We’re entering a new era for Lana Del Rey. Her first three major label albums, Born to Die, Ultraviolence, and Honeymoon were complicated, enigmatic, and divisive records that illustrated an artist stitching together a character for themselves. Someone who could, perhaps, act as a front between the often fatalistic and nihilistic content of her music and the woman behind that breathy and classic voice.

It was never clear throughout all her iterations — May Jailer, Lizzie Grant, her real name, or Lana Del Rey — whether what we were seeing was actually what we were getting. After the initial buzz around her proper debut, “Video Games,” the (predictably misogynistic) search for authenticity about who Lana was — rich heiress or femme fatale? — left many scratching their heads. Could someone really inhabit a world built upon the melancholia of a Tennessee Williams play, the glamour of Jackie Kennedy, and the hazy darkness of a Harmony Korine movie? This quest for answers has, both positively and negatively, impacted one of today’s pop music success stories

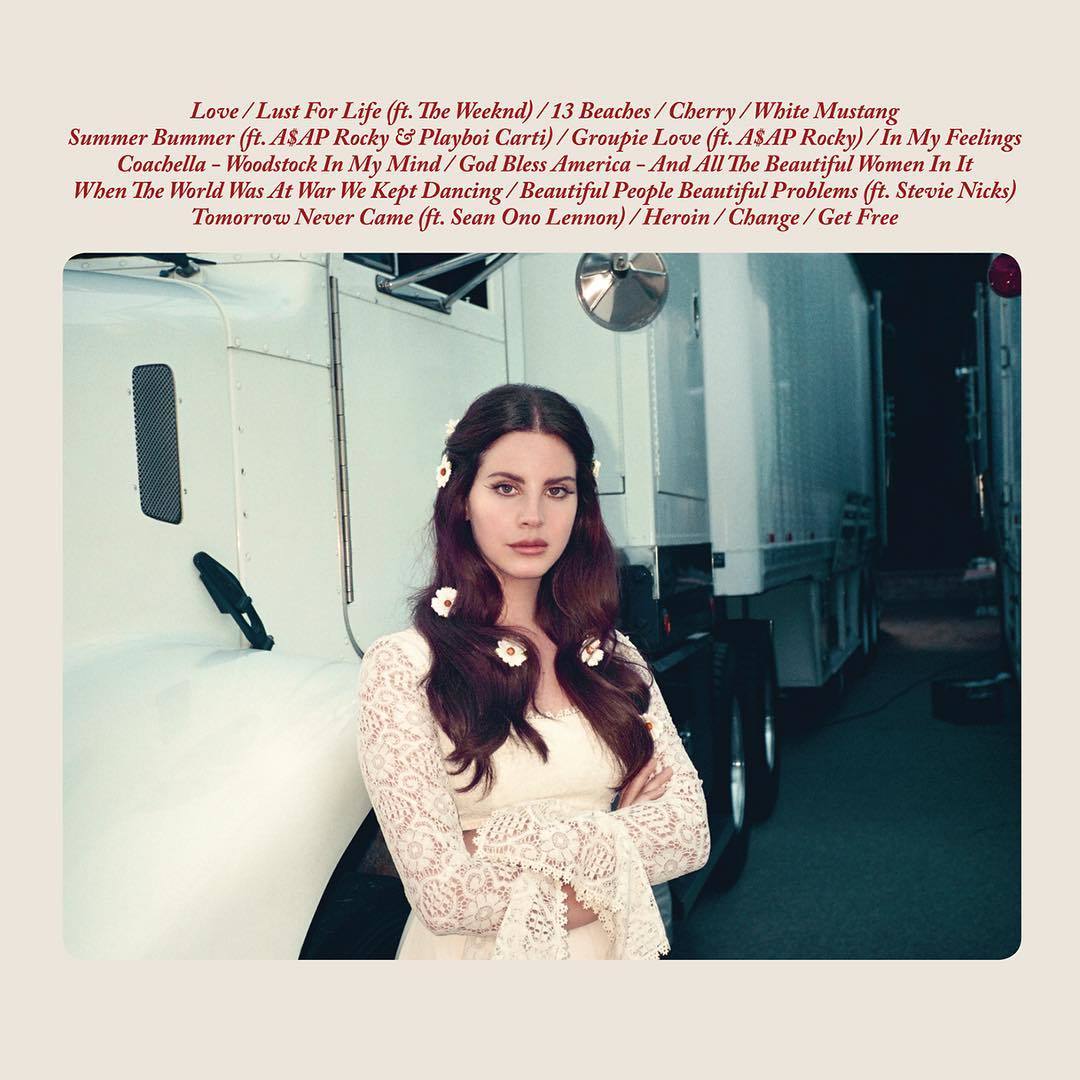

So when the optimistically cinematic lead single “Love,” and the Lust for Life cover art (an image of a beaming Lana with flowers in her hair) were unveiled, again it was debatable whether this was where Lana Del Rey was really at or if it all was playacting.

Yet, upon listening to Lust for Life, something becomes apparent: five albums in and the veneer and character might be peeling back.

Speaking to Zane Lowe on Beats 1, Lana expressed that things had become less insular for her. “I like to think of it almost like I’m looking, finally, from the inside out, rather than being, like, on the outside not connecting as much,” she said. “I think it just takes time to adjust to everything, integrate everything — to be a singer and be a fan of other people — and have the whole thing work.”

This observational approach to her music doesn’t mean that the singer has dismissed her ennui. In fact, Lust for Life could be the most Lana Del Rey album yet. Across 16 tracks, the hybridity of hip hop, jazz, and 60s nostalgia is still omnipresent, but the personal nihilism and devastating storytelling has turned slightly towards the light. Likewise, her fetishized idea of America has been put on blast.

While there’s optimism about the future on “Love,” Lana questions society writ-large, albeit without necessarily being didactic. The fine line between parody and the political on “Coachella — Woodstock In My Mind” and “God Bless America — And All the Beautiful Women In It,” complete with gunshot production, see the singer push outward, absorbing some of the Western world’s current trauma.

These wryly delivered observations, however, are matched against the soft rallying cry of “When the World Was At War We Kept Dancing,” a song described by producer Rick Nowels as a “masterpiece.” In the age of post-truths and pussy grabbing, Lana pointedly asks whether we’ve finally come to “the end of America” as we know it. Yet, whereas before he may have luxuriated in desolation, there’s a thoughtful rebuttal: “If we hold on to hope, we’ll have a happy ending.”

Lana Del Rey may no longer be swimming in the marshes of total misery, but she’s still meditative on her experiences — and now the experiences of the world, too. “We spend a lot of time when the nation was founding building government, money, and then getting the education system down, so it’s not like some cultures where you take time to mediate, et cetera, on your own dreams, wishes, self-worth,” she said to Flaunt magazine. “I think it’s not enough practice. It’s not like they teach you that in school. But I think that that’s changing too. That’s actually a lot of what the record is about.”

Like with Sia’s 10,000 Forms of Fear, Beyoncé’s Lemonade, or even Janet Jackson’s Velvet Rope, with Lust for Life Lana has reached a creative zenith by undertaking a journey of personal discovery and growth.

If Born to Die, Ultraviolence, and Honeymoon were the foundations, then Lust for Life is this newfound realization that takes all aspects of someone’s life into consideration. How do you co-exist with both your personal, public, and political trauma? Across a lengthy 16 tracks and 71 minutes, the answer to this question is not answered, but traversed.

The trinity of songs “13 Beaches,” “Cherry,” and “White Mustang,” explore stalwart themes of isolation, celebrity, and dangerous love that we’re used to from the singer, but are delivered with more surety. Whereas before there was some resignation in the music, like with “Terrance Loves You” and “Ride,” here there’s a self-described annoyance that, unfortunately, she’s still feeling this way. That this emotional ebb and flow is still a part of her life, however, comes with its own realization, and on “Groupie Love” she acknowledges and leans into the predictable adoration of bad boy rockstars and fucked up love affairs.

The wry and sardonic quality to songs like “Fucked My Way Up To The Top” and “High By The Beach” also still litters through Lust for Life, and on the Stevie Nicks duet “Beautiful People Beautiful Problems” — a song that producer Nowels described as having “two of the great female poets of songwriting” come together. Both singers embrace the ridiculousness of its title. “Working on your song has changed me forever because I’ve learned from you,” Stevie Nicks recalled in a conversation with V Magazine. “We are witchy sisters and that’s it. That’s where “Beautiful People, Beautiful Problems” comes from, because we are trying to ride above all the problems and have hope in everything else, but it’s still a world filled with problems no matter how hard we try to change it.”

Likewise, “Heroin,” while sonically melancholic, is an ode to the hazy California of the past, with tongue-in-cheek references to her internal darkness and nihilism through the Charles Manson murders and hedonistic heavy metal group Mötley Crüe. Ultimately though it all twists when, at the end of chorus she sings, “I’d be lying if I said I wasn’t sick of it.”

A recent interview with Pitchfork appeared to show an artist who was figuring it all out. Referring to the devastating ballad “Black Beauty” from Ultraviolence, Lana began to cry. That song details how the bleak darkness of a partner infected her own world outlook. “I was connected to that feeling of only being able to see a portion of the world in color. And when you feel that way, you can feel trapped,” she said, explaining her tears.” When asked how she was feeling now, all she could say was that she didn’t know.

Listening to a song like “Change,” which was recorded just a day before the album was meant to be delivered to the record label, it’s clear that Lana is realising that it’s okay to not understand how you’re feeling — and how that in itself is empowering. “Change is a powerful thing, people are powerful beings/ Trying to find the power in me to be faithful,” she sings. “Change is a powerful thing, I feel it coming in me/ Maybe by the time something is done/ I’ll be able to be honest, capable.” Like many who were awoken after the shocking result of last November’s election and the shifting conservatism in politics, Lana is aware that she could be doing more. But this realization is also a personal one, as she sings, “When I don’t feel beautiful or stable/ Maybe it’s enough to just be where we are.”

Like with Sia’s 10,000 Forms of Fear, Beyoncé’s Lemonade, or even Janet Jackson’s Velvet Rope, with Lust for Life Lana has reached a creative zenith by undertaking a journey of personal discovery and growth. However, unlike those records, hers has been one that involved widening her world view so she can begin to understand that change, both personal and political, comes from within. That doesn’t mean that she’s reached absolution, and speaking to Zane Lowe about the omission of previously hyped tracks Yosemite and Architecture from the Lust for Life tracklisting, Lana admits that they were just too happy. “I think I thought by the end of [making] this record I’d be in a totally different spot. Like a little bit of a 180,” she said. “And then I realized that I’m still figuring out so much stuff.”

It’s a revelation that’s apparent on album closer “Get Free,” and one that truly exhibits why Lust for Life is Lana Del Rey’s most important work to date. On top of marching percussion, she acknowledges that in order to progress she needs to take “the dead out of the sea, and the darkness from the arts.” For an artist whose career has been built upon the wretchedness of the human heart and the glorification of the decay of society, it’s an inexplicably emotional shift that, across the album and its creation, has been stalked, argued with, and battled. And while she doesn’t necessarily offer any answers for how to achieve this emancipation, the realization is itself enough. “I never really noticed that I had to decide/To play someone’s game or live my own life,” she sings. “And now I do.”

Credits

Text Alim Kheraj