Did you know that the first nose job to go publicly wrong was in the early 1900s? Back then rhinoplasty was fairly basic. Liquid paraffin wax was injected into the nose and then molded into shape until it set solid. The case in question involved Gladys Deacon – a renowned beauty and Brit aristocrat – and the wax slipped down into her chin causing a facial deformity that reportedly turned her into a recluse and her home into a mirror-free zone.

In the sixties, American plastic surgeons started to get good at boob jobs and other implants and by the 1980s women were undergoing major “works” from full facelifts to chin implants. As women burst through the glass ceiling they appropriated their bodies and surgery was one way of giving nature and the aging process the finger.

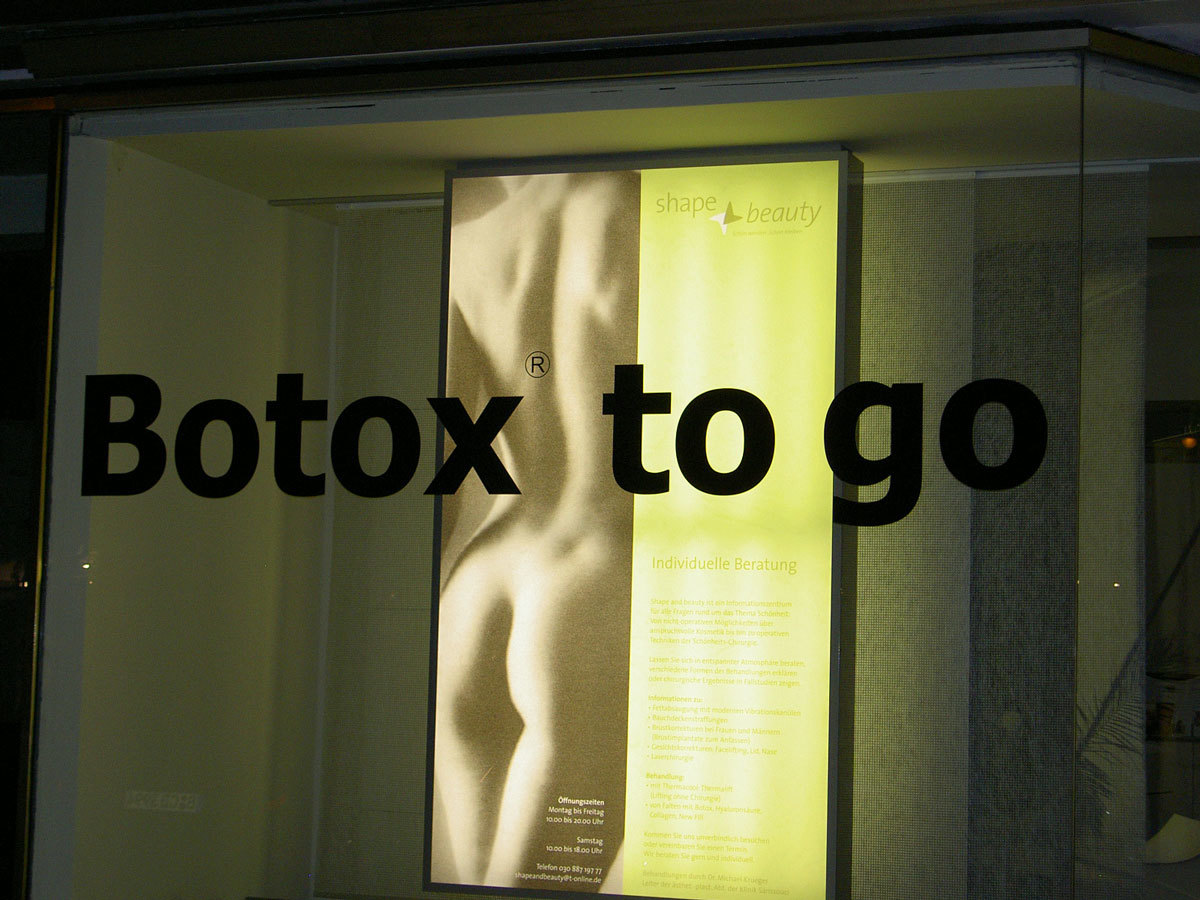

The latest stats on surgery show that things are getting subtler. The figures from BAAPS (The British Association of Aesthetic Plastic Surgeons) at the start of this year revealed that larger scale ops like tummy tucks and nose jobs are on the decline but that smaller, less invasive ‘tweaks’ are growing in popularity fast. In fact, inquiries into non-surgical cosmetic treatments in the UK rose by more than half in the last six months according to data from WhatClinic.com. Demand for dermal fillers are up by 61% and thread lifts (non-surgical facelifts) are the fastest growing procedure in the same time period.

For us gen-Y-ers and millennials, this is how it’s done. Hindsight has allowed us to witness the surgery faux pas of the generations before us. Memories of Jocelyn Wildenstein alongside current Instagram images of Kim Kardashian wannabe Jordan James Parke haunt those of us young enough not to have felt the full extent of wrinkles. Cosmetic procedures have got better and safer so it makes sense that smaller, less invasive procedures are on the rise in what can be described as a “little by little” approach to self-improvement. These smaller flections are harder to spot and easier to deny. Lately the “did they didn’t they?” debate of the media has eeked out reluctant confessions from musicians to models to social media stars, and the result is a gradual transmutation into: the same face.

Rapidly gaining popularity in elite circles are vitamin injections and volume replacement treatments (using hyaluronic acid) – both of which are the kind of minor tweaks that make you wonder whether the person in question is doing 90s lip liner or trialling out a new more flattering, more permanent social filter. According to former BAAPS President Rajiv Grover, tip rhinoplasty is also increasingly common in young models and fledgling actresses who rely on looking good in front of a camera. “As opposed to a full nose job, this is where the fleshy bit at the end of the nose (the part than can be an issue photographically) is altered and refined. They look more beautiful in real life as a result but the main reason they do it is for photography.”

Make-up artist Kay Montano says that Marilyn Monroe (who had her nose surgically ‘buttoned’ along with chin implants for better jaw definition) has a lot to answer for. “Monroe created the most well-known facial archetype that seems to have stuck. If you look at her features, you’ll see that a lot of ‘recreated’ faces mirror hers. It is a childlike beauty; women suspended as girls. It is as cute as it is un-threatening and I’m pretty certain that this archetype gets hardwired very early into our subconscious, especially as the exaggerated version of these features (baby nose and faux innocent pout) is the face of the dolls we grow up with too.”

Depressingly, the trend for “normalization” has meant that cosmetic procedures have become the new beauty maintenance, as unusual as going for a facial or having your bikini line lasered. In South Korea the culture has become even more warped (in fact going full circle back to the extreme), where mothers are treating their teenage daughters to jaw shaving ops and double eyelid surgery. “It seems to have become popular around the world to consider these treatments as a commodity” says Grover, “but unfortunately when you’ve had an operation like this you can’t take it back to the shop.”

Social media and the rise of the selfie-obsessed culture have obviously fanned the flames. The media presents us with these tiny alterations via millions of images every day and of course we absorb it. Subconsciously, it makes sense that we start to acknowledge the tweaks as the norm, mentally transferring the very same adjustments onto our own faces every time we ping out a selfie (and feeling bad about ourselves when the image doesn’t match up). Apps like Facetune and Perfect 365 groom us for the reality of future nips and tucks, allowing us to fiddle with our bone structure and complexion, unbeknownst to our followers, and gaining approval of this normcore version of beauty via a stream of likes.

This slow eradication of diversity from beauty seems a depressing and soulless eventuality. You can’t help but feel that one day the wind will change and we’ll be stuck living in a world of plastic clones with identical pouts and pillowed cheeks – akin to the generation that over-plucked their eyebrows and could never grow them back. In the meantime those of us who look different (famous or not) need to be celebrated, not modified. There is some good news: tweak all you like but no amount of cosmetic surgery will ever change our genetics and, until the frightening time when we have the scientific ability to predetermine the shape of our offspring’s noses, Mother Nature will have the upper hand.

Credits

Text Katie Service

Photography Axel Hecht