If you’ve inhaled all of Blue Planet and Planet Earth, you’ll know that animals are phenomenally intelligent beings that would probably do a better job of running the world than certain humans. That until we came and shoved our snare traps and plastic into the mix, animals had everything balanced in a complex but complementary series of ecosystems that held together like a caramel-bound croquembouche.

But we came, we saw, we poached. And now some people are trying to undo years of screwing up the system and rendering species endangered or extinct — while trying to prevent even more damage being done. Enter The World Land Trust, a charity working to protect threatened animals and habitats. Together with fashion photographer and i-D regular Jamie Hawkesworth, and The Wildlife Trust of India, they’ve released a book — A Study of Human and Animal Habitats — documenting elephants in India and their often contradictory relationship with the humans surrounding them. Because while humans have a big part to play in the creatures’ decreasing numbers, the current dynamic is not so simple. We should also mention now that all the proceeds from the book sales will go towards WLT and WTI’s wildlife conservation efforts in India, so it’s a much better investment than that pair of socks with tiny Minions on them you bookmarked for Dad.

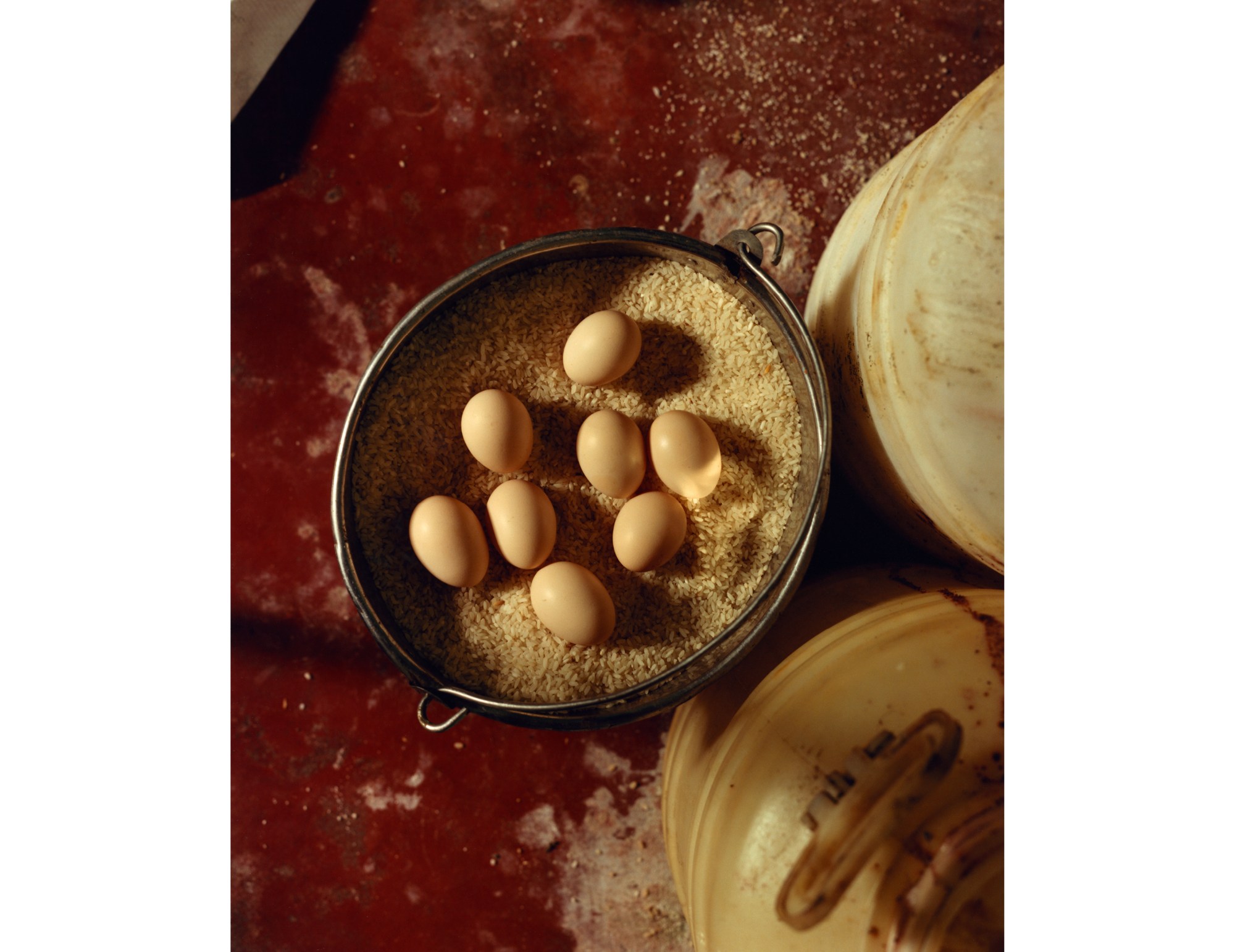

In India, elephants have an entrenched cultural importance through many years of portrayal in folklore, painting and literature. But while greatly revered, they’re also feared — around 400 hundred people are killed by elephants in India each year. Alarm about being trampled by them means elephants are often poisoned or trapped and killed. On top of this, poaching is on the rise again, and human activity is encroaching on their natural habitat. The Wayanad Elephant Corridor — where all the photos for the book were shot — is a small but integral piece of land for wild animals, bridging two national parks they migrate between to find food and mating partners. But the growing presence of humans has seen this open space shrinking, leading to a tense fight for space and more deaths on both sides.

But, like any relationship, it’s never straightforward or one sided, and the book isn’t out to demonise humans — we’re not all bad. As its creative director Jonny Lu says, “In Wayanad we met Mahout, an elderly man who slept with orphaned baby elephants, in an attempt to comfort them throughout the night as they missed their mothers. We met rangers who stayed out all night in the rain, in leech infested swamps (which, we can confirm from first hand experience are as bad as they sound), to collect data about migrating elephants. We met an older woman, who had been living in the forest for 70 years, who described the elephants and tigers that used to pass by as her “children”. Local people have a clear and unshakable love and respect for the elephants and the natural world; a deep spiritual connection that spans generations.” But again, it’s twofold, with Wu continuing, “Contrary to this we also heard of an elephant in a nearby village that had been poisoned, and graffitied with the name Bin Laden; killed for its ‘habitual crop-raiding’ forced upon it by starvation.”

The images in the book give an astounding insight into the area, and the conflicting and turbulent relationship between humans and wildlife. So rustle up the stash of coins you have lurking in the swear jar and down the back of the heater, put away your gift lists, and buy ma and pa — and yourself — something that does some good this Christmas. In the words of Sir David Attenborough, Patron of the World Land Trust and all things good in the animal kingdom, “The money that is given to the World Land Trust, in my estimation, has more effect on the wild world than almost anything I can think of.”