When Issei Suda was asked about his shooting process, he said simply: “I’ll photograph anything I think is good.” It’s an uncommonly simple goal, but one that helps to explain the quiet grace of his work. Issei is without a doubt one of Japan’s finest; however, up until his death in 2019, he remained almost anonymous in the west. This might be because he feared “causing agitation or expressing political dissatisfaction,” and so didn’t align himself with the militant motives that consumed his contemporaries — or any movements for that matter. If any, it would be surrealism, as Giorgio de Chirico was Issei’s favourite artist, although the photographer resisted any direct influence. “I prefer to discover small surprises that are usually dismissed in our world,” Issei said. “Surreal things are not only within my work but all around us.”

To understand Issei, you have to go back to his roots. In 1967, after completing a course at photography school (despite his father’s wish for him, as the only son, to carry on the family’s small business), Issei was recruited as a stage photographer for the audacious underground theatre troupe Tenjô Sajiki. It was led by Shūji Terayama, a cultural outlaw whose wild and frightening reinventions of indigenous Japanese mythology made him a provocative public figure of the lively avant-garde scene in the 60s. Mixing themes of folklore, rural superstition, dreams and magic with highly dramatic music, lighting, vulgar imagery, and black comedy, Shūji’s style sat in stark contrast to Issei’s more subdued sensibility. However, Shūji’s influence on Issei was tremendous, inspiring him to seek out two things. One: the “essence” of a pre-modern Japan. Two: the innate creativity of the common person.

In 1971, Issei said he was “at the start line, ready to go.” Setting forth as an independent, self-guided photographer, he travelled through the Japanese countryside — the last vestige of an old, discarded world — shooting down-to-earth rural folk engaged in matsuri (festivals). Witnessing this “collective madness” was, for Issei, “a deeply emotional affair.” He compiled his performative shots in Fushi Kaden (1978), a now-mythical photobook. It borrows its name from a classic 14th-century treatise on Nō theatre (a traditional Japanese theatrical form) translating to Transmission of the Flower of Acting Style, written by Zeami, considered the greatest playwright and theorist of Nō theatre. Issei read it “avidly”, and his pinching of the title declared his intentions to capture the actor’s hana (flower) – that is, a transcendent state in which one can find the universal in the individual.

Despite his interest in native Japanese tradition, Issei was not the nostalgic kind. “I can observe things objectively without getting deeply involved,” he once said, adding: “This can be quite fun because I can construct my own drama in my head.” It wasn’t long before Issei brought his unique brand of theatrical photography to the streets of Tokyo. Issei did not make the city his muse as Daido Moriyama did, but he made it his stage.

Issei’s archive is the gift that keeps on giving, as evidenced by a handsome new clothbound book released by Akio Nagasawa Publishing, entitled The Sketch of Kanto Area. It compiles the little-known city snapshots he published across six issues of Asahi Camera magazine in 1983. As in the originals, the chapters are subtitled with Japanese pop song titles. Indeed, there’s a distinctive musical quality to Issei’s shots. Capturing whatever was spontaneous or mysterious, he could photograph almost anything and make it sing.

The foreword finds Issei dwelling on the confusions of city life. “Here I am, drinking High Sour and spluttering arguments in the middle of a downtown street, trying to forget the pain when my heart feels empty, and dreaming of Madonna, as I take my ‘Tokyo chika chika syndrome’ with just a little sigh. And I’m going to laugh at things again tomorrow… I will only hear myself muttering: ‘What a great city Tokyo is!'”

The little alleyways Issei wandered — seemingly worlds away from the urban sprawl of the metropolis — were like towns-within-towns. While you’re only ever privy to small glimpses of the city’s architecture, over the course of the book, an enchanted atmosphere emerges, infused with the lingering mysteries of an understated drama. “Instead of stars that I used to see in the sky, the night is filled with stars of neon that glitter suspiciously like beckoning light traps,” Issei wrote. “From down in the valleys between buildings, the looming peaks of black concrete form sceneries that almost feel sublime to me.”

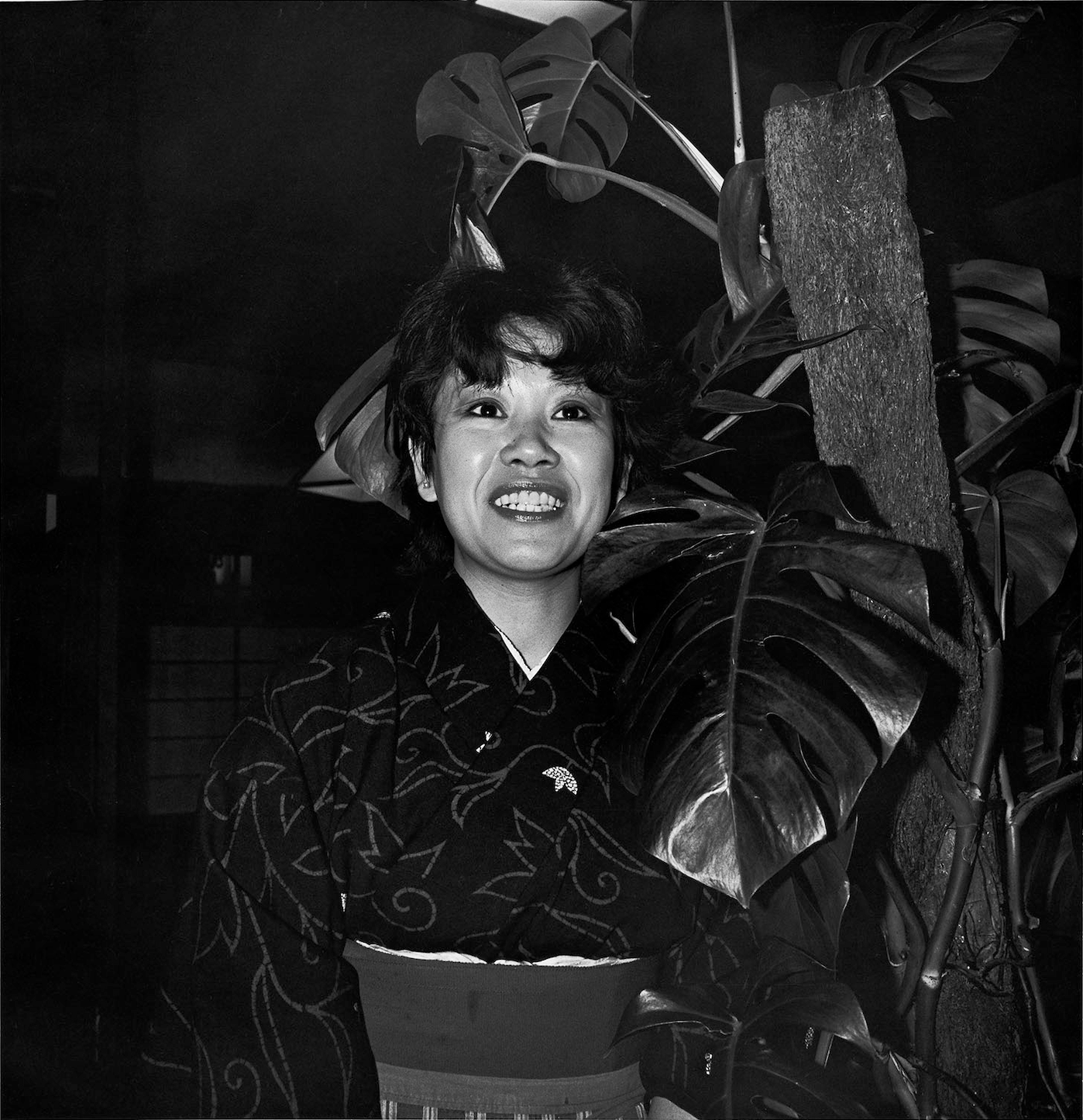

Despite Issei’s refusal to make any grand social or political statements (the 80s saw a giant bubble economy propel Japan to new heights of extravagance and excess), he was witnessing more evidence of modern living. Each frame uncovers its own dissonant harmonies and puzzling nuances, with the textures of western modernity and traditional culture not so much clashing as intersecting. A businessman in an oversized suit crosses a thicket of bamboo. A dainty schoolkid skips under colossal steel girders. A kimono-clad girl slurps a beer in hip urban style (she’s obviously a different kind of woman to those Issei saw in the countryside). Even in the small corners Issei inhabited, change was afoot.

While these photographs are rich in references — the pan focus of Orson Welles, the sharp contrasts of Richard Avedon, the inky figures that might have even made his mentor Shūji shudder with delight — Issei’s POV is unmistakably his. The technical precision he found within the square format is unrivalled, and totally at odds with the savagely abstracted “are-bure-boke” style (translating as “rough, blurred and out-of-focus”) that had revolutionised Japanese photography in the 70s. But this isn’t to say that Issei was after the “perfect” shot. Working carefully yet instinctively, Issei saw himself as a channeller of the chaotic forces of the universe. “There is always a crazy idea or two flying around,” he said. “They will surely come to my mind and lift me up.”

This spontaneous (he said “reflexive”) way of working is what gives Issei’s pictures a peculiar subjectivity, which rubs up against the surreal. Time and time again, you get the sense of Issei holding on for too long, transforming an ordinary scene into something half-a-click off-centre. Subjects are caught unprepared — eyes blinking, hair blowing, head hunching — suggesting the cultural setup has been breached. While the slip of a girl’s plastic smile into a less than cooperative scowl might be an awkward mistake in timing, what Issei reveals is something universal about the human subconscious.

Issei’s photographs do not pulsate with the self-questing delirium of his Provoke contemporaries — the radical Japanese photo magazine printed in the late 1960s — (think Daido or Takuma Nakahira). Nor will you find in them the brash passion of politics, seduction, youthful rebellion or social critique. Bypassing the swagger and machismo that marked his generation, Issei crafted his own observant aesthetic that made space for sensitivity and vulnerability. His enduring legacy is in the very tender ways he gave expression to the underlying mystery of daily existence.

“Just like there exists no flower that has no name, there are no nameless humans existing in reality,” Issei once wrote. “While seemingly buried in the casualness of daily life, all of them carry their own individual power and toughness, concealed deep within… Their time may have been just a passing moment that is long gone, but as a photographer, I seem to feel the repercussions and the significance of their existence still today.”

‘The Sketch of Kanto Area‘ by Issei Suda is published by Akio Nagasawa Publishing.

Credits

All images courtesy of Akio Nagasawa Publishing