. Ervell’s ads, a collaboration with art director Nick Vogelson, are black-and-white portraits and stills taken (with permission from the owner of his estate of course) from Hujar’s archive – one features a snake coiling around a chair, another a man blocking the sun from his eyes with his hand.

Courtesy Patrik Ervell, Photography Peter Hujar

What does it mean to take another artist’s work and tag it with a brand’s name (in place of the artist’s signature)? “It is kind of a new idea,” said Ervell over the phone. “but you’ve been seeing it for a while on things like Instagram and Tumblr, tongue in cheek images with a Nike logo on it. It’s jarring but very powerful– a scrambling and referencing that’s a part of our modern culture, but it’s applied much more easily to images.” Ervell mentioned Doug Abraham as one such artist, whose account Instagram account bessnyc4 features fashion campaigns spliced with pornographic images, horror movie stills and S&M scenes.

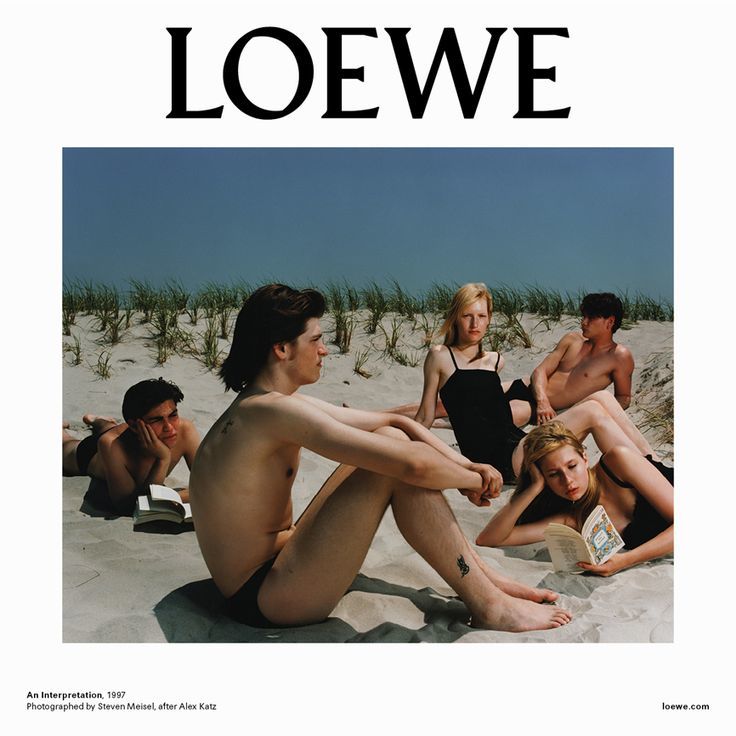

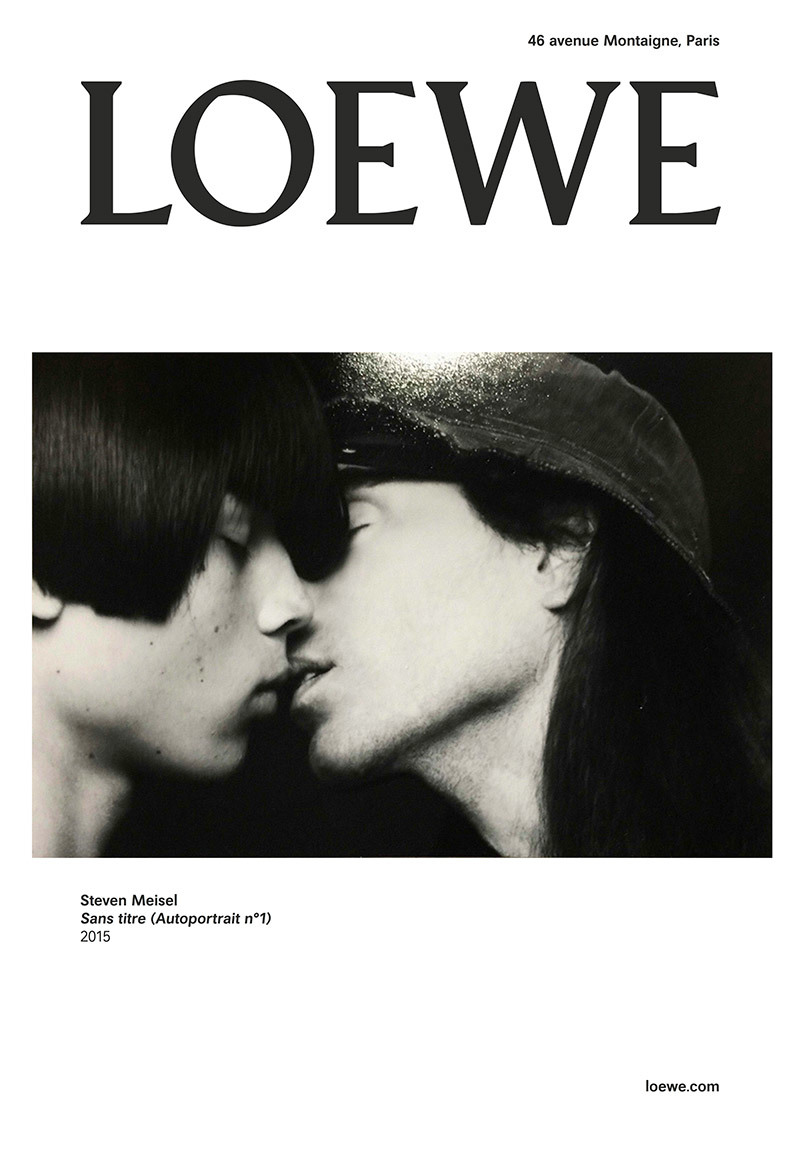

Courtesy Loewe, Photography Stephen Meisel

Like Ervell, British designer J.W. Anderson recently dipped into the archive of a fashion photographer-cum-artist for his first two campaigns with Spanish luxury brand Loewe. For his inaugural fall/winter 14 ad campaign, Anderson used an archival 1997 Vogue Italia spread of Maggie Rizer and Kirsten Owen on the beach, and for spring/summer 15, Anderson selected another archival shot, a proto-selfie of the notoriously shy Meisel locking lips with another man. Opening Ceremony’s spring/summer 15 collection was based entirely on the photo archive of Spike Jonze (not for an ad campaign, but nonetheless still interesting).

Of course, this type of reappropriation is not wholly new. Rei Kawakubo’s Comme des Garcons has been using imagery that has no direct connection with the product as its campaigns for decades. Often creative directed by Ronnie Cooke Newhouse and Stephen Wolstenholme, iconic campaigns have featured work by artist Stephen J. Shannabrook, illustrator Daniel Clowes, and even the Dutch still life painter, Abraham Mignon. And who can forget the pure joy of the 1988 photo of young girls with braces by Inoue Tsuguya and Jim Britt? Like the Ervell ad, these images act on an emotional connection rather than an overt sell.

Courtesy Comme des Garçons, Image Daniel Clowes

Art appropriation has been happening in galleries and museums for longer than Rei Kawakubo has been designing conceptual black dresses. Sherrie Levine re-photographed the work of other photographers, and hung the images in her gallery shows, credited under her name. It was a post-modern critique on artistic commodification. Richard Prince also famously re-photographed a Marlboro ad of cowboys on horses, among other examples. Who owns an image and how close can we get to it? Does it belong to us more if we put our name, or logo, beside it?

And what does it mean for an ad, ostensibly trying to move merchandise, to not include any of the clothes for sale? The marketing strategy is 180 degrees from, say, Apple, who offers pure product on a plain background in many of their ads. But the truth is, Ervell is not trying to sell clothes, he’s trying to sell a brand. “We’re not a giant machine that needs to churn out product. My customer is coming to me for my brand and they already know the brand. For me it makes a lot of sense,” said Ervell. Re-appropriating a work of art comes with a battery of built-in references; it’s the most direct, stream-lined way for a new brand to connect with a history.

For Ervell, that history is a dark, but romantic vision of the 1980s New York City that orbited around Andy Warhol. Ervell chose never-before-seen photos from Hujar’s archives, so it’s also an intimate glimpse into the mind of a gay photographer who died tragically young.

Courtesy Comme des Garçons

Sure, some of this can be pegged to fashion’s current strand of nostalgia. Legendary models from the past like Kirsten Owen and Maggie Rizer are fetishized and promoted by young photographers and designers, so it would make sense to revere old pictures of them. Older fashion photographers are continually being rediscovered and re-integrated into the fashion scene. Just look at the new ascendence of 70s superstars Hans Feurer and Walter Pfeiffer. Young fashion fans have made an art out of curating vintage fashion images on Tumblr and Pinterest.

But this trend can also be attributed to fashion’s unique ability to sell a lifestyle rather than a product. We buy into the person we want to be, not the items we want to own.

Patrik Ervell and Jonathan Anderson are similar in many ways–both highly intelligent young designers who produced collections this season that looked simultaneously backwards and forwards. Anderson’s eponymous menswear show for fall took place on purple rubber with show notes that envisioned the customer as a “free-spirited thinker with an interest in pataphysics.” For Ervell it had more to do with innovative fabrics, inspired by science fiction and Brutalist architecture. Best to explain their retro-futuristic visions to the public with new photographs from old photographers. “All of those images are kind of timeless,” Ervell said. “If someone told me they were taken last week I would have believed them.”

Courtesy Comme des Garçons

Credits

Text Austen Leah Rosenfeld